Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

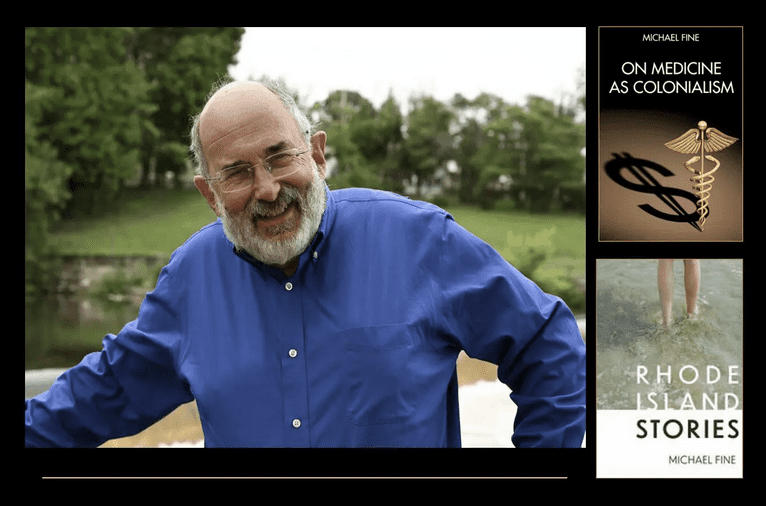

Mourning Sinwar – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

© 2025 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Asaf was thinking about the endless antilogic of revenge and retribution, of them attacking us to show they can, and us hitting them back with overwhelming force, showing strength to deter attacks.

We hit them because they hit us. They hit us because we hit them. These blood feuds only mushroom, as any response provokes a worse reply, as if anything either side does can heal the underlying lesion, the wound of history, the genetic trauma, our and their fear, our and their anger and arrogance, all original sins. We of all people understand exile and the yearning for a place and a homeland it creates. Hope gnaws at us, as if finding this lost object is all it will take to complete us as human beings, as if making that homeland safe and secure would make us become whole. But the lost object isn’t a homeland. The missing piece is who we are, inside us.

Life can never be safe or secure because it always ends. Love is not perfect because what we love is the other, who will die, betray or disappoint us. Time creates loss and death is certain. Our yearning is the yearning for life everlasting, not a place, and for unconditional love that we can give and receive without limit, neither of which exists.

The warrior’s creed — kill or be killed — is not compatible with a society of doing unto others as you would have them do unto to you, where no one can or should ever profit from another’s misfortune. When we try to live humbly, they come for us and kill us anyway, making us the same as everyone else, despite our hope and struggle to be better than others, and to be better than ourselves.

We fight fiercely for our freedom, but we cannot govern ourselves.

What we learned in exile and then forgot is that human life is holy, that there are only brief moments of peace and only in small communities who suppress their lusts by constantly reminding themselves of their insignificance, compared to God. In exile we learned that self-discipline and self-restraint are the only pathways to making the wheatfields productive, the grapevines yield, and the sheep and cattle fatten and multiply. Follow ten simple rules and you will become as numerous as the stars. Until you’re not.

In exile we learned that government is toxic to our souls, that stepping back from the material world of profit and control lets us experience the beauty of the earth and life itself — all lessons that we lose sight of when the vortex of attack and reprisal takes hold. We also learned that we must always be ready to defend ourselves and always be ready to cut and run. Because when man plans, God laughs.

So I mourn Sinwar despite myself, thought Asaf. I’m glad the leader of Hamas is dead. But Sinwar himself was still a man, with just one life, and his death also saddens me even though his elimination, if that is what we must call it, felt just and right. We lose something with each death, and something extra with each violent death. We lose a soul, which can always turn back to God, but only if the body lives. And we lose an overriding commitment to the value of human life, as a shared value that we need to hold in our collective soul if we are to make a world at peace, a world of love, our land a land of milk and honey, and we lose the very world we crave, which we must now and always mourn the loss of, and still seems completely out of reach.

I and we know better than anyone that when one man falls, another rises to take his place.

