Search Posts

Recent Posts

- It is what it is: 1-22-25 – Jen Brien January 22, 2025

- It’s Sour Grapes time! – Tim Jones January 22, 2025

- Johnson & Wales University celebrates their first 16-month nursing program graduates January 22, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for January 22, 2024 – Jack Donnelly January 22, 2025

- Dr. Patrick T. Conley, Rhode Island’s first Historian Laureate, retires January 22, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

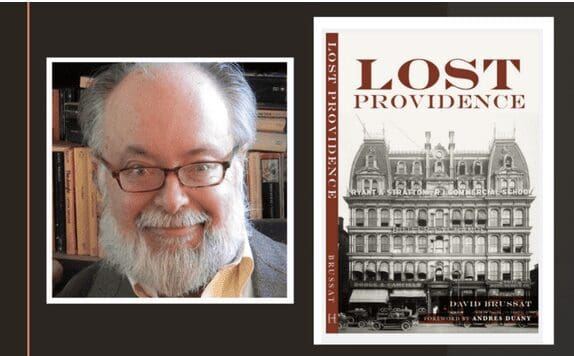

LOST Providence, The Downcity Plan, II – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Editor’s note: This is the bottom half of the 22nd and final chapter, “The Downcity Plan,” from Lost Providence. Chapter 22 concludes Part II of the book, whose final two chapters record the two major projects that sparked the Providence renaissance, which followed a series of major hiccups in the city’s development, which have been described in the other chapters of Part II, reprinted here over the past several months. The epilogue, which I’ve not yet decided to reprint, sums up the lessons Providence and other cities should learn from our city’s recent decades of history.

***

Months prior to my interlude at the window of the Turk’s Head Club with Journal publisher Metcalf [see Chapter 19, “We Hate That”], while in town for my first interview with the paper, I went to fetch a shirt at a laundry in the Arcade near my hotel, the Biltmore. I entered from Westminster Street. Afterward, I exited the Arcade at the other end, onto Weybosset Street, and happened to turn my head left. I saw the curved row of old commercial buildings bending toward Weybosset’s meeting with Westminster at the Providence River. I was struck by its beauty. I said to myself, “I have got to live in Providence.” This was half a decade before I began to conceive of myself as an architecture critic.

[Less than five years later, after I became that critic, I began to write about downtown’s renaissance, including the Downcity Plan.]

