Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

How modernism got square – David Brussat

Editor’s note: Here is a post from December 2013, almost a decade ago, shortly after the Providence Journal booted my Journal blog from its roster of staff-written web logs, which is where the word “blog” comes from. I used to write two or three of these per day, even while I was also writing editorials and my weekly column. Maybe that is why the Journal put a stop to it.

The title of this post harks back to one from this blog’s Providence Journal days, when I linked to a long piece in Metropolis magazine by Michael Mehaffy and Nikos Salingaros, and then did a column about it called “How modern architecture got square.” Now a piece by Robert Adam, the British classical architect, approaches the same issue from a different direction. It is called “The Institutionalization of Modernism,” in his blog at Building magazine, published in the U.K.

[Adam’s article is here.]

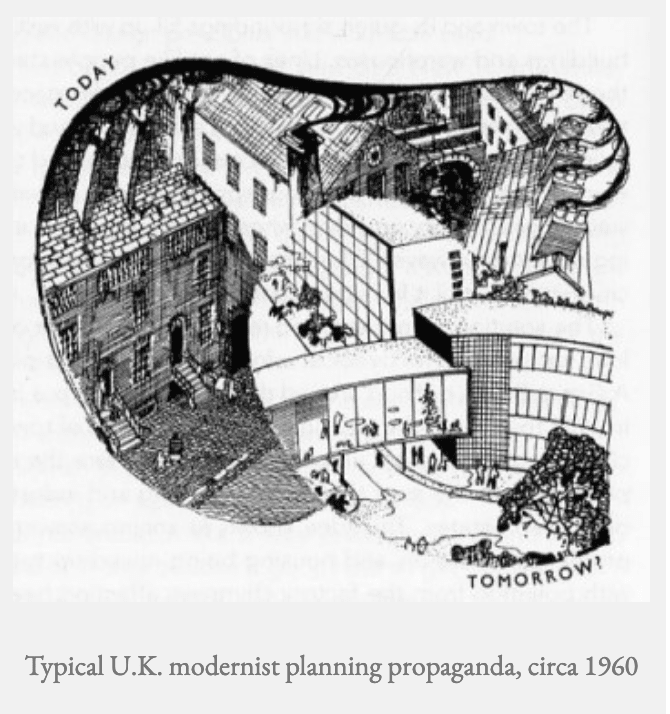

The piece follows Adam as he rifles through a series of official British planning documents going back years, which trace the growth of language in planning regulations there that force planning officials to favor modern rather than traditional architecture.

Planners in Britain must adhere to national planning policy summed up in official documents since passage of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. The latest version of the document, which he describes as “quite good,” states: “Planning policies and decisions should not attempt to impose architectural styles.” Maybe so, but a lot of official policy in prior years had similar language yet nevertheless favored or even mandated modernist styles, whether the wording of the rule stated so expressly or hinted it. (In bureaucracies, hints are often hazardous for lower-level officials to ignore.)

One example comes from planning regulations in two historic towns, Winchester and Chester. In Winchester, planners must abide by language that reads: “New development should complement but not seek to mimic existing development and should be of its time.” The first part sounds sensible to the average citizen, but the code words of “mimic” and “of its time” suggest very straightforwardly to planners that modernism is to be favored. Regulations in Chester beat even less around the bush: “The boldest and most successful designs are those which clearly express the ethos to which they relate, and do not refer to the language of earlier periods.”

In his piece, Adam describes planning language widespread in planning documents that may seem unobjectionable to many but is interpreted with great specificity as pooh-poohing new traditional designs by those charged with carrying out the law.

Adam concludes: “This is all part of the creeping institutionalisation of modernism. For half a century it has been the style of the architectural establishment. It is now becoming the style of the bureaucrats.” That’s bad news, but Adam hopes that Britons who want to rescue their built environment from modernism will send him examples from their jurisdictions that can be used to illustrate today’s reality and thereby encourage top planning authorities to even the playing field.

“I have spoken to the government’s chief planning officer,” advises Adam in a note to readers who want to join in the fun, “and he [is willing] to receive [letters] on the subject. [They] will need to be very cool and factual.” Well, readers, I guess that means it’s up to you!