Search Posts

Recent Posts

- A crack in the foundation – Michael Morse June 8, 2025

- Ask Chef Walter: Ultra processed foods – Chef Walter Potenza June 8, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 9, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 8, 2025

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Providence Reparations announcement part of international agenda

A press conference was held yesterday in Providence as the city’s mayor, Mayor Jorge Elorza, announced a program intending Providence to be the first city to consider reparations for Black and Indigenous people. In fact, Providence’s efforts were just one of several happening in the US and internationally in the last few weeks.

Elorza signed an Executive Order committing the city to a process of truth, reconciliation and municipal reparations for Black, Indigenous People, and People of Color in Providence.

In addition to the mayor, City Councilwoman Nirva LaFortune, 1696 Heritage Group Vice President Keith Stokes, Founder and CEO of Impact RI Janice Faulkner, Community Relations Advisor Shawndell Burney-Speaks spoke.

“As a country and a community, we owe a debt to our Black, Indigenous People, and People of Color, and on the local level, we are using this opportunity to correct a wrong,” said Mayor Jorge Elorza. “Though this does not undo history it is the first step in accepting the role Providence and Rhode Island has held in generations of pain and violence against these residents, healing some of the deepest wounds our country faces today. May this process of truth bring us education and awareness of these wrong-doings and may our reconciliation change the systems that continue to oppress our communities, while reaffirming our commitment to building a brighter, more inclusive future.”

The social justice undertaking is designed in three parts. The collection of truth. The process of reconciliation. And, reparations.

“Providence can lead the nation on how we present the inclusive history of all Americans through public memorials, public investments and public education,” said 1696 Heritage Group Vice President Keith Stokes. “The truth-telling that begins today through the Mayor’s vision will not only validate our earned African heritage and history in Providence, but also that of Black Lives Matter and Black History Matters, too.”

Sue Cienki, Chairwoman of the RI Republican party said she thought the idea of reparations “which I think is an absurd idea for a city on the brink of bankruptcy, with many unfunded pension liabilities in the billions of dollars”. Cienki said the way to provide help with Black Lives Matter is to educate children in the schools.

According to the Mayor’s press release, “this process was developed with and crafted by the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the administration. Those interested in engaging in the subcommittees of the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group are encouraged to contact Community Relations Advisor Shawndell Burney-Speaks at sburneyspeaks@providenceri.gov.

Meanwhile, in Ashville, North Carolina

Ashville, North Carolina also announced their reparation program yesterday – with their City Council leading the effort. The City Council voted to apologize for the city’s historic role in slavery, discrimination and denial of basic liberties to Black residents and voted to provide reparations that will benefit them and their descendants. The resolution does not mandate direct payments, but instead calls for investments in areas where Black residents face disparities, including boosting minority home ownership and access to other affordable housing, increasing minority business ownership and career opportunities, developing strategies to grow generational wealth and closing the gaps in health care, education, employment and pay. Read the resolution, page 4, here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KNSoINXMd7eJJQ7al897hgIz__WV955C/view

In London, England:

Under the mantra that it is ‘not enough to say sorry’, British firms should pay reparations for slave trade, say Caribbean nations, as the Lloyd’s of London insurance market apologized for its “shameful” role in the 18th-century Atlantic slave trade and pledged to fund opportunities for black and ethnic minority people. A Caribbean business alliance of 12 countries – including Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados – said leading British institutions should take part in a “negotiated settlement” to give some wealth back to the Caribbean. It was sugggested that British institutions sit down with Caribbean nations to fund development projects or consider something similar to the Marshall Plan – a reference to the US aid given to Europe after the destruction of World War Two.

In Durham, North Carolina

A reparations program in Durham should include economic investment in Black communities along with state and federal resources, and the city should focus on opening up the Black business pipeline. It should increase the diversity of places where Black businesses are established, so that they can capture diverse dollars while also taking advantage of the redevelopment of historic Black commercial and residential corridors. It should increase access to the capital needed for the Black business ecosystem to grow.

In short, the city should remove as many barriers to success as possible for Black entrepreneurs, while also investing in education to expose more Black youth to innovative environments. This might entail committing public properties to create Black wealth, with a focus on community improvement without forced displacement. It might entail the creation of a real-estate bank for intentional, inclusive development. It might entail finding creative ways to get the private sector in Durham to invest at a large, long-term scale.