There was that video. A man sitting in a chair in a bombed-out building, injured and alone, who throws a stick at a drone that is taking pictures of him, a last act of defiance, of resistance. Good riddance to bad rubbish, Asaf thought. It isn’t my fight anyway. They are crazy, all those people, every single one of them, on both sides. The Palestinians, who don’t seem to be able to quit the suicide bombs, the rockets and a thousand other random acts of violence, after which their own people die in big numbers and nothing changes; and the Israelis, who keep killing more people, more women and children every time they get the excuse to do so.

We’ve become one sad people, united only by death, destruction, anger and fear.

There don’t seem to be any reasonable options for the Palestinians now, Asaf thought, which puts the world between a rock and a hard place – intervene, though it isn’t clear what that intervention should look like – and pull the warring parties apart, putting everyone who tries to intervene at great risk themselves. Or sit back and watch a whole people and all their homes, schools, and hospitals bombed into oblivion. Not my fight, Asaf thought again. But such sadness!

Asaf was a doctor’s son from Raleigh, North Carolina who worked in tech and drew when he was bored. He’d sit in meetings and draw pictures of the people across the table to illustrate his meeting notes. He had a wife who came from Asheville.,Ashleigh, a willowy strawberry blond, a tattooed middle-school teacher, and a seven-year-old son named Will who was in second grade and liked The Boxcar Children, was seriously into Legos ,and liked to play outside with three friends in their neighborhood. Their neighborhood was a little planned community around a small lake, a development of low-rise condos, built in entryways of four condos with a single entrance, with asphalt foot paths that connected the houses. There was a central playground and a pool in the community house.

Asaf, Ashleigh and Will lived in a first-floor condo, so they had a yard and a walk-out garden. Asaf had spent one weekend assembling and erecting a very nice swing set, which had a platform with a tent on top and a little green slide that had ripples in it. Will would often go out to play in the afternoons after school while Asaf worked from home at his computer, and more often than not Will played in their yard by himself. After a few minutes of swinging and climbing, he’d just sit on one of the swings, looking out at the lake, and sway back and forth without swinging, as if he was dreaming or imagining a different world. There was a fence at the back of their property, and Will was old enough to climb over it if he chose to, but Will was a good kid, a quiet, respectful and loving kid, who never thought to do that. He wasn’t a kid who acted out or broke rules. He was a kid who listened, learned, and dreamed.

It was late October. The leaves had turned red, orange, and now yellow. Many leaves had already come off the trees and lay yellow, brown, and red on the asphalt path, rustling in the slightest breeze. The woods across the lake were yellow and the brush around the asphalt paths was yellow and red as well, as if the world was waiting with bated breath for the next step, for the disappearance of those leaves, and for winter, which loomed but hadn’t yet come. The air was pungent with maple and pine.

Then the sky flamed orange and red, and the angled pale sunlight glinted into your eyes every time you faced southwest. The air was warm, for that time of year –- still too warm for sweaters and jackets, but cool enough so that the temperature dropped when the sun went down because the clear air no longer held the sun’s warmth. People hurried inside when the sun dropped lower in the sky, even while the air was still warm. There was a hint of smoke from fires that started in the fireplaces in anticipation of cool and even cold nights, but there had been no frost yet. The cold nights had not yet come. The first frost was long overdue.

It was hard to characterize the man wearing a blue peacoat, which was heavier than the warm air called for. He was tall and brown-skinned, like Asaf himself. He was balding, and the sun reflected off the shiny parts of his bald head. He was a little hunched over, and if he had been closer, Asaf might have seen that his eyes were moist and his nose was running, as if he had a cold. But Asaf didn’t think anything of it when he looked up and saw a man walking on the asphalt path between the back of their little lot and the lake. People walk there. They walk around the lake. There was a gatehouse that stops cars and asks for identification as you come into the development, though the gatehouse was occasionally unattended. There is only one road into the development. You wouldn’t know the development even existed if you drove or even walked by on the main road. There was a driveway, like any other driveway, and a small sign with the street address. Quiet. Understated. Asaf and Ashleigh liked it that way.