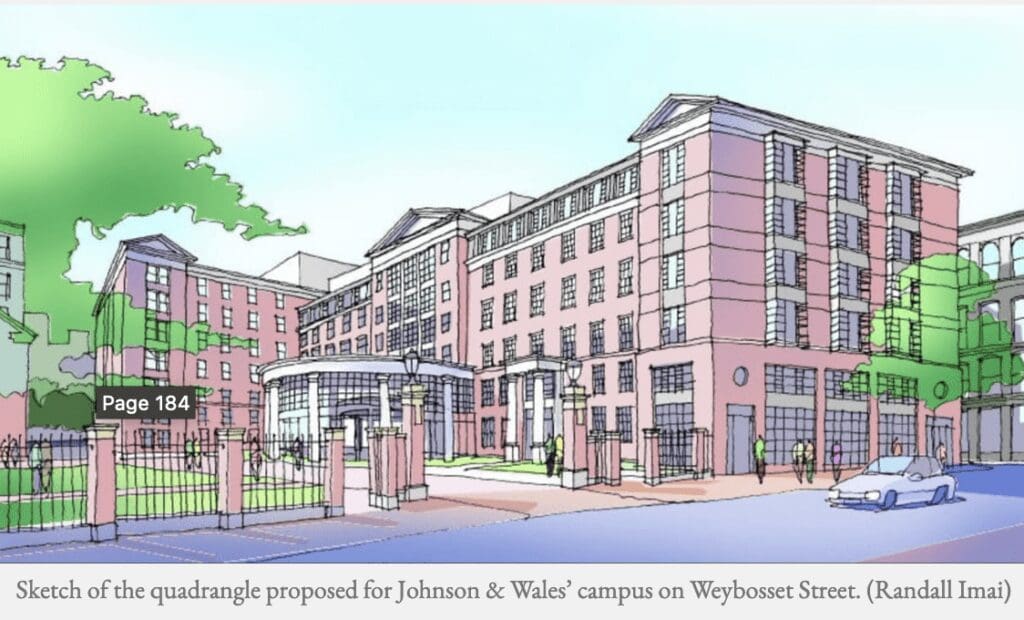

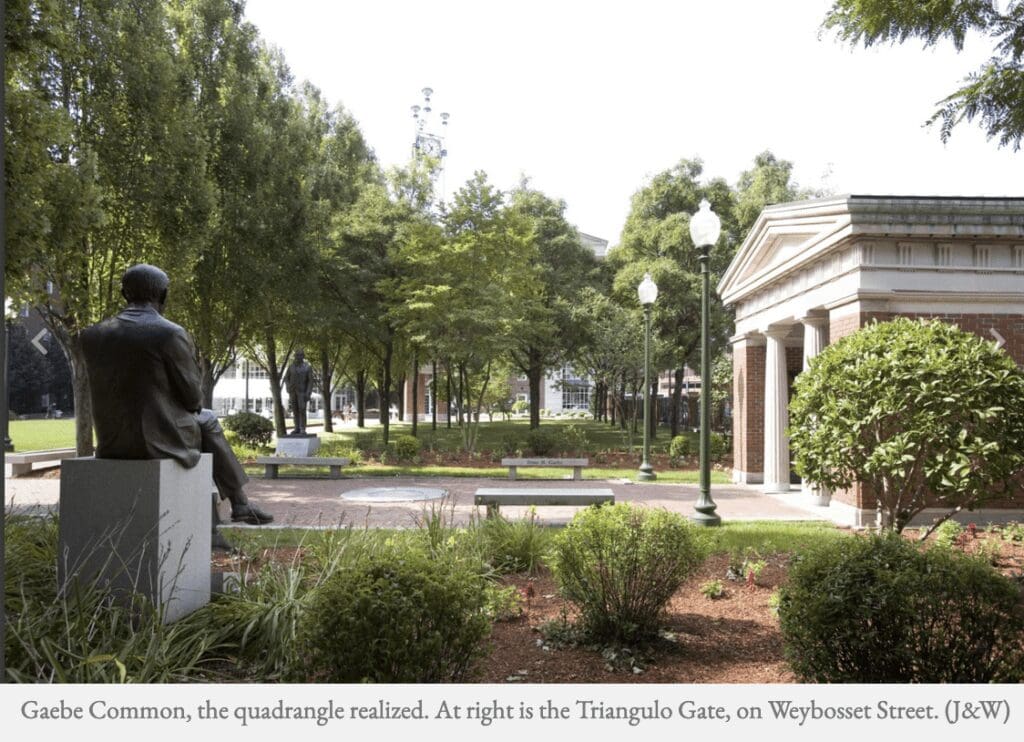

Later wrinkles in the Downcity Plan included a historic district overlay for the downtown master plan, then the plan for a downtown academic quadrangle for Johnson & Wales University and finally an even more ambitious downtown plan in 2004, an effort to connect the city center to neighborhoods beyond Route 95.

–

The first residential rehabilitation, the Smith Building (1912), was completed in 1999, the same year Providence Place mall opened. Before the next decade was out, five other downtown building rehabs housed two hundred new units and shops on the ground floors. Other building owners followed suit. Eventually, although little of the more ambitious 2004 plan has been accomplished, many earlier proposals have been, and they bore considerable fruit. Downtown’s popularity had become the economic basis for several proposals to build new residential towers in Capital Center, two of which were built, including the Westin addition, with hotel rooms and condominiums, and the Waterplace Luxury Condo twins. A proposal in late 2016 to build three residential towers of thirty-four, forty-four and fifty-five floors on the vacant Route 195 land raised hopes that there might indeed be a big market for living in or near downtown – predictably, however, they were way out of scale, way out of place and way out of character for Providence. [In 2023, just a few weeks ago, its developer, Jason Fane, who had ridiculed the historical character of Providence, pulled the plug on his ridiculous project, which by then had shrunk to one building.]