“While the fight for reparations is happening, can we prepare the infrastructure of Black businesses,” he says. “Perhaps if Durham can lead the way and get it right, then cities all across America will follow suit.”

Evanston, Illinois

One city’s reparations program that could offer a blueprint for the nation is Evanston, Illinois. They are levying a tax on newly legalized cannabis sales to fund projects benefiting African Americans in recognition of the enduring effects of slavery and the war on drugs. 100% of the tax will go to the fund which may begin allocating funds this year in “hopes to prioritize housing initiatives aimed at addressing the impact of redlining on the suburb’s black community, as well as programs related to education, employment and healthcare”.

Chicago, Illinois

The City Council adopted unanimously the formation of a reparations study committee, only to overturn it two weeks later. It will now be an annual report that the council must issue and the council voted they “will work to right the wrongs of the past in order to overcome the many obstacles to employment, education, housing, justice, due process, health care and more facing African Americans.”

Elsewhere

Other cities have been researching and discussing the issue of reparations for years – some even acknowledging they will do something – but no monetary action occurred. Others have called for efforts to take place at the federal level, and some have suggested the government develop a statute of limitations for reparations against any group of people for wrong-doings.

Internationally

Europe, the Caribbean, Haiti, and African nations have discussed reparations in policy and monetary amounts for decades.

Nationally

Legislation to provide reparations has been working its way through the US Congress for over 30 years. Black Lives Matter and the death of George Floyd have brought the legislation to the forefront again. If passed, there would be a study to determine what the federal government owes the descendants of slaves, and explore ways to repay that debt.

H.R. 40, merely a mandate to study the idea of reparations, has languished without a vote for decades. And while increased awareness and a demand for active steps may bring the bill out this year, the severe budget problems brought on by COVID19 would limit the billions estimated to go along with any equitable resolution.

Recently, the Conference of Mayors has endorsed action on reparations. at the city level as well.

Rhode Island African Heritage and History Timeline: 17th through 19th Centuries

Keith Stokes provided this timeline and reviewed historical facts at the event. As Stokes is known to say, as Black Lives Matter, Black History Matters:

1636 Providence settlement is established

1639 Newport settlement is established on southern end of Aquidneck Island.

1640 Dr. John Clarke grants land to the Town of Newport to establish a Common Burying Ground for all residents regardless of race, creed and class.

1652 Colony of Rhode Island adopts a law abolishing African slavery, where “black mankinde” cannot be indentured more than ten years. The law is largely unenforced.

1660 Charles II, King of England orders the Council of Foreign Plantations to devise strategies for converting slaves and servants to Christianity.

1660 – 1730 Narragansett’s largest land-owning planters include Updike, Hazard, Champlin, Robinson and Stanton that own at least 1,000 acres. By 1730, enslaved Africans represent about 15% of areas total population.

1663 On July 8th, King Charles II grants the Colony of Rhode Island a Charter that guarantees religious toleration.

1676 As a direct outcome of the King Phillip’s War (1675-1676), surviving Natives are enslaved in Rhode Island.

1680 According to the colonial census, there were 175 Native and Negro slaves in Rhode Island.

1683 On March 30th, Negro servant Salmardore is emancipated by his master John Champlin in Newport.

1696 The first documented slave ship the Boston bound, “Sea Flower” arrives in Newport.

A Negro named Peter Pylatt was executed at Newport for the crime of rape, after which his body was hung in chains on Miantonomi Hill.

1703 Rhode Island General Assembly adopts an early “Negro Code” to restrict activities of free and servant Negros and Indians stating, “If any negroes or Indians either freemen, servants, or slaves, do walk in the street of the town of Newport, or any other town in this Colony, after nine of the clock of night, without certificate from their masters, or some English person of said family with, or some lawful excuse for the same, that it shall be lawful for any person to take them up and deliver them to a Constable.”

1705 A Negro burying section of the Common Burying Ground is established. It is later known to the African American community as “God’s Little Acre.”

1708 Enslaved Africans outnumber indentured white servants in Newport 10:1

1709 A duty of three pounds was placed on every Negro imported into the colony.

1709 – 1809 Rhode Island merchants sponsored nearly 1,000 slaving voyages to the coast of Africa and carried over 100,000 slaves to the New World. Before the American Revolution, Newport was the leading slave port and after would be Bristol. Rhode Island’s slave traders transported more slaves than the other British North American colonies combined during the 18th century.

