Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Detailing Manhattan: Christopher Gray’s Legacy – David Brussat April 26, 2024

- Business Beat: BankNewport supports Kids’ Zone at new Save The Bay Hamilton Family Aquarium April 26, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 26, 2024 – John Donnelly April 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: Dread. Fear. Welcome relief. – Mari Nardolillo Dias April 26, 2024

- Outdoors in RI: big animals, tiny Ticks, huge Trout, Chepachet’s Harmony Railway, 2A – Jeff Gross April 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

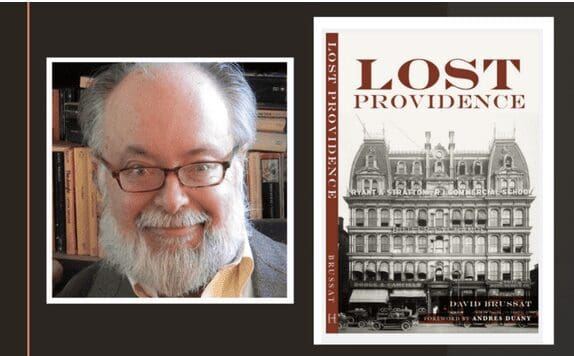

LOST Providence: Providence lost and regained – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Editor’s note: This is the first section of the epilogue of Lost Providence, entitled “Providence Lost, Providence Regained.”

The purpose of the D-1 District is to encourage and direct development in the downtown to ensure that: new development is compatible with the existing historic building fabric and the historic character of downtown; historic structures are preserved and design alterations to existing buildings are in keeping with historic character.

This passage from Chapter 513, Article 6, section 600 of the Providence Zoning Code, passed in 2014, is the law that protects historic character in downtown. It carries forward language similar to that of local zoning codes reaching back many years. Of course, wording such as “compatible,” “in keeping with” and even “historic character” is subject to interpretation. The existence of an unsympathetic building or two in a historic district can, in theory, be used to justify another unsympathetic building. Still, in the district encompassed by the Downcity Plan, almost no new construction, additions or alterations out of character with downtown’s historic appearance – as the average person would interpret the words – have occurred since the 1980s. That is in step with the unofficial moratorium on building demolitions that prevailed, with few exceptions, between 1979 and 2005, a period that encompassed at least three bona fide building booms.