Asaf looked away. He went back to his work.

The man didn’t say anything when he approached the fence. Will sat on his swing and drifted back and forth, his feet on the ground, moving enough to feel like he was unrestrained, but not swinging, the tiny movement reflecting the patterns of his imagination, which was more like dreaming than thinking. He was looking at the orange and red of the western sky over the lake, and how that light caught in streams of clouds, the light poking in and out of those clouds and streaming through them in places, like water streaming over a waterfall, or a warm wind streaming into a cold room, the streaming of warmth, light, and abundance. Will noticed the man putting his hands on the fence, but it was notice, not looking at, a child noticing an adult, with the expectation that the adult is knowing and in control and the child is there to notice, watch, listen and learn.

Curious, Asaf thought, the next time he looked up. I wonder where Will is? He must have come into the house and I didn’t hear him. Or maybe he’s sitting at the table near the house, where I can’t see him. He’s been told not to sit there, where I can’t see him. What’s up with that?

Asaf went back to his work.

A few minutes passed. Asaf raised his head again, to listen. It was getting dark. And colder. The orange in the sky had faded to a faint dirty yellow and wasn’t intense enough to throw off any light. There was a blueness and a greyness under the trees and over the lake, so what had been rich with detail a few minutes ago, with trees and houses, docks and boats, was now just broad bands of gray, brown and black — the land one tint, the water a different tint, the land beyond the water a different tint yet — and the sky was just a touch lighter, and rapidly fading to dark blue and black.

No TV on. Maybe Will is on his iPad.

Asaf stood and went to find Will. Just double-checking.

They sat separately at the trial. They were living apart now, Asaf and Ashleigh. Ashleigh had, with lots of therapy, started to entertain thoughts of forgiving Asaf, at least intellectually, but she still felt revulsion, and distance, between them, and wasn’t sure she could ever let her guard down around Asaf or ever trust him again. But Asaf was completely unable to forgive himself, and had shut down, like a house with a big forked main electrical switch that someone had pulled. He was not present, even to himself.

It wasn’t clear to Asaf why there had to be a trial. They found the man still standing in the lake, Will’s beautiful body still in that man’s thin, hateful, disgusting hands, those hands wrapped around Will’s throat, holding the body of their beautiful and amazing child under the water, Will’s face blue and white and his limbs already cold, that man who destroyed in those few moments everything that was good and true in the world, and with that destruction any reason that any person on earth should want to continue to live here.

He was pleading not guilty by reason of insanity, that man. But the whole thing was insane. The whole world was insane. It had once been a good world. But now it was nothing, and Asaf despised living.

Asaf could not look at the man and was grateful they sat him behind the state’s attorney, with a row of lawyers between them, so if he looked over to the other side of the room by mistake, he did not see the man’s face or even his head, because other people blocked that view. The back of that man’s head, from time to time. But nothing more, and never his face.

Ashleigh came the first day and sat in the same row as Asaf, her parents and sisters between them, but she did not stay. Her parents and sisters did not look at Asaf. They had tried and convicted him in their own minds, as he had tried and convicted himself. He did not look up.

It was a quick trial. The arresting officer. The witness, out walking her dog, who saw a man standing in the water in late October, who called the police. None of the facts of the case and no evidence was in question. Somehow, mercifully, they did not call Asaf and somehow, miraculously, they did not call Ashleigh. They did not call the man himself to testify in his defense either, because there was no denying what he had done. They might call him later though. For the sentencing phase. So the judge could rule on the insanity defense.

Then, in the penalty phase, they called the forensic psychiatrist.

It was torture to listen. Asaf didn’t care. He didn’t want to hear. It didn’t matter. There was nothing anyone could say that would change this truth. His beautiful son was gone. His marriage was gone. His own life was over.

But he made himself sit there and listen anyway. He was accusing and convicting himself. A way to punish himself. Each word a lash. Each moment a moment on the rack. Each fact a burning coal or a lit cigarette to burn every part of his body. He had to sit there and remember. He did this by looking away, by inattention. The man in the dock was the instrument. But Asaf himself was Will’s destroyer.

