Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Executive Order slams brakes on Offshore Wind – The Nantucket Current January 23, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Cider Glazed No. Atlantic Swordfish, Root Veggies, Brussels Sprouts January 23, 2025

- Little Compton, Newport, Scituate public water systems to address PFAs, drinking water quality January 23, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for Jan. 23, 2025 – Jack Donnelly January 23, 2025

- It is what it is: 1-22-25 – Jen Brien January 22, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

LOST Providence: Lost, regained, part IV – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Photo, top: R.I. State House plays Providence City Hall in 2007 film “Underdog.”

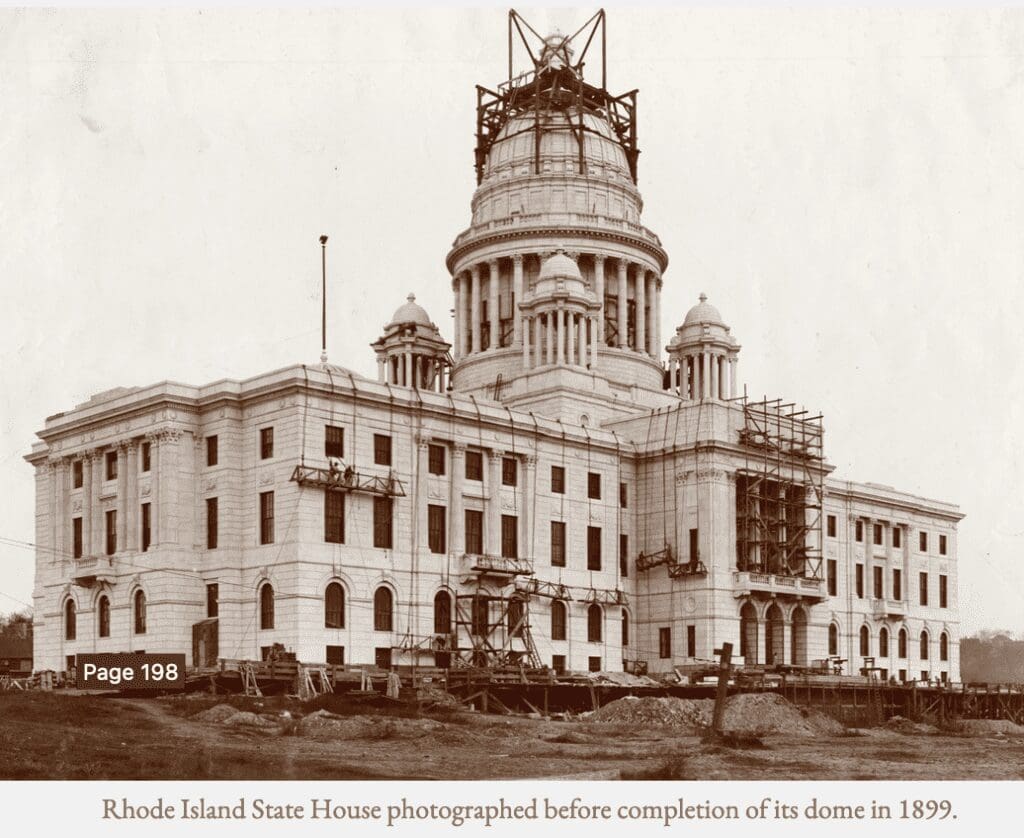

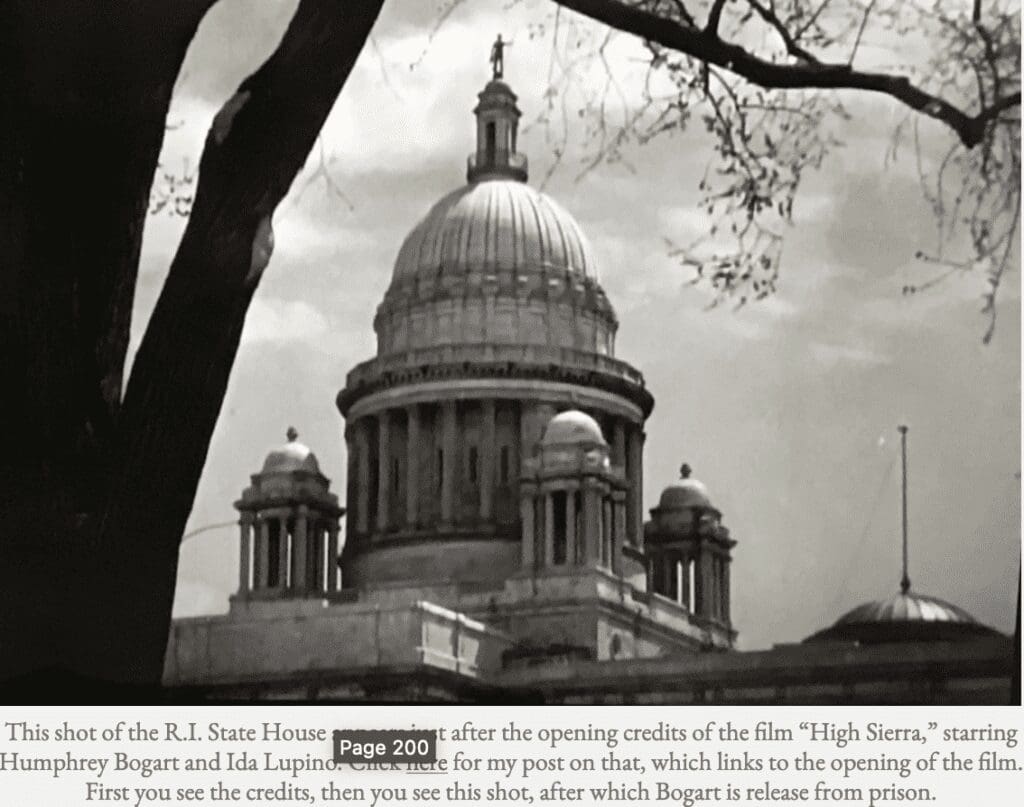

Editor’s note: This is the final segment of the epilogue of my book, Lost Providence, entitled “Providence Lost, Providence Regained.” Published in 2017, the book is a history of the design of the modern-day capital of Rhode Island, specifically of its downtown. So why is this reprinted segment illustrated by the Rhode Island State House rather than the City Hall of the state capital? Partly because I wanted to include a little “cherry on top” for readers who have made their way through this reprint of the second half of the book, called “Part II” and having to do with the major development projects that created the city’s downtown. The final photograph links to a segment of the film “High Sierra,” with Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino, which contains a surprise for Rhode Islanders.

***

This book addresses change as the only constant and tracks its progress in Providence. But it challenges ideas that privilege only big change, leaving small, manageable change in the lurch. This book challenges those failed ideas everywhere they prevail. Providence’s success in revitalizing itself proves that—not withstanding Daniel Burnham’s “Make no small plans!” – it is not the size of the plan but its beauty that counts. Beauty is a free gift to every level of society, a sort of art museum with no charge wherever a street of lovely buildings exists, and perhaps most sincerely appreciated by those least fortunate. The future is not about trying to copy the past or keep up with the Jetsons. Tradition is not just about the past but about the steps we take to progress into the future – the traditions of tomorrow. Moving society into the future isn’t about reconceptualizing everything we know until we overtake our capacity to understand it. That is where we stand today in many fields, but most visibly, most egregiously, in the field of architecture. The future is part of a millennial continuum held hostage by modern architecture in a mere sliver of time. That can change, too.

