Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 19.06.25 (Military Funerals, Job Fair, Benefits, Events) – John A. Cianci June 19, 2025

- East Providence First in U.S. to Equip All Firefighters with PFAS-free Gear June 19, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Saffron Bouillabaisse with Tarhana Lobster Jus June 19, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 19, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

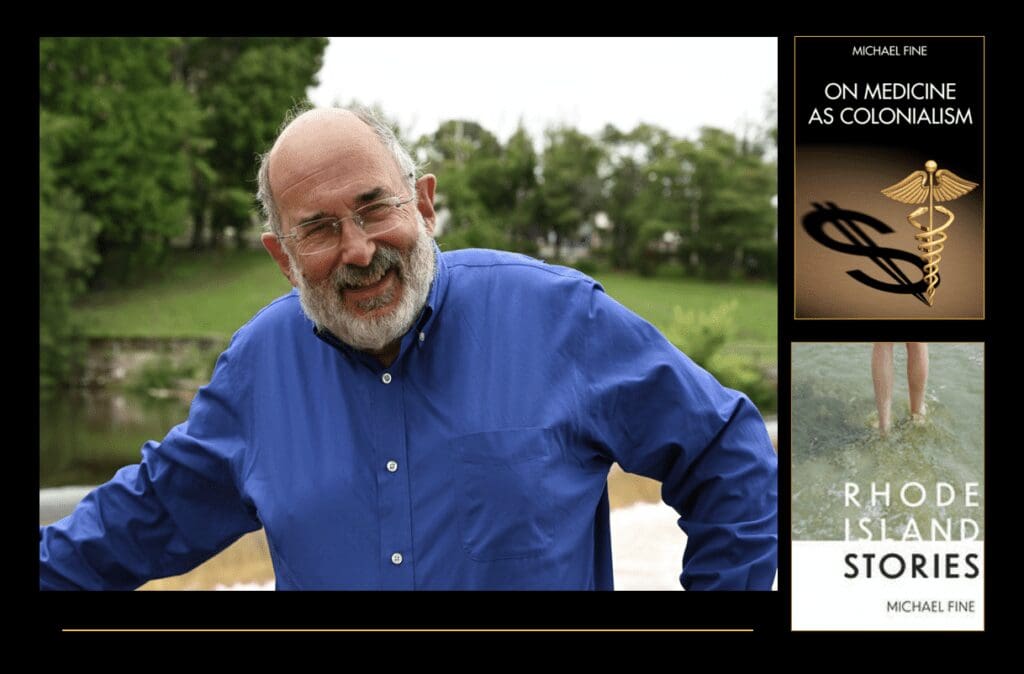

Now Is the Cool of the Day – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

“He wants a situation-ship not a marriage,” Dvorah said.

“And there’s no such thing as global warming, right? Or climate change. Or whatever,” Althea said. “Is there someone else again?”

“I don’t think so,” Dvorah said. “At least not at the moment.”

“Someone in your life?” Althea said.

“Unfortunately, no,” Dvorah said.

_

It was midday in the summer and hot, despite the breeze. They were sitting outside at a café overlooking the ocean under a red umbrella with the name of a beer emblazoned across it. The umbrella snapped and flapped in the wind. Sailboats glided across the water in the channel of ocean near them, their white sails billowing, filled with the good stiff wind. The sky was blue. A bright blue, with only patchy white clouds. People on yellow and red jet skis skidded across the water, leaving a semicircular plume of water behind them. Two or three parasailers floated in the breeze off the coast, not close enough to see clearly but close enough to be seen after all, to provide color and movement in the sky. There was a strong surf. The waves rose and crashed hard onto the beach, a resounding but distant rhythm, a powerful backdrop. A propeller plane towing a banner flew low in the sky just offshore, following the beach which was covered with beachgoers and beach umbrellas and small beach tents. The drone of that plane was an insistent hum, noticeable but somehow not disturbing, a kind of mantra or chant that was almost calming, given all the motion and activity surrounding them.

A truck rumbled by out on the street and a motorcycle or two screeched up the same street. Seagulls drifted above them, cawing as they rode the thermals and sea breezes.

“Couldn’t that be good for you? A situation-ship? Kind of empowering.” Althea said.

“Yes and no,” Dvorah said.

“What’s driving this, then?” Althea said.

“I don’t know. We’re stale, that’s true. But we’ve been stale for years. No more of the lovey-dovey stuff, not for a long time. No excitement when he comes into the room. It’s a chore to travel together. Even to spend time together. But it’s been that way forever, ever since the kids left,” Dvorah said.

“Sounds deadly,” Althea said.

“Not deadly. That’s not really the word. Disappointing, maybe,” Dvorah said.

“But you are both used to it and have made your peace with it. Allowed distractions to happen, “Althea said.