1713 Rhode Island merchants introduced rum on the African coast; the “new” liquor quickly becomes a chief source for trade of slaves.

1714 Colony of Rhode Island enacts a law that bans any ferryman from transporting a slave “without a certificate in their hand from their master or mistress or some person in authority.”

1715 The General Assembly of Rhode Island officially authorizes African enslavement by requiring a listing of imported slaves and a per head fee payment to the Naval Officer upon arrival.

1725 In Warwick, Rhode Island on July 28, 1725, Hager, a “negro” slave, was willed 10 shillings and her children were bequeathed 5 shillings each by Captain Peter Green.

1739 Venture Smith who was born Broteer Furro from Guinea is brought to Newport as a 10 year old slave boy. He would later as a free man author, “Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America, Related by Himself.”

1741-1763 Several of Newport’s most important civic structures, Old Colony House, Redwood Library, Brick Market and Touro Synagogue are built with the participation of enslaved and free African skilled labor.

1743 The Reverend Honyman of Newport Trinity Church in a June 1743 letter reports that his church is in very flourishing and improving condition, “there are in it a very large proportion of white people and one hundred Negroes who constantly attend the worship of God.”

The Reverend James McSparren of Narragansett’s St. Paul’s Church noted that “70 slaves and Indians were members of his church.

1750 The General Assembly of Rhode Island enacts a law that “prevents all persons keeping house within this Colony from entertaining Indian, Negro or Mulatto slaves or servants.”

1752 In December of that year, Cuffee Cockroach an enslaved African cook of Jaheel Brenton prepared a feast that featured a sea turtle stew for a community gathering held at Fort George, on Goat Island. The “Turtle Frolic” became an annual celebration.

1755 Africans represent approximately 20% of entire Newport population.

1756 Newport Africans begin to assemble each June at corners of Thames and Farewell Streets to elect a “Negro Governor” – a mixture of European and African traditions. This West African tradition is later seen in Boston, Providence, Portsmouth, NH and Connecticut.

1750-1780 Hundreds of Africans in Newport are converted into Christianity as part of the Great Awakening Religious Movement sweeping across American Colonies. Trinity Church, along with First and Second Congregational Churches lead the conversion activities.

1758 Sarah Osborn establishes a school for religious and civic instruction for white and black children under the support of Newport’s Second Congregational Church.

1763 Rev. Marmaduke Brown of Trinity Church opens a school for African children.

1766 A group of free and enslaved Africans take a picnic in Portsmouth led by Caesar Lyndon, personal secretary and clerk for Governor Josiah Lyndon.

1767 Phyllis Wheatley of Boston, America’s earliest African woman poet has her first poem published in the Newport Mercury newspaper in 1767. During the time, Wheatley is close friend of fellow African woman of Newport Obour Tanner.

1768 Signed by “A True Son of Liberty,” an article appears in the Newport Mercury Newspaper under the caption, “If you say you have the right to enslave Negroes, because it is for your interests, why do you dispute the legality of Great Britain enslaving you?”

1772 Mary Brett with support from Trinity Church opens a second school for African children at her High Street (Division Street) home in Newport.

Mintus Northrup is born into slavery in North Kingstown, Rhode Island. He is the father of Solomon Northrup, author of “12 Years A Slave.”

British Customs Schooner, HMS Gaspee is looted and burned off the coast of Warwick. One of the participants is enslaved Aaron Briggs from Prudence Island.

1773 Fortune, listed as an “abandoned Negro,” reportedly set fire to the Long Wharf in Newport causing £80,000 in damage. He is executed for his crime.

1774 Africans John Quamino and Bristol Yamma are sent to study at College of New Jersey (the future Princeton University) to train as Christian Missionaries. These will be the first Africans to attend college in America. The plan is devised by Rev’s Samuel Hopkins and Ezra Stiles of Newport.

1776 American Revolution begins.

Rev. Samuel Hopkins of First Congregational Church in Newport authors “A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of Africans” that he presents to the Continental Congress stating slavery is incongruous to the ideals of American civil and personal liberty.

