Search Posts

Recent Posts

- The Real Housewives of Rhode Island coming to Ocean State May 8, 2025

- Homeless in RI: 2,000 homeless children – RFPs – May issue of Street Sights, by and for homeless May 8, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for May 8, 2025 – Jack Donnelly May 8, 2025

- New CEO of RI Community Food Bank will be Melissa Cherney, CEO, Great Plains Food Bank, ND May 8, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 08.05.25 (medical coverage, disability, news, events) – John A. Cianci May 8, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

UPDATED: Homeless in RI: Children, go where I send you…

“Children, go where I send thee” is a traditional African-American spiritual song, known this time of year as a Christmas carol.

The temperature in Providence is 25 degrees. It feels like 11.

Are there homeless children living on the streets? Rhode Island doesn’t really know. Officially. However, the recent homeless crisis on the steps of the Rhode Island State House has raised the question in an urgent way.

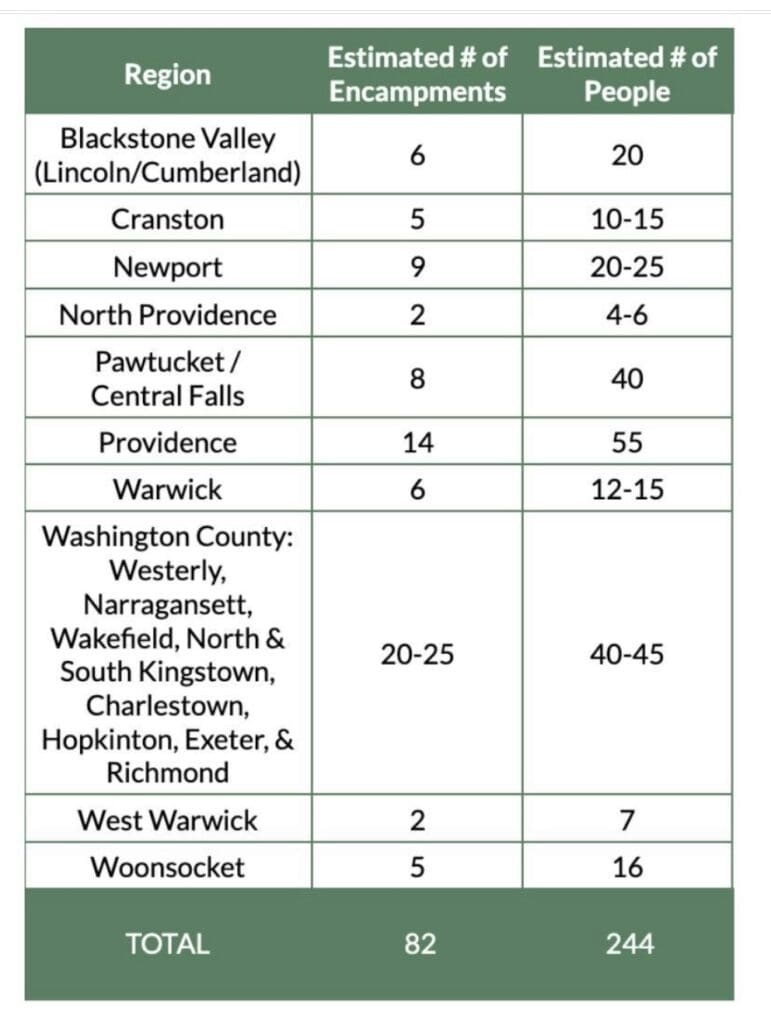

The state has asked for a specific location list of the “82 encampments” of homeless people that advocates say exist throughout Rhode Island. Advocates have been hesitant to provide that to the Governor’s office, saying instead that they would drive them to the encampments in an escorted tour, of sorts.

One reason encampments are under the radar is, according to advocates, is parents’ fear that their children would be taken away from them if officials knew how they were living. In news reports from the day at the RI State House when advocates and homeless walked the halls chanting, “Shame – shame – shame!” at people in the building, demanding to see the Governor, at least one family noted that fear; also saying that they wanted to get housed to ‘get their children’ back.

