Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Executive Order slams brakes on Offshore Wind – The Nantucket Current January 23, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Cider Glazed No. Atlantic Swordfish, Root Veggies, Brussels Sprouts January 23, 2025

- Little Compton, Newport, Scituate public water systems to address PFAs, drinking water quality January 23, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for Jan. 23, 2025 – Jack Donnelly January 23, 2025

- It is what it is: 1-22-25 – Jen Brien January 22, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

LOST Providence: Providence lost, regained II – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Photo: Postcard of Waterman Building (1893), RISD’s first permanent edifice. (RISD VR blog)

Editor’s note: This is the second of several sections of the epilogue to Lost Providence, first published in 2017. Further sections are upcoming soon.

***

The Rhode Island School of Design offered its services [a decade ago] to assist the I-195 commissioners in producing a successful design template for the 195 land. To shape its guidance, RISD should touch base with its origins. The school was formed in 1877 to soften and sweeten the local manufacturing process. As set forth in its original bylaws, its first goal was to foster “[t]he instruction of artisans in drawing, painting, modeling, and designing, that they may successfully apply the principles of Art to the requirements of trade and manufacture.”

At a time when Rhode island was competing with the world in a range of light and heavy industries, RISD may have been more instrumental in the state’s prosperity than it realizes today. For a century, the state’s private sector accomplished manufacturing miracles in mills of brick that housed the latest technological advances. it was only toward the middle of the twentieth century, as the high cost of doing business in Rhode Island sent more and more plants south, that Rhode island industrial leaders – and RISD – embraced a very bad idea.

The bad idea was that the machine age requires a machine architecture. Reformers of architecture a century ago had toyed with basing building design on the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. They did an about-face and embraced the “form follows function” credo. The meaning of the term was vague to begin with, and it was botched in practice. The world got architecture conceived as a metaphor for the machine but without the efficiency promised by machinery, let alone in a form that might have made the absence of efficiency more bearable.

This train of thought originally came to me from Nikos Salingaros, a mathematician and architectural theorist based at the University of Texas and the author of Anti-Architecture and Deconstruction: The Triumph of Nihilism and other books. working with the architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander and others, Salingaros has also done research linking most people’s preference for traditional architecture to neurological patterns in the human brain. The thinking, briefly, is that the widespread allure of ornament and detail in architecture comes from the prehistoric defense mechanisms of humans. For primitive man, the more information, the better. To see, and to recognize in a split second, the shadow of the head of a lion against a rock near a tree was a matter of life or death. Today, survival mechanisms have evolved considerably, but the love of ornament stands in for cues of visual perception on the full range of scales that long ago served to sustain the individual and, ultimately, the species.

Many others are researching the relationship between the human brain and the widespread skepticism toward experimental architecture and the preference for traditional buildings and public spaces.

In a 2006 essay on the relationship between music and architecture, “La Violon d’Ingres” (The Violin of Ingres), Steven Semes, a professor of architecture at Notre Dame and author of The Future of the Past (2009), writes:

Scientists are interested in pattern and proportion once again. Neuroscience is beginning to reveal ways in which pattern recognition is built into the complex and subtle mechanisms of the brain. From this viewpoint, classical architecture and music are analogous, not just because they reflect one another but because they reflect us and the way our minds work. It should come as no surprise, then, that both music and architecture today are engaged in retrieving their respective traditional languages: melody, tonality, proportion, ornament, the classical orders – the whole lot.

Governors and mayors may well be disinclined to muck around in neurophysiology, and who can blame them? But there are other reasons why developers should prefer traditional to modern architecture.

On the agenda of most architects, and governors, today is climate change, with developers and architects seeking to reduce their projects’ carbon footprints. Buildings account for 39 percent of annual carbon dioxide emissions in the United States. Weaned on cheap oil before its risky environmental impact became evident and its low cost evaporated, the architecture of the Thermostat Age cannot do much to soften its negative impact on climate. Replacing an old building with a new one piles up an insurmountable carbon deficit even before adding in the high cost of operating complex systems in new buildings, the inefficiency of driving ever farther to work in petroleum-based vehicles or the new buildings’ short shelf life – planned obsolescence, the half-sister of demolition by neglect – often less than a half or a third the life of a traditional building, requiring multiple replacements over time.