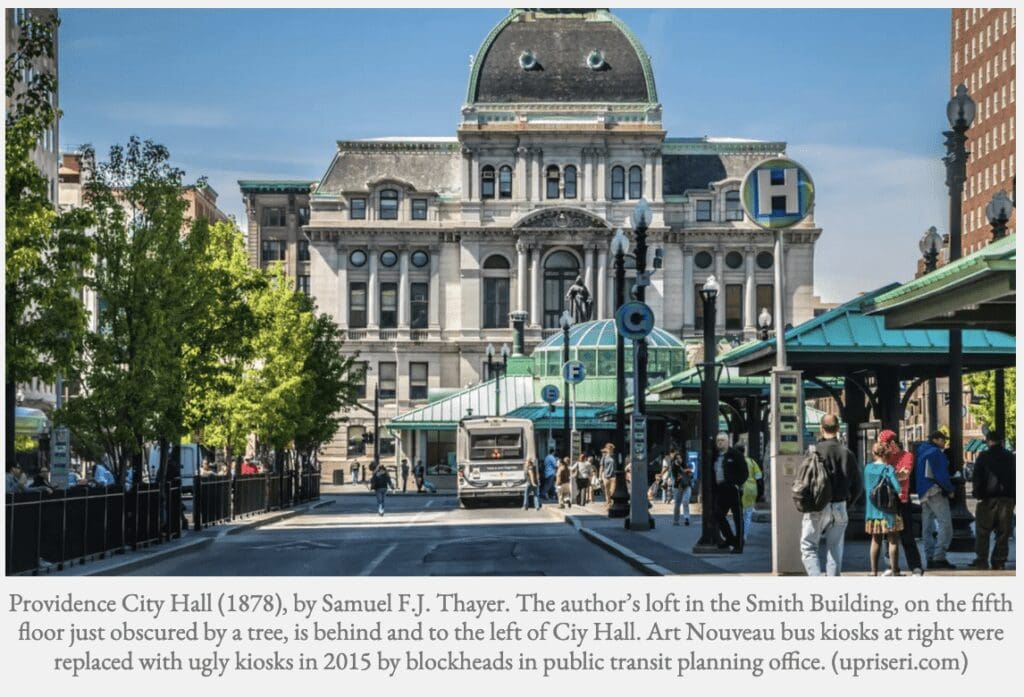

Providence City Hall (1878), by Samuel F.J. Thayer. The author’s loft in the Smith Building, on the fifth floor just obscured by a tree, is behind and to the left of Ciy Hall. Art Nouveau bus kiosks at right were replaced with ugly kiosks in 2015 by blockheads in public transit planning office. (upriseri.com)

Thus it might seem that Winston Churchill’s “We shape our buildings; thenceforth they shape us” – the quotation at the beginning of this book – has in some inchoate manner guided development in Providence. An enactment of law speaks with force, the more so when it has been honored not in the breach, as have so many, but by intelligent observance over decades.

The city carried out very little of the Downtown Providence 1970 Plan. In 1960, when that plan was announced, laws defending downtown’s historic character had not been enacted. And yet it was observed by the city as a sort of intuitive municipal credo. Only thereafter did modern architecture’s rise call for a defense of historic character in the language of the law.

Although welcome signs such as “Beautiful Rhode island” and “Historic Providence” still stand alongside the major highways into the city and state, the Ocean State has recently struggled to update its “brand” to replace earlier logos and mottos emphasizing the state’s beauty. The need for such campaigns is debatable. Visitors travel to Rhode Island on vacation, and organizations schedule meetings in Providence and Newport because the state’s beauty and historical character are widely known commodities. That fact has little to do with branding campaigns. Still, the campaigns do suggest that officials have long understood that beauty is vital to the state’s health and well-being.

View to west from Van Leesten Pedestrian Bridge of I-195 “Innovation District.” (Steve Kroo video)

Now, in its effort to develop land near downtown Providence vacated by the relocation of Route 195, the state seems to have suffered a massive brain fart, causing it to overlook the importance of beauty. Already, although progress in redeveloping the I-195 land has been slow, Johnson & Wales has just opened the district’s first building, a new modernist facility to house its engineering and design department. Other plans for new “high- tech” buildings in this corridor are in early stages of design development, with three newly proposed towers of high-tech design in prospect [just recently ditched]. An “innovative” engineering school facility at Brown University is also under construction on College Hill. All of this promises to undermine Rhode Island’s brand – if not the official brand, whatever that is at this stage, then certainly its longstanding natural brand promoting the state’s beauty and historic character.