What does DCYF say?

We asked the RI Department of Children, Youth & Families (DCYF) if they had engaged with any families with children living outdoors, noting the reports mentioned by homeless advocates about the fear that parents who are homeless said they have.

We received this statement back: “DCYF is aware of [this] newspaper article and quote. Due to confidentiality laws, the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth & Families cannot confirm or deny whether a family has any involvement with the department.”

We then posed a hypothetical to the department asking them what their policy is if it is learned children are living outdoors, particularly in harsh winter weather. Their response:

“DCYF recognizes that with limited resources many families are finding themselves in unstable living situations through no fault of their own. Homelessness, alone, when parents have made attempts to resolve the situation, does not constitute child maltreatment. In these instances, families are referred to our community partner agencies for supports. A child who is experiencing maltreatment who is also homeless would be subject to a CPS investigation to address the maltreatment allegations.

DCYF and its service providers make efforts to assist the family to address their living situation. In 2022, so far, DCYF has assisted more than 60 families by providing funding for lodging in extended day hotels. Presently the Department has more than 30 families temporarily housed in such hotels.”

Inadequate Shelter for Children

The DCYF Standards for Investigating Child Abuse and Neglect (CA/N) Reports policy includes Inadequate Shelter as a definition of a child abuse and neglect allegation that the Department would investigate. That language is noted as follows:

DOP 500.0025 Standards for Investigating Child Abuse Reports

25. Inadequate Shelter

a. Failure by the parent/caregiver to provide or seek to provide shelter which is safe, healthy, and sanitary and which protects the child from the weather conditions, and/or other risk situations.

b. To indicate this allegation, one of several types of evidence is needed:

i. confession of caregiver;

ii. observation by or findings of a child protective investigator, law enforcement or medical professional;

iii. witness statements;

iv. statement of victim.

–

___

Homeless Children in Rhode Island

The Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness says that as of Nov. 30 there were approximately 615 people, including children, living in places not meant for habitation while they waited for spaces in shelters.

RI KIDS COUNT

In the report by RI Kids Count for 2021, they list data for Rhode Island families awaiting shelter:

• Shelter is not guaranteed and often not available due to capacity limits, and Rhode Island is not a right to shelter state.

• As of November 16, 2021, 1,013 Rhode Islanders were seeking shelter. Almost half (45%) of the people waiting for shelter were in families with children, and 267, or more than one-quarter (26%) were children under the age of 18.

• From October 8 – November 6, 2021, 574 Rhode Islanders slept outside or in their cars for at least one night, and 156 were in families with children. Almost half (44%) of the adults in these families with children had no income. During that 30-day period, 62 children under the age of 18 slept outside or in their family’s car for at least one night.

__

Rhode Island’s Annual Point-in-Time count

Each year homeless advocates conduct a point-in-time count of people experiencing homelessness on a single winter night.