The psychiatrist was a thin tall man who spoke in a flat voice. It was all lies, all distortions, all manipulation, every word of that man’s testimony. A diagnosis, self-treated by drugs of abuse. Voices. No ego function at all. The fractured childhood, the violence, the history of repeated, violent sexual abuse by multiple people, The absence of any meaningful parental figure. Likely identification with any child as a wish object, as the representation of the life he didn’t have and then the rage about what he didn’t have, all of that likely unconscious, and transmuted in the imagination into those voices and that religious iconography, the need to baptize, which was the need to clean the self of what could never be cleaned, all meaningless details. They didn’t care about Will. They didn’t know Will. And they could never bring him back.

And then they put the man himself on the stand. You might want to leave the room, the assistant DA had told him, when they prepped him. We are really sorry for this. So sorry. But it is part of every trial in which the defendant has been judged competent to stand trial but is using an insanity defense.

He looked at the man for the first time.

Asaf remembered the man’s partially balding head and his skin, which was the same color as Asaf’s skin. The rest of him was completely different, of course. They had put a suit and tie on the man. Who looked straight ahead, not in the direction of all the voices he had been hearing that day, which had him looking from place to place as he walked on the black paved path. There was no lake sunlight reflected off the lake. There was only the too-white fluorescent light, and the honey-colored oak of the judge’s podium and the witness stand. No pinging or beeping of a computer or a cellphone. Only the sound of chairs as they scraped against the marble floor of the courthouse.

Asaf gripped himself. I want to kill him, he thought. I want to get away, he thought again. I want my son back, my beautiful perfect sweet son, he thought, and my life and self back. All those thoughts happened at once, ripping him apart while he sat still in the hard wooden chair, alone in the courtroom filled with people.

A series of questions. Yes he was taking his medicine. The day, the date, and the year. The president. He understood he was on trial for the capital murder of an eight-year-old child. He didn’t remember that day. But he was sorry and would never have done such a thing if he was in his right mind.

In his right mind? Is there such a thing in this universe, Asaf screamed inside his head. Where we have suicide bombers? People who bomb cities and villages in distant places, reducing everything to rubble, burying hundreds while we stand and watch. Who rape and murder. Who steal and lie. Who design weapons of mass destruction. Who want to expel, to blame, to castigate, to slander. Who make checkpoints with machine guns and shoot rockets at one another. Who profit as they poison the air and the water. And who posture, always distorting the truth. All of them, on both sides crazy, each in their own way. None of us are in our right minds. Not now. Not ever.

He is taking his medicine now, Asaf said to himself. Why wasn’t he taking his medicine that day. What good will it do now if he always takes his medicine? What difference will it make if he never takes his medicine again? Why am I so alone?

An eye for an eye! His soul cried out. A life for a life!

And then the man in the dock looked around the room, searching for something, as if there was nothing inside to tell him where he was or what was what, as he looked for someone or something he recognized, some safe harbor, some anchor. As if he himself was frightened and alone.

As he searched the room for some familiar face, something he could recognize and hold onto, his gaze found Asaf, who was looking at him in much the same way.

He’s alive, Asaf found himself saying to himself, as much as I hate him. A human being, despite everything. In spite of what I want to think. One I hate with all my soul.

Their eyes locked. There was a human being in there, despite everything Asaf felt and wanted to believe.

Suddenly Asaf felt his hips and back spasm. He felt his chest cave in. He felt his shoulders collapse.

The light became bright and suddenly Asaf was standing, his hands near his head but spread apart, fingers outstretched.

Then Asaf spun around. He closed his eyes. He tore his shirt open, rending the fabric. He put his thumbs over his ears and his hands over his eyes. Then he knelt down and pulled himself into a ball, burying his head in his lap.

Life is precious, he thought. Despite its endless pain.

He stayed on his knees in a ball, unable to move or think, until the marshals came and carried him away.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.

I just read Dr. Fine’s short story. It’s philosophical, chilling, … and beautifully written.