Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 19.06.25 (Military Funerals, Job Fair, Benefits, Events) – John A. Cianci June 19, 2025

- East Providence First in U.S. to Equip All Firefighters with PFAS-free Gear June 19, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Saffron Bouillabaisse with Tarhana Lobster Jus June 19, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 19, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Lincoln vs. Jefferson, architecturally speaking…

Photo: The Jefferson Memorial, by John Russell Pope, on the Tidal Basin. (Wikipedia)

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

A comparison of the Lincoln and the Jefferson memorials is almost as fascinating, in some ways even more so, than a comparison of Messrs. Lincoln and Jefferson themselves. Since I can add little to the second conversation I will confine myself, on this Independence Day, to the first.

For reasons that will become clear, I am not including Washington’s nearby commemorative obelisk in this analysis of our dear nation’s most sacred monuments. Washington is the father of our country, while Jefferson and Lincoln, both beloved, still vie for No. 2 in the ranking of presidential fame. But their rivalry is not the reason their monuments are discussed herein.

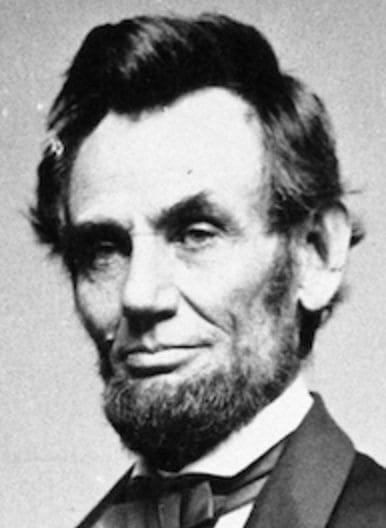

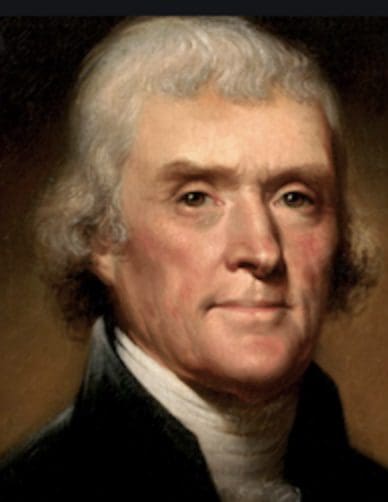

The Lincoln Memorial honoring our 16th president, Abraham Lincoln, heroic preserver of the Union, was completed in 1922. The Jefferson Memorial, honoring our third president after Washington and Adams, a founder of our nation and of the Democratic-Republican Party, and, of course, author of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, was completed in 1943. The design of Lincoln’s monument by the classicist Henry Bacon as a Greek temple was largely uncontroversial after the proposal for a more modest design, supposedly more in keeping with Lincoln’s character – a log cabin (much smaller, it may be presumed, and not of wood) – was rejected. Few changes to the original design were proposed. The statue of Lincoln by Daniel Chester French was doubled in size from 10 feet to 19 feet, so as to better fill the massive interior.

The Lincoln Memorial arose at the west end of the National Mall, beyond a long, rectangular reflecting pool. Lincoln’s monument takes pride of place over Jefferson’s, which is sited on the far side of the Tidal Basin across the Mall from the White House. The two axes cross midway at the Washington Monument. But it is the Jefferson Memorial whose design sparked a battle royal that, so far as I am aware, no prior design of presidential memorials featured. That battle pitted heroic classicism against a then-upstart, tradition-averse modernism.

The Jefferson Memorial’s architect, John Russell Pope, made reference in its circular design to the Roman Pantheon and to Jefferson’s own design for the University of Virginia – especially the library, known as the Rotunda, that sits at the head of the “academical village” and Lawn, with its parallel formation of diverse classical pavilions. Pope in 1941 completed the National Gallery of Art in a stripped classical design – tradition’s response to the rising challenge of modern architecture – perhaps the last major federal building of classical design in the nation’s capital until the huge Ronald Reagan Building in 1998, completing the massive Federal Triangle project. The plan for a memorial to Jefferson was a late addition to the Federal Triangle plan, most of whose 10 classical buildings were complete by the mid-1930s.

Pope’s classical proposal for the memorial to Jefferson raised a fury among modernists, who were just then beginning to subvert tradition as the backbone of architecture in the United States and Europe. The U.S. Commission of Fine Arts opposed the design from the start, never granting approval, which thankfully was merely advisory. Women chained themselves to cherry trees on the site. Pope listened in silence as his design was criticized as “a tired architectural lie” using “styles that are safely dead.” William Hudnut, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, who had hired founding modernist Walter Gropius to teach and had destroyed the GSD’s famous collection of classical plaster casts, regretted that Pope’s design failed to provide an “abstract and universal expression in art.” He added:

In spite of Jefferson’s sympathy for the classic, shall we commemorate his simplicity and reticence by the most grandiloquent and splendiferous of monumental forms, his devotion to American culture, his democratic sympathies by an Imperial utterance?. … [It] will embody so grotesque a presentation of Jefferson’s character as to make him – if such a thing is possible – forever ridiculous.

Ridiculous. But not nearly as ridiculous as current denunciations of President Lincoln and President Jefferson.

I love the Jefferson Memorial’s graceful, calming, rondurous form. Even more I love wandering through the Lincoln Memorial’s interior spaces, gazing up at Honest Abe and viewing the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol down the corridors of the colonnade that surrounds the building. As a youth I would sit by myself on its broad steps and contemplate the city planned by Pierre L’Enfant. His plan still undergirds its historic urbanity. I once sat in on a Fine Arts Commission meeting at which the design by Providence’s own Friedrich St. Florian of the National WWII Memorial was almost pecked to death by ducks. Fortunately, the ducks lost. The memorial sits discreetly today between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, widely beloved by veterans.

Fortunately, as well, the president presiding over the Jefferson Memorial design deliberations was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He stepped into the fray and ordered by fiat that Pope’s original proposal be completed. It was built, and dedicated in 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth. Poor FDR. By the time his turn came around for a memorial of his own on the Mall, the modernists were powerful enough to ensure that it was modernist. While successive modernist proposals became less obnoxious over a span of almost four decades, the completed memorial, which opened in 1997, is dismal, a relatively mild precursor to the warts-and-all philosophy currently dragging down our national spirit. As they say, no good deed goes unpunished.

_______________

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/