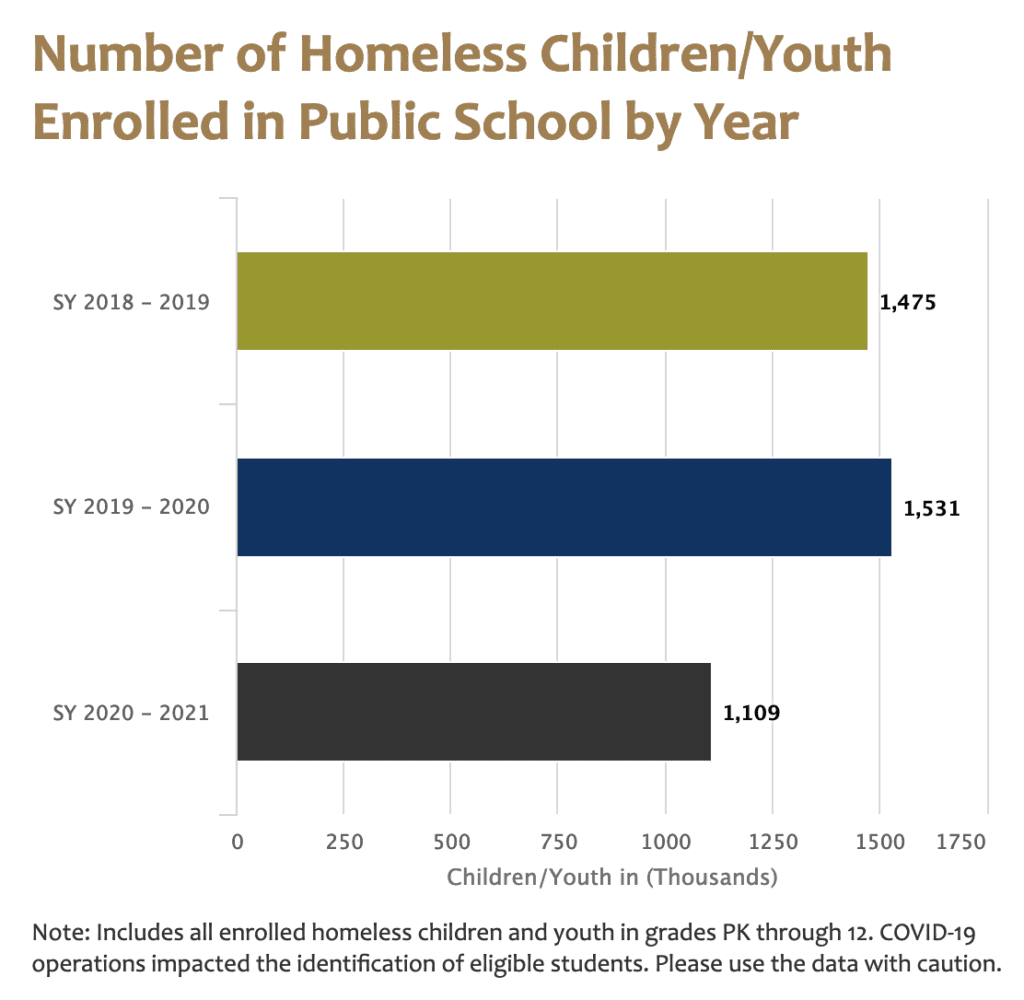

The January 2021 count showed a dramatic increase in people experiencing homelessness, including a 26% increase in households with children (from 121 in 2020 to 153 in 2021).

In Rhode Island in 2020, 3% (114) of the 4,029 indicated allegations of child neglect were associated with inadequate food or shelter.

Recommendations of the Point-in-Time study were several, noting that “addressing families’ housing needs can reduce child neglect and abuse and help families stay together.” – the final point on their recommendations was: “Fill the position of Deputy Secretary of Commerce and Housing to oversee housing initiatives and develop a statewide housing plan.” This position was filled by Josh Saal, known informally as Rhode Island’s “housing czar”.

In Massachusetts:

In 2020, Massachusetts had the 3rd highest rate of family homelessness in the United States. 2,343 children are the estimated number of homeless children in Boston on any given night. This is enough to fill Boston Children’s Hospital five times. 65% of children admitted to the emergency room have a diagnosis of homelessness.

In Los Angeles:

This week Karen Bass was sworn in as the new Mayor of Los Angeles. In her campaign she promised to declare a state of emergency for the city’s homelessness crisis. It is estimated that 17,000 people live homeless in the city. 5 people die each day. Without a winter weather crisis. In her acceptance speech, Bass promised to keep her promise to declare the state of emergency and noted “we must have a single strategy bringing together government, the private sector and other stakeholders” to address the crisis.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