In a June 6, 1776 letter from John Quamino of Newport to Moses Brown of Providence, Quamino thanking him for emancipating his servants and his “boundless benevolence with regards to the unforfeited rights of the poor and unhappy Africans of this province.”

1778 The 1st Rhode Island Regiment is reformed including 132 enslaved and free African and Indian men. Later to be called the “Black Regiment” they fight with great valor in the Battle of Rhode Island in August, 1778.

1780 A group of free African men meet in the Newport home of Abraham Casey and form the Free African Union Society, the first such society in America.

1781 Rhode Island General Assembly rules in favor of a petition of Quarco Honyman, former slave to the Honyman family that he had served his country during the war and is deemed a free man.

1784 General Assembly of Rhode Island grants the gradual emancipation of slaves. Slaves born before 1784 were to remain slaves for life.

1785 Eleanor Eldridge, a free Mulatto woman was born in Warwick and would go on to become a well-known land and business owner in Providence. In 1838 her memoirs are published describing the life of a free African American woman in Rhode Island.

1786 John Brown of Providence in a November 26, 1786 letter to his brother Moses states, “I lately heard several respectable people say that the merchants of Newport scarcely earned any property in any other trade, that all the estates that had ever been acquired in that town had been got in the trade in slaves from Guinea.”

1787 Anthony Taylor, President of the African Union Society sends letters promoting the return to Africa by free Africans in Newport. In the letter, Taylor describes the situation for Africans in Rhode Island as “strangers and outcasts in a strange land.”

Anthony Taylor and Salmar Nubia of Newport send a letter to Cato Gardner and London Spear of Providence instructing them to urge their fellow African Union Society members to not participate in the African slave trade.

1789 New Goree community is established in Bristol, RI by free Africans. Today the neighborhood is bordered by Wood and Bay View Avenue.

Members of the Free African Benevolent Society in Newport actively develop a plan to return to Africa.

1790 The Providence Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery is incorporated.

1792 African Charity “Duchess” Quamino dies in Newport; recognized as the “Pastry Queen of Rhode Island” and one of the most successful African women entrepreneurs of her time. Her marker is inscribed by Reverend William Ellery Channing.

1793 Sixty-three former members of the Rhode Island 1st (Black) Regiment petition to receive pensions for service during the American Revolution.

1800 Five free Africans own homes on the section of Pope Street in Newport between Spring and Thames streets referred to as “Negro Lane.”

James DeWolf of Bristol is one of the most active slave traders in America during late 18th and early 19th centuries.

1800 -1870 During that era and led by the Hazzard family, 84 “Negro cloth” mills opened in Rhode Island. Rhode Island industrialists bought and processed slave-picked cotton, while southern slaveholders purchased Rhode Island manufactured cloth for themselves and their slaves.

1803 Former enslaved African Nkrumah Mireku becomes the first published African musical composer in America; songs include “Crooked Shanks” and the religious anthem “The Promise.”

1808 In March the Free African Benevolent Society of Newport establishes the first free African school (private) in America on School Street.

1809 The Free African Female Benevolent Society is established in Newport with founding members including Obour Tanner and Sara Lyna.

1812 During the War of 1812, free African Hannibal Collins of Newport along with other African sailors were present at the Battle of Lake Erie under the command of Newport Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry.

1814 The narrative of William J. Brown of Providence is published. Entitled The Life of William J. Brown with Personal Recollection of Incidents in Rhode Island.

1819 African Union Society in Providence evolves into the African Meeting House and later Congdon Street Baptist Church.

1822 Black men are barred from voting in Rhode Island.

1824 The Free African Benevolent Society evolves into the Union Colored Congregational Church located in old Baptist Meeting House on Division Street.

Hardscrabble, a predominately black community in Providence is rocked by a race riot.

1826 On January 4th, led by Nkrumah Mireku (aka Newport Gardner) and Salmar Nubia (aka Jack Mason) a group of Newport Africans set sail for Africa settling in Liberia. The entire party dies of coastal fever within one year.

1830 Pond Street Free Baptist Church organized in Providence, RI

1831 Snow Town, the Providence neighborhood that replaces Hardscrabble, is the scene to a second major race riot.

1838 First public school for black children is established on Meeting Street in Providence.

1839 The Providence Shelter for Colored Children is organized.

1842 At the November session of the General Assembly of Rhode Island meeting at Newport, the Rhode Island Constitution is revised and ratified giving African American men among others the right to vote.