Providence and Rhode Island are uniquely positioned to raise the status of beauty and tradition in architecture, just as many people are striving to do in the field of cuisine. Architecture and food are flip sides of the same coin:

What would our dinner tables look like if culinary culture were half as hung up on the rigid rulebook of progressive aesthetics as architectural culture is? Would we be allowed to eat bread or rice, or would they be forbidden due to their unspeakable antiquity? Would regional fare using locally harvested ingredients be celebrated as part of a rich, diverse, interconnected world of unique traditions, or would it be condemned as provincial nostalgia?

The passage is from an essay by Nathaniel Robert Walker, a professor of architectural history at the College of Charleston. In “From the Ground Up: How Architects Can Learn from the Organic and Local Food Movements,” he notes that by the 1950s processed food had become America’s dominant cuisine, much as processed architecture is dominant in America (and elsewhere) today. Change for the better in food came because people at every point in the food chain got fed up, so to speak, with the status quo. From the bottom up, the slow-food movement has challenged the agricultural establishment and its downstream confederates, Big Food and Big Grocery, with some success. Big Architecture can be reformed, too. It may not be as delicious, but it can be more fun.

Reform of our built environment will also be a bottom-up process. It can be a movement. It can start with activists clamoring for change at design-review meetings. It can start with civil disobedience, with a sit-down protests in front of a bulldozer on the Brown campus. It can start with a rock propelled at night through the plate glass of a glass box. (Who inserted that line?!) It can start in a state with the DNA of revolt in its history. It can start with a governor who wants to carve out a place in that history. It can start in Rhode Island.

***

This is the final segment of the epilogue of the book Lost Providence, published in 2017.

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451.