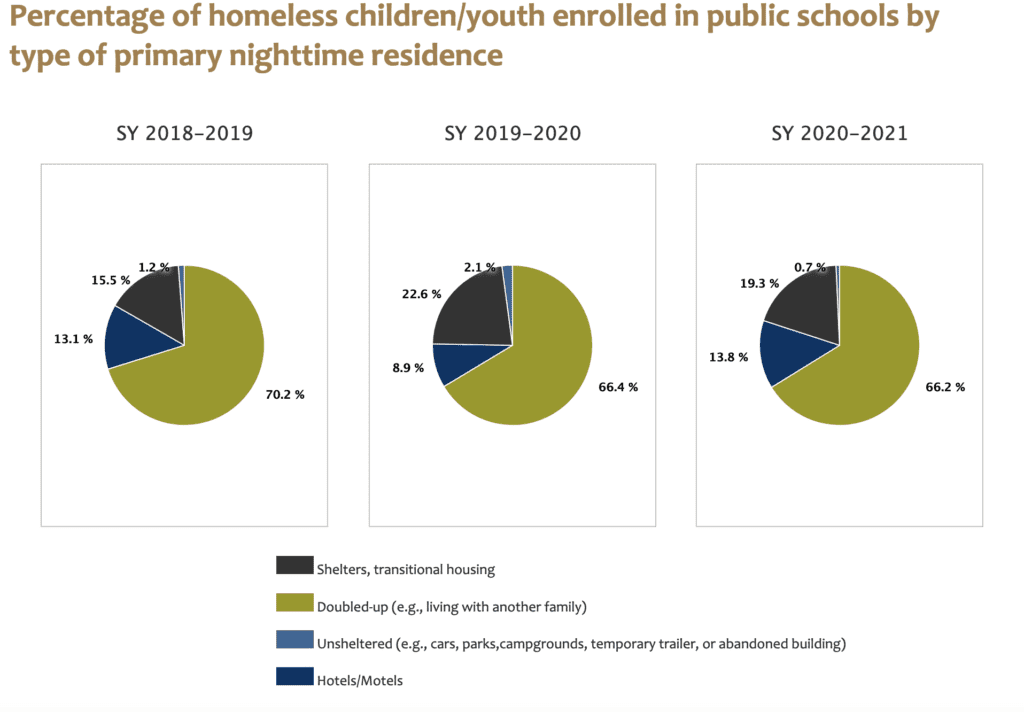

The National Center for Homeless Education provides information on the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act requiring all school districts in the US to ensure access to public education for children and youth experiencing homelessness and to ensure their success in school once enrolled.

The McKinney-Vento Act ensures the educational rights and protections of students who lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence. This includes students who are:

- Living in emergency or transitional shelters;

- Sharing the housing of other people due to loss of housing or economic hardship;

- Living in motels, hotels or camping grounds due to the lack of an alternative adequate accommodation;

- Living in cars, parks, abandoned buildings, bus or train stations, or similar settings.

What is Rhode Island’s Coordinated Entry System (CES)

The CES system, which advocates say needs to stay in place, and the emergency placement of “encampment” people not on the list would bump out others in the queue, waiting. People in the CES system are not just first come first served, they are identified and placed in line by a number of factors. Said about the CES system:

• Coordinated entry is a nationally recognized process developed to ensure that people experiencing a housing crisis are quickly identified, assessed for, referred, and connected to housing and assistance and that everyone has fair and equal access to housing resources.

• In Rhode Island, the Coordinated Entry System is funded by the Consolidated Homeless Fund, the Continuum of Care, and the Emergency Solutions Grants and run by the Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness and Crossroads Rhode Island.

• The Coordinated Entry System serves Rhode Islanders who are currently homeless or who anticipate becoming homeless within the next 14 days.

The RI Homeless Bill of Rights

A major victory of homeless advocates was the passage of the Homeless Bill of Rights in 2012:

No person’s rights, privileges, or access to public services may be denied or abridged solely because he or she is homeless. Such a person shall be granted the same rights and privileges as any other resident of this state. A person experiencing homelessness:

(1) Has the right to use and move freely in public spaces, including, but not limited to, public sidewalks, public parks, public transportation and public buildings, in the same manner as any other person, and without discrimination on the basis of his or her housing status;

(2) Has the right to equal treatment by all state and municipal agencies, without discrimination on the basis of housing status;