1846 The summer of 1846, African American businessman, George T. Downing opens a restaurant on Bellevue Avenue in Newport to cater to the emerging summer resort market.

1850 African Church located on Wood Street in Bristol, RI. Building also housed a school for Black children.

1856 Thomas Howland becomes first Black elected to public office in Providence as Warden of the Third Ward.

George T. Downing builds the Sea Girt Hotel along a Bellevue Avenue commercial block that would bear his name.

1859 James Howland of Jamestown dies as the last slave in Rhode Island at the age of 100 years.

1860 Isaac Rice homestead in Newport is used as an Underground Railroad stop.

1861 The American Civil War begins.

1863 The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) is organized in Providence, Rhode Island.

Newport and Providence African American leaders begin a movement to fully integrate public schools in Rhode Island.

1865 A group of Newport philanthropists, including George T. Downing underwrite the purchase of land to become Touro Park on Bellevue Avenue.

The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiment is mustered out at Portsmouth Grove.

1866 Dr. Harriet A. Rice was born to George and Lucinda Rice in Newport. She graduated as a top student at Newport’s Rogers High School and in 1882 went on to become the first African American student to graduate from Wellesley College. Soon after she would earn a medical degree at the University of Michigan Medical School. During WWI, she was a physician serving the French Army.

1867 Mary Jackson is born in Providence. She would later work as a statistician at state Labor Department and during WWI, was appointed as a Special Worker for Colored Girls on the YWCA War Work Council.

George T. Downing successfully leads the integration of public schools in Rhode Island.

1869 Rev. Mahlon Van Horne assumes the pastorate of Union Colored Congregational Church on Division Street in Newport.

1870 The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified prohibiting the restriction of voting rights “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

1871 Painter Edward Bannister and his wife Christiana settle in Providence. He is part of founders of Providence Art Club and RISD.

1872 Rev. Van Horne becomes the first African American member of the Newport School Board.

1875 In July 1875 the Congdon Street Baptist Church building is completed in Providence.

St John’s Episcopal Church in Newport is founded at the Point Neighborhood home of African American Peter Quire.

1882 The Daisy Tonsorial Parlor is established at 148 Bellevue Avenue by African American business and civic leader, Fredrick E. Williams.

1883 On October 15th, the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional and declared that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids states, but not citizens, from discriminating.

1885 Rev. Van Horne of Newport becomes the first African American member of the General Assembly of Rhode Island.

1885-90 George T. Downing is member of the committee responsible for the Bellevue Avenue extension to Bailey’s Beach in Newport.

1887 Dr. Harriet A. Rice of Newport becomes the first African American to graduate Wellesley College. Soon after, she earned a medical degree at the University of Michigan.

1888 Sisseretta Jones of Providence becomes an international singing star.

1890 Rhode Island enacts a law that establishes the “Home For Aged Colored Women.” Christina Bannister is the leader of the effort and later the home would bear her name as Bannister House in Providence.

1891 The first Black owned and operated newspaper in New England, Torchlight, is established by John Minkins in Providence.

1892 Over 160 documented African American lynching’s in America; the highest annual total in history.

1893 The Breakers Mansion, Newport’s grandest summer cottage is built by Cornelius Vanderbilt II. The Newport Gilded Age has arrived.

J T Allen and his brother David arrive in Newport and soon established the Hygeia Spa at Easton’s Beach and dining facility in the Perry Mansion on Touro Street.

1894 Dr. Marcus Wheatland becomes the first known African-American physician to live and practice in Rhode Island. Dr. Wheatland was nationally recognized as an early radiology specialist.

John Hope graduates from Brown University and later becomes President of Morehouse College.

1896 United States Supreme Court issues Plessy v. Ferguson ruling decided that “separate but equal” facilities satisfy Fourteenth Amendment guarantees, thus giving legal sanction to Jim Crow segregation laws.

President William McKinley appoints Rev. Van Horne of Newport to become U.S. Consul to St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies, serving through the Spanish American War.

1897 Newport born Dr. M. Alonzo Van Horne graduates from Howard Medical School and becomes the first African American dentist in Newport practicing at 47 John Street and later at 22 Broadway.