Buff Chace has continued rehabbing buildings, mainly for lofts, and recently proposed yet another set of downtown rehabs on Clemence street, an alley running from Westminster to Weybosset. This project includes the construction of a new residential building. [In 2022, he completed a lovely addition to his row of buildings along Westminster, and the Nightingale Building on the Journal parking lot between Fountain and Washington streets, with 143 apartments above a grocery store.] The number of shops, restaurants and arts venues has continued to grow. Schools keep moving facilities into downtown, stuffing Joe Paolino’s “jelly doughnut” to the max [That what he called his theory that downtown would attract adjunct university facilities in abundance, as described to me as early as 1992.] To compare today’s downtown with that of 1984, when I arrived, is to define success in the art and science of urban revitalization.

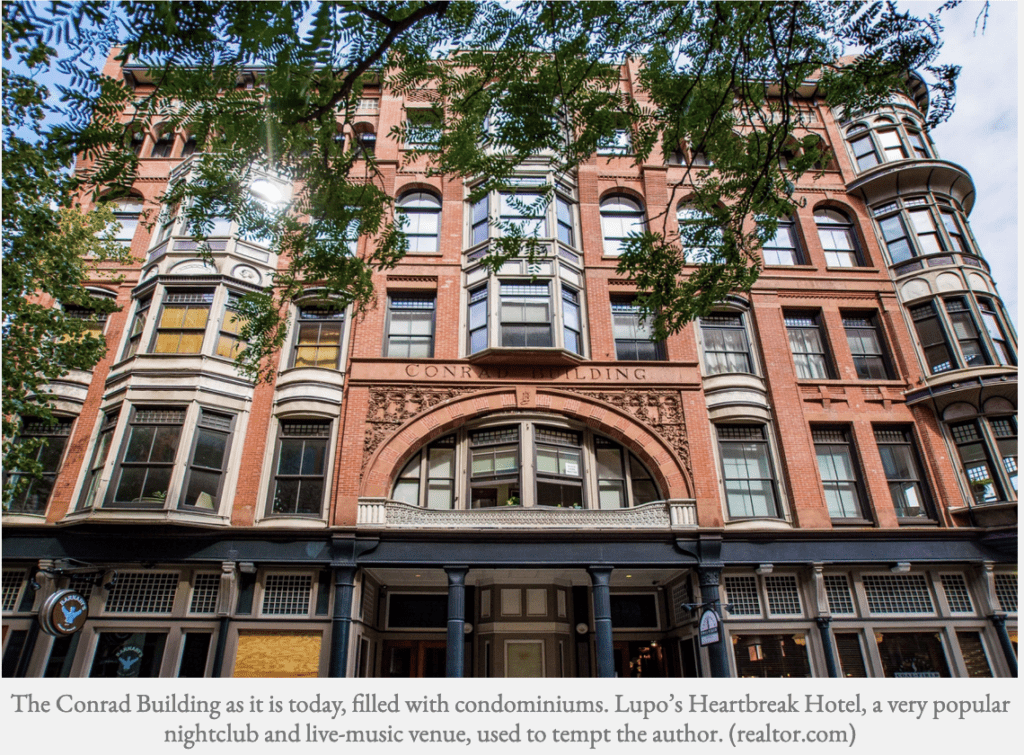

Between 1984 and 1999, I lived in three consecutive apartments on Benefit Street, 283, 395 and 372. Early on, just for kicks, I used to drive downtown at night, crossing the river, creeping down Westminster Mall, whose pedestrian sidewalks had been rolled up for the night. I would drive slowly, looking for “action” – something to gawk at, really, for I was a dweeb. Block after block, nothing but dreary men lurking in dreary doorways. Then, pay dirt: I would reach Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel, a live-music club in the old Conrad Building (1885) just before Westminster T’s at Empire. I would slow down (never any cars behind to rush me) and peer through Lupo’s open doors at the writhing, pulsating scene within. I’d never go in myself, at least not until the club moved next door to me after I moved into the Smith Building.