(3) Has the right not to face discrimination while seeking or maintaining employment due to his or her lack of permanent mailing address, or his or her mailing address being that of a shelter or social service provider;

(4) Has the right to emergency medical care free from discrimination based on his or her housing status;

(5) Has the right to vote, register to vote, and receive documentation necessary to prove identity for voting without discrimination due to his or her housing status;

(6) Has the right to protection from disclosure of his or her records and information provided to homeless shelters and service providers to state, municipal and private entities without appropriate legal authority; and the right to confidentiality of personal records and information in accordance with all limitations on disclosure established by the Federal Homeless Management Information Systems, the Federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and the Federal Violence Against Women Act; and

(7) Has the right to a reasonable expectation of privacy in his or her personal property to the same extent as personal property in a permanent residence.

Next steps: The court hearing to consider the case of the homeless – on its merits – brought by their attorney that resulted in a temporary restraining order will be considered tomorrow, Wednesday, December 13th. In the meantime, the Governor has requested a specific list of homeless encampments so they can reach out to them. It is unclear if this has been done, though a list by UpRiseRI was posted on Instagram:

Please leave your comments, below – this section is monitored and comments will appear usually within the hour.

UPDATE: The RI ACLU held a press conference Tuesday at 3pm – here is their statement:

ACLU OF RHODE ISLAND AND CENTER FOR JUSTICE SEEK COURT INJUNCTION AGAINST REMOVAL OF CAMPING PROTESTERS FROM STATE HOUSE GROUNDS

Attorneys for the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island and the R.I. Center for Justice have today filed a complaint on behalf of two dozen homeless individuals to allow them to continue camping at the State House to protest the lack of adequate housing for individuals in Rhode Island.

The complaint supplements one filed last week by attorney Rick Corley which led to the issuance of an order temporarily barring any action against the protesters pending a court hearing tomorrow. The supplemental complaint, filed in R.I. Superior Court by ACLU of RI cooperating attorney Lynette Labinger, the Center for Justice’s Jennifer Wood, and Corley, argues that attempts to remove the campers would violate their constitutional rights as well as the state’s Homeless Bill of Rights (HBOR).

The complaint notes that any number of the plaintiffs selected the State House grounds to locate their tent because “they wish to convey a message that they are in need of and unable to access adequate shelter and they believe that the message is best conveyed by their continuing physical presence at the seat of Rhode Island government.” The suit argues that the “grounds of the State House are a traditional public forum where the Government’s ability to limit protected speech and expression is at its most constrained.”

While the notice to vacate given to the camping protesters stated that “camping/sleeping overnight at the State House grounds is prohibited,” the lawsuit points out that the State has not adopted any regulations to that effect in accordance with the R.I. Administrative Procedures Act, a law that requires state agency rules and policies affecting the public to be adopted in a process that allows for public input.

Last December, led by a state Senator and a Gubernatorial candidate, tents were set up on the State House grounds to protest the housing crisis, but all those sleeping there were allowed to stay, and did so for more than two weeks until they voluntarily left. The suit alleges that they were left alone “because they were not homeless or unhoused but acting in their capacities as politicians or housing advocates.”

Although the notice given the campers claimed that “a bed in an emergency shelter” would be provided to every person there, the suit claims that the State has not secured adequate housing for, or even been able to contact, all of them, even as officials seek to have the court eliminate the restraining order and allow them to remove or arrest the plaintiffs. In the meantime, many of the plaintiffs have been trying to work with the state to obtain adequate and appropriate shelter for their needs.

The suit argues that the State’s actions violate the protesters’ First Amendment rights to speech and petition the government, their Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the HBOR, which generally bars discrimination against individuals on the basis of their housing status. The suit seeks a continued injunction to bar the state from “seizing or removing” the plaintiffs without their permission.

A hearing on the injunction request is scheduled to be heard tomorrow at 10 AM before R.I. Superior Court Judge David Cruise. A copy of the complaint filed today can be found here.

RI Center for Justice executive director Jennifer Wood said today: “The urgency of getting the plaintiffs who are staying at the State House appropriate shelter is what