“Allowed distractions to happen,” Dvorah said, and looked out on the bay and little port, at the sailboats and the parasails and jet skis, at the way the sunlight was reflected and refracted by the water-trails from the jet skis, little rainbows that came and went, a spray of jewels over the water that disappeared as soon as it became visible.

“So is this a post-midlife crisis? He could buy himself a Porsche,” Althea said.

“I don’t know,” Dvorah said. “Men get lost in themselves. Cosmic soul sickness. A kind of spiritual dislocation. Where their souls go looking for what’s missing, for their cosmic lost object, something that was never there and never will be.”

“Ted? Looking for a cosmic lost object? I don’t think so,” Althea said. “He might go looking for a lost golf ball. Or for a quickie in the bushes with someone in a low-cut dress who’s had three martinis at a garden party, after the sun has set. I don’t think there’s more there than that. But perhaps I am missing something.”

“Perhaps. Perhaps not,” Dvorah said, and she looked out at the sea again.

“I see this as an opportunity,” Althea said. “Your moment to shine. Your moment to live as you want to live. To define yourself. To live your life fully, if you know what I mean. Satisfaction is something every woman deserves.”

“But there is something to marriage, don’t you think?” Dvorah said. “Companionship. Trust. Stewardship. Stability. Having a family together. Putting other people before yourself. Building and maintaining the community. Values. A star to steer the ship by. That sort of thing.”

“Old hat. Passe. You’re living in another century,” Althea said.

“You think? People have been getting married for hundreds of years,” Dvorah said. “I don’t think we should toss away three million years of human cultural development like it was just kitty litter.”

“Now that’s fake news if ever I heard it,” Althea said. “Marriage was always just transactional, a business arrangement, to bring the resources of two families together, the sum of the parts being greater than the whole. Or so the story went. And human beings have always played around anyway. We’re like monkeys. Baboons. Chimpanzees. Bonobos. Rabbits. It’s in the blood. We breed with many males so no one knows who the father is, so all males think all babies might be theirs and protect them. We have constant arousal; we don’t just go into heat once a year with the seasons. And so forth.”

“And no one ever really lived like this.” Althea continued. “Paired off just two together, two people against the world. When we lived in little huts, anything and everything went on in the woods and in the haystacks. The Victorians invented prudery so that working people would work in their factories, slaves would work in their fields and not get too distracted by each other, so they’d keep working, keep producing. Or not. So they wouldn’t put down their machines and their hoes to get jiggly. Husbands lived with their wives, maybe. But they spent their time in the factories and the fields, men hanging out with men, women hanging out with women, but whenever and wherever men and women got together, sparks would fly. So to speak. Delightful sparks.” Althea said and batted her eyes as she smiled sweetly. It was a fake, knowing smile.

“I suppose you’re right,” Dvorah said. “I just always wanted to think that there is more to us than that.”

“That’s all there is, I’m afraid, “Althea said.” So make the best of it, sweetheart. Lemons into lemonade. Make hay while the sun shines. Eat dessert first. Life is uncertain.”

Just then there was a commotion on the beach. Voices calling out. A knot of people, a little crowd, gathering where the waves were breaking.

“Never a dull moment,” Dvorah said as she stood up suddenly. “Sorry. Duty calls.” She ran off, tossing her white cloth napkin onto the table as she went.

Althea shook her head. Some people never learn. Can never let well enough alone.

The man was still in the water when Dvorah got there. Dvorah was still holding the beautiful red soled shoes she’d kicked off as soon as she got to the beach.

Two people, one on each side of the man in the water, had their hands under his armpits and were holding his head and thorax out of the water.

“Is he breathing?” Dvorah said, in her mom voice, her outside voice. She dropped her shoes on the beach and plunged into the water. She knelt next to the man the two people were holding up.

“Yeah,” one of the men said. “But not moving.”

“Call 911,” Dvorah said. “Can you speak?” she said to the man in the water. “Don’t move him,” she said to the people holding him up. Waves washed over them and pushed them toward the beach. Then the undertow tugged everyone in the water toward the sea.

“Don’t move him,” Dvorah said again.

“We can’t stay here forever,” one of the people holding the man in the water said, a man in his forties with wet slicked-back dirty blond hair. “Tide’s coming in.”

“Can you speak?” Dvorah said.

“I. Can,” the man in the water said. “Just. Short. Sentences.”

“Can you move your arms and legs?” Dvorah said.

“Do. You. Think. I’d be. Lying here. Like this. If. I. Could move?” the man lying in the water said. He was a trim fellow in his sixties, old but in good shape, with the big shoulders of a swimmer. His hair was thin and his skin both tanned and sallow.

There were sirens and flashing lights, first on the hill above the beach, and then in the parking lot next to the beach.

“It won’t be long now,”: Dvorah said. “How did you get hurt?”

“Body. Surfing,” the man said.

“Did you hit your head?” Dvorah said.