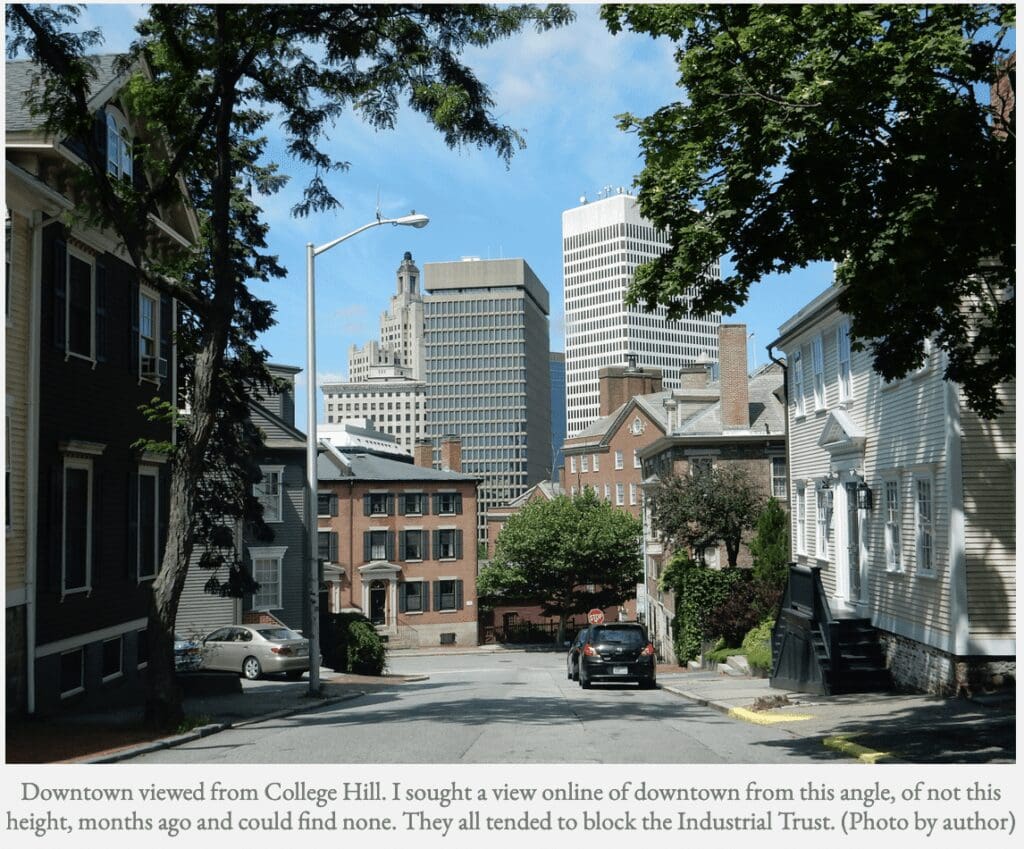

Downtown viewed from College Hill. I sought a view online of downtown from this angle, of not this height, months ago and could find none. They all tended to block the Industrial Trust. (Photo by author)

The current governor, Gina Raimondo [now Daniel McKee], should phone all the developers involved to urge them to revise their plans in ways that will strengthen rather than weaken the state’s brand, its beauty – a major competitive advantage it has over other states. Under Section 603 of the zoning code, the I-195 Redevelopment District Commission can offer development incentives. “The purpose of these incentives,” the code states, “is to encourage development that will be compatible with the character of downtown and carry out the goals of the comprehensive plan.” The governor can advise developers of the existence of such incentives. [He] can also remind them of the protections for historical character in section 513.6.600 of the zoning code and note that the state prefers initiatives that strengthen rather than undermine the competitive advantage embodied in such laws.