1898 During the Spanish America War sixteen regiments of black volunteers nationally are recruited and four see combat.

1899 Members of the (African American) Women’s League Newport gather led by Mary Dickerson who owns a dress shop on Bellevue Avenue.

For more information, go to the 1696 Heritage website: https://bit.ly/3h3RjAy

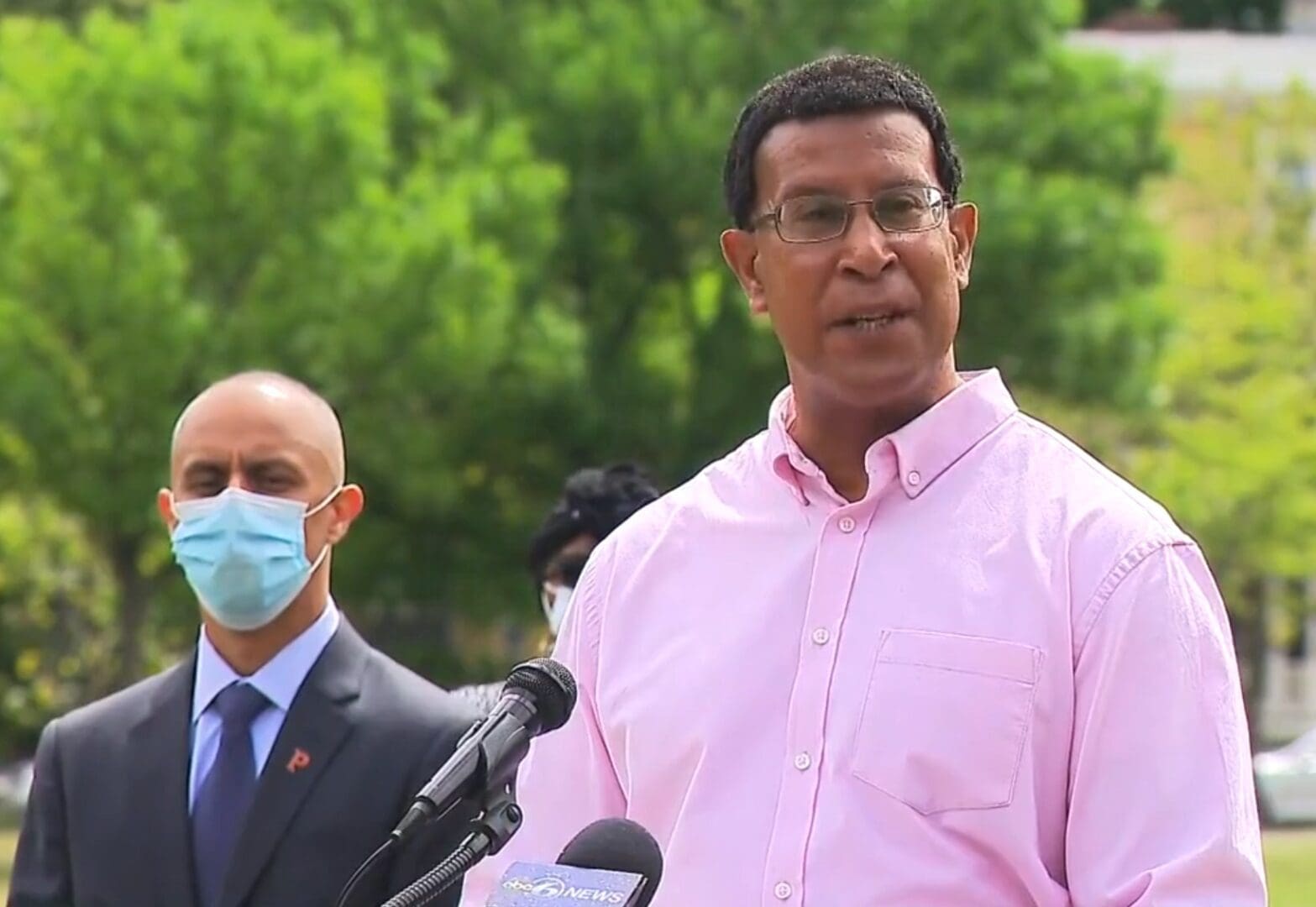

Photo, top: Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza & Keith Stokes, 1696 Heritage