Lupo’s had been forced to relocate from the Conrad by the gentrification forces unleashed by Buff Chace. Rich Lupo moved his establishment, which included a smaller nightclub, just as noisy, called the Met Café, into the Peerless Building next to the Smith Building, where I was among the first tenants. I was writing about development issues for the Journal. Chace was my landlord; his projects were often the subject of my weekly architecture column. Chace had bought the Peerless to rehab as lofts, and a legal battle erupted between him and Lupo. Young metal-heads supporting Lupo’s and the Met accused loft dwellers like me of wanting downtown to resemble Barrington (a quiet, wealthy, dry town southeast of Providence known as Borington). Not so! Bad, bad, bad, bad vibrations! Eventually, Chace helped Lupo move his club yet again, into the Strand Theater a block away on Washington Street. (The Strand eventually went condo, too, in parts of the building not used by Lupo’s; I trust the condo buyers enjoyed the free live music.)

The Peerless, which had been a department store back in the day, opened in 2004 with ninety-seven units around a seven-story atrium, a sort of urban Peyton Place with a roof garden, where tenants, peering out into the atrium, could keep an eye on who was being entertained in who’s loft. Ah! City life!

This sort of churning captures the heart of a living city, indeed of life itself, the life well lived, you might say. Stasis is the status of a city in decline. Like every other active city, citizens confront what they perceive as parking and traffic problems. In fact, those who live or work (or both) in downtown Providence have relatively little to complain about in terms of where to park or how many red lights they must wait on before penetrating an intersection. Providence is at equilibrium, developmentally, which means that its comforts and discomforts are in relative balance. Unlike stasis, equilibrium implies pressure from both the forces that propel development and those that retard it. That is, in stasis there is nothing going on. In equilibrium it may still be very difficult to line up the permits and secure the finances necessary to move a project forward in Providence, but the conditions that provide incentives to do so push developers and entrepreneurs to persevere.