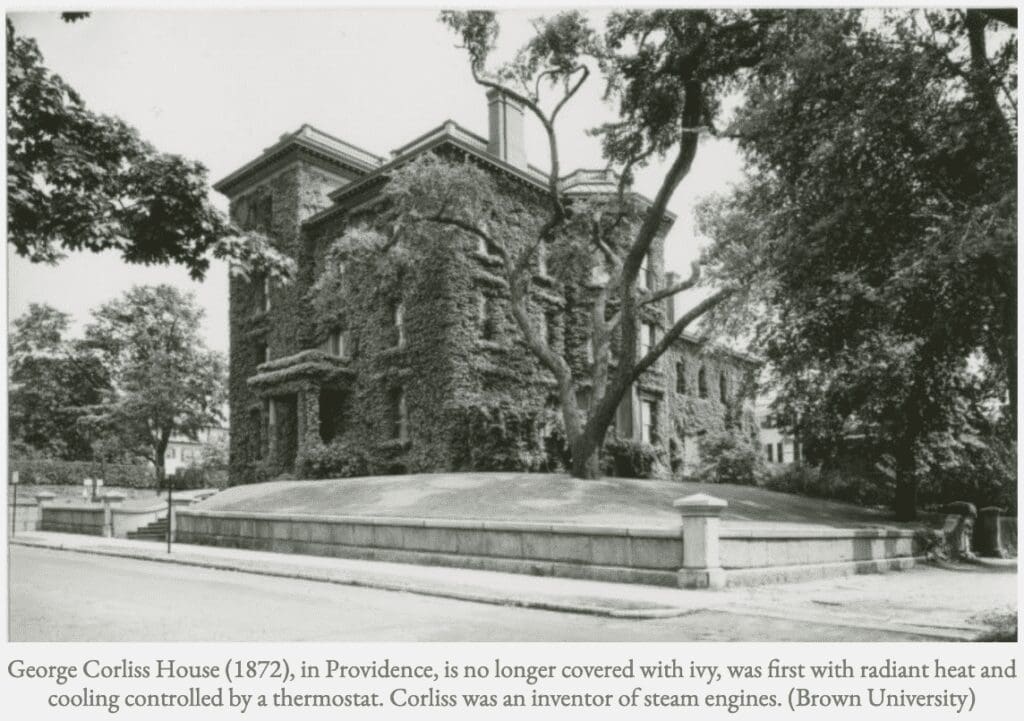

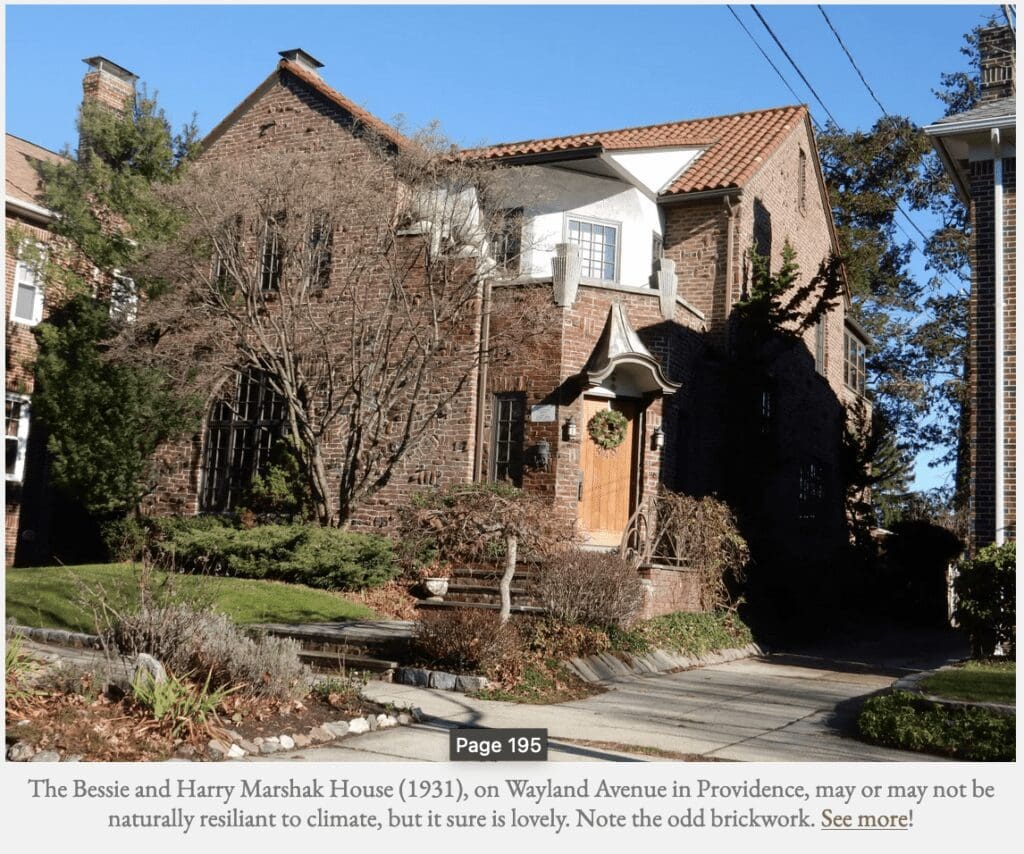

Buildings erected before the Thermostat Age are intrinsically more sustainable than are modernist buildings. Before oil and electricity, buildings used many natural strategies to address the challenges of climate. Depending on region, they had thick walls or thin walls to retain or disperse heat or cold; high ceilings or low ones for the same purpose; roofs designed to shed rain and snow; porches, courtyards, awnings, shades, shutters and windows that open and close to regulate light and shade; ceiling fans for cooling in summer; fireplaces for heat in winter; site placement to harness the seasonal angle of the sun or the breeze; landscaping to enable trees to provide shade and oxygen as well as beauty; and so many more features, including natural materials locally sourced. Builders enlisted the help of Mother Nature to regulate the environment within houses and other buildings.

All of those climate-friendly features are still in use today wherever older houses and buildings survive, and are available for use wherever new traditional buildings are sold. These natural efficiencies do not require us to go “back to the future.” They can make our comforts better, more durable and more affordable.

The manufacture of architecture will change as beauty resumes its role as a factor of production. Man-made materials can often bridge the gap between current design practices and the design practices of the future, which will see natural materials become more affordable. Advances in fabrication will be especially useful to marketing as high technology continues to reduce the cost and increase the capacity of machines and computers to create ornament and other architectural detail from matter such as wood, stone, precast concrete or plastic.

So, governors are free to ask developers to pitch in against climate change by proposing projects that feature natural strategies to reduce carbon emissions. Most of those strategies will cause buildings to look more traditional – more natural – and this will make even large development projects easier for the public to swallow.

***

The next section of the epilogue from Lost Providence will appear in the next post on this blog.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451.