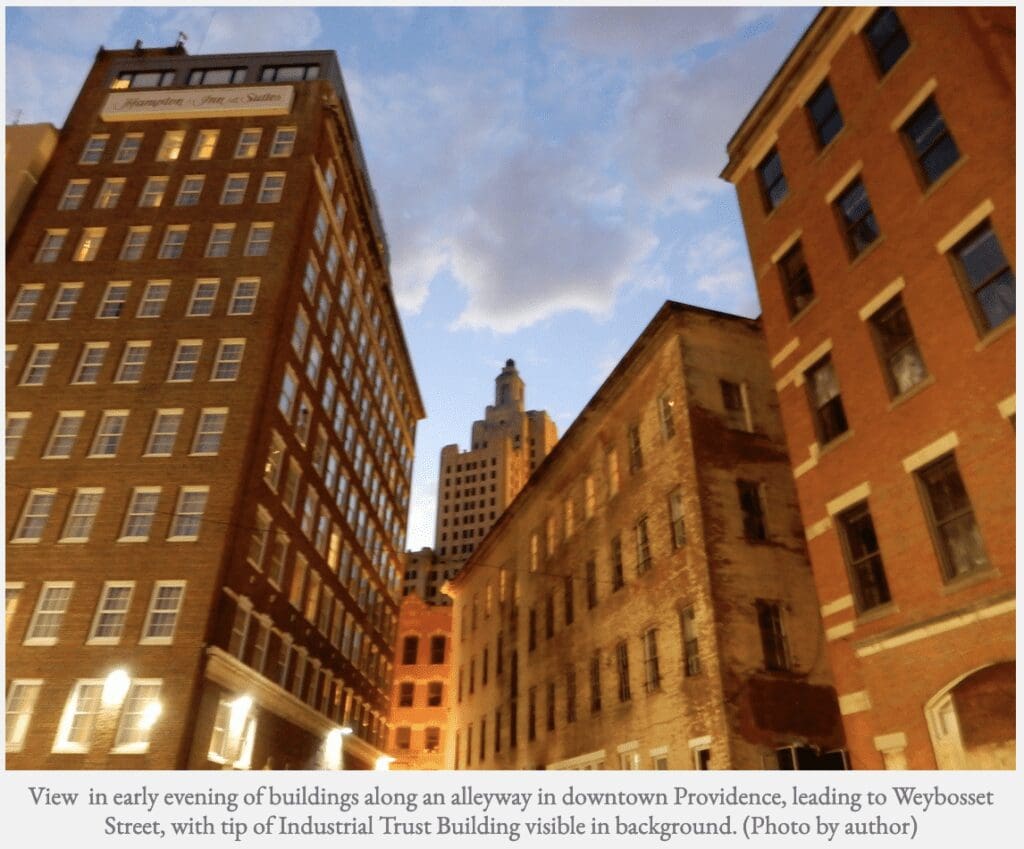

View in early evening of buildings along an alleyway in downtown Providence, leading to Weybosset Street, with tip of Industrial Trust Building visible in background. (Photo by author)

In the lax design environment that has shaped development in Providence in recent years, officials may be understandably reluctant to even appear to “mandate” design. The bill that in 2011 created the I-195 Redevelopment District, and the commission managing its build-out, took as their model the Capital Center Commission, which was “reticent about mandates to architectural expression.” With the conflicting results of that reticence in mind, the I-195 commission should not hesitate to express a preference for buildings that strengthen rather than weaken the state’s brand.

After he took office in 2014, Boston’s new mayor at the time, Marty Walsh, gathered that city’s developers together to urge them to propose “bolder” new buildings. His advice may have been dodgy, too inclined to abet the further erosion of historic character in the Hub, but he was not “mandating” style. He was using his bully pulpit to encourage his idea of better development in Boston.

Rhode Island leaders such as Gina Raimondo, Governor McKee, and Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza [and recently elected Mayor Brett Smiley] should do likewise. That’s their job. They may find that developers are more eager to have state and local government on their side than they are to stamp their proposed developments with this or that statement of aesthetic design.

***

The next blog post will reprint the next section of the epilogue to Lost Providence.

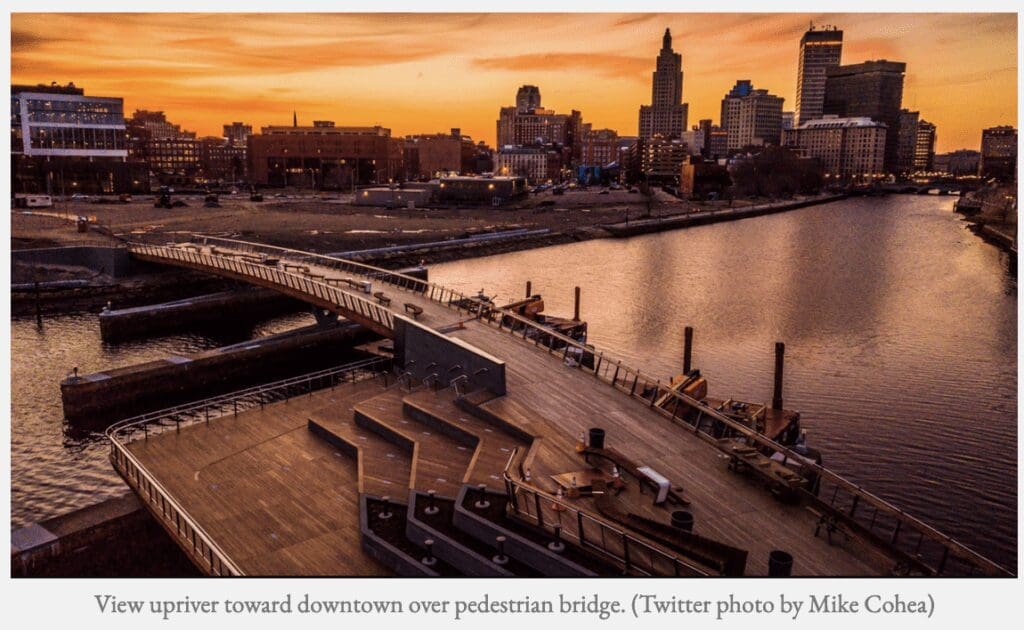

View upriver toward downtown over pedestrian bridge. (Twitter photo by Mike Cohea)

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451.