“No. I. Stubbed. My toe,” the man in the water said. “Yes. I hit. My. Head. Wave. Picked. Me. Up. Threw me. Into the sand. Headfirst.”

“Don’t move him,” Dvorah said a third time. “Mechanism of injury. He could have a neck, er, injury.”

The crowd parted. Two EMTs carrying red jump boxes and a policeman came to the waterside.

“Wait,” the man in the water said. “I’m getting the feeling back. In my feet.” He moved his legs a little in the water, flexing his knees.

“Let’s get you up, brother,” the man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair said, and he started to lift the injured man out of the water.

“Don’t. Don’t move him,” Dvorah said. The man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair paused and eyed Dvorah suspiciously. “Get a back board and a cervical collar,” Dvorah said to the EMTs and the policeman on the shore. “Now.”

“We don’t got a backboard with us,” one of the EMTs said. “We’re in the jump vehicle. The backboard is in Rescue One and that’s on a hospital run.”

“See?” The man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair said.

“Feeling’s coming back in arms,” the man in the water said.

“Don’t move. Don’t move anything. I don’t care who tells you you can move,” Dvorah said.

“Bring him into shore,” one of the EMTs said. “We’ll stabilize him on shore.”

“No!” Dvorah said.

But it was too late. The two people holding the man started to tow him toward shore. The water held his body up. The second person, a portly woman with long black hair, a number of silver earrings, and a nose clip shrugged and followed the lead of the man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair.

“I’ll see if I can get mutual aid from Middletown, Portsmouth or Jamestown,” one of the EMT’s said, and he started speaking into his radio.

But the man in the water was moving his arms and legs now. The two people holding him brought him to shore, where he lay for a moment. Then he pushed himself up with his arms, as if he was doing a pushup, and then the man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair helped him to stand. Someone brought over a beach chair and he sat in it.

“They got the Gator coming,” one of the EMTS said.

“I can’t believe what you just did,” Dvorah said. “Don’t you understand mechanism of injury?”

“Who the hell are you?” the man with the slicked-back dirty blond hair said.

“He needs to be on a backboard and immobilized in a cervical collar before anyone moves him again. Like now.” Dvorah said. She knelt next to the man who had been injured and who was sitting in a beach chair.

“Please don’t move.” Dvorah said. “Please wait until they bring all their equipment onto the beach.”

“I’m okay,” the man said. “The feeling is back. I think I can walk now.”

“Please just sit still,” Dvorah said.

The man sat still, thank God. The crowd dissipated. Another prop plane towing another advertising banner flew over, the drone of the plane audible when the waves receded but disappearing whenever a wave hit the breakers. A squat green vehicle with a flashing overhead light came onto the beach and parked a few feet from the man in the beach chair. Two new EMTS came over and helped the injured man to his feet.

“Won’t you please please put him on a back board?” Dvorah said. “And in a cervical collar?”

“Good idea,” one of the EMTs said. They stopped what they were doing. Another EMT rummaged through a box on the back of the squat green vehicle, brought over a cervical collar and wrapped it around the man’s neck and then secured it with Velcro straps while the injured man was standing on the beach. Then they walked him to the squat green vehicle, had him lay down on a varnished wooden board on the bed of the vehicle, and then secured him to the board with more Velcro.

“Please take him to Rhode Island Hospital,” Dvorah said. “Do not pass Go. Do not collect two hundred dollars. Just go. And keep his spine immobilized until you get there.”

“Who the hell are you?” one of the EMTS said.

“I’m one of the trauma surgeons at the hospital,” Dvorah said.

“Oh,” the EMT said. “Got it.”

Dvorah looked around.

“Damn. Damn damn damn damn,” she said.

Her red-soled shoes laying in a puddle of water a few feet away. The incoming tide had washed over them and moved them from where she had left them but hadn’t carried them out to sea. At least one of the spectators hadn’t walked off with them. She picked them up and tried to dust the sand off them, and then walked back toward the restaurant.

“Well, aren’t you a sight,” Althea said, when Dvorah came back to their table, walking gingerly in bare feet.

“Children and fools,” Devorah said. “I can’t believe that guy didn’t get pithed. Didn’t get his spinal cord transected and didn’t end up a quadriplegic, completely paralyzed and on a ventilator. At least not yet. They have no idea what they’re dealing with.”

“Sounds messy,” Althea said. Her phone rang. She looked at it and then silenced the ringer.

“We lucked out.” Dvorah said. “So far. But he’s not out of the woods yet.” She stood and brushed herself off.

“What a fucking mess,” she said as she marched herself off to the ladies’ room.

Althea’s phone rang again. She looked over her glasses, around the room. The she clicked to answer and put the phone to her ear,

“Ted,” she purred. “I thought you’d never call back.”

_

Many thanks to Catherine Procaccini for proofreading and to Brianna Benjamin for all around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short story and his new health care series What’s Crazy in Healthcare.

Please invite others to join by sending them the link here. Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.