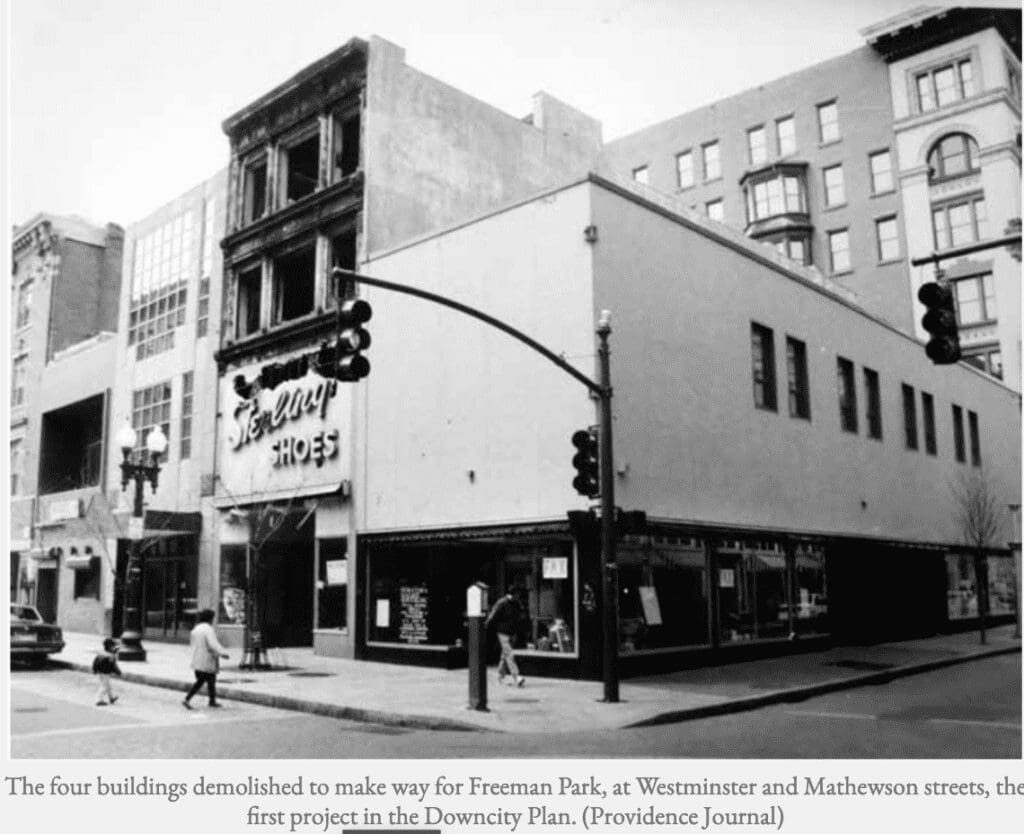

The first project under the Downcity Plan required, of all things, demolition. Four buildings were torn down at the intersection of Westminster and Mathewson streets, kitty-corner from the Tilden-Thurber Building (1895). Stanley Weiss’s office on its second floor today overlooks the project, now known as Grace Square. Its full name, Grace Square at Robert E. Freeman Memorial Park, [serves as the courtyard of Hotel Providence, also developed by Weiss] and honors the late Rob Freeman, a former director of the Providence Foundation. This group, an offshoot of the chamber of commerce, was the major instigator of the Capital Center and river relocation projects. Its board and its succession of directors, Romolo (“Ron”) Marsella, Kenneth Orenstein, Rob Freeman, Daniel Baudouin and Cliff Wood have been there for downtown, first and last, throughout its revitalization.

Overlooking Grace Park, Weiss had one of the best views in town once the four buildings were gone. The buildings were dilapidated. The only attractive one of the four had sustained heavy damage by fire but remained unrepaired. The corner looked like Beirut, the Aleppo of its day. No doubt the rents paid by its two tenants, a pizza joint and a private mailbox emporium, reflected its “sense of place.” The tenants were understandably reluctant to seek new digs, even with city assistance. Around the same time, Weiss evicted the Safari Lounge, a resolutely downscale bar, from another of his buildings nearby. The club sued, but lost. I thought the eviction showed poor judgment. In a January 30, 2003, column, “In defense of gentrification,” with the pre–revitalized downtown in mind, I wrote:

One can no more expect landlords to neglect buildings in perpetuity as welfare programs for struggling artists or buck-a-beer joints than one can expect those same tenants to embrace building improvements that will raise their rents. They whistle past the graveyard as the gathering clouds of renaissance darken, praying that their landlord fixes up all his other buildings before getting around to theirs.

There is a certain vitality to dark streets empty most nights until drunks stumble in a rowdy mass from clubs at 1 a.m. But it will be a sad day if City Hall ever determines that the preservation of this vitality should be the urban policy of Providence.

Thankfully, Providence has not sought to preserve its decline. it has even followed the New Urbanists’ advice, replacing a series of suburbanized one-way streets with two-way streets. Andrés Duany still reminds audiences that a historic district is nothing but a neighborhood built before urban renewal and modern zoning. The Downcity Plan has preserved the beautiful buildings of downtown but not the seedy lifestyle that prevailed after the dark clouds of urban renewal sent urbanity fleeing from downtown. Still, an old friend of mine visiting from our native Washington, D.C., deplored the disappearance from Providence’s downtown of its ubiquitous dives where you could get a drink for breakfast, and I could see his point. His father and mine were both city planners. They would have realized how difficult it is to find and then sustain a balance among the many competing aspects of urban life. This Providence has done.

The downtown of 2016 [or of 2023, for that matter] is not much different in appearance than the downtown of 1984, when I arrived. What is different is the little things. It is cleaner. There are more people. The faux façades are gone. There are more trees. Many streets are lined with period lampposts. It is amazing how much of a difference such lampposts, purposely designed to be beautiful, can make, and for a relative pittance of city funds. Hanging from the lampposts are flower baskets, installed in warmer months by the Providence Downtown Improvement District’s “clean-and-safe” teams, who also plant flower beds at strategic intersections and are, in general, specialists in “City beautiful.” They are also ambassadors on the street for visitors. The sum of all these little things is one big thing: there is more vitality.

The only constant is change – and it is vital that change be for the good, as judged by the people, not the experts.

[Yes, there are more ugly buildings that create a deplorable undertow in the flow of Providence development, but at least they have been kept out of “Downcity” – so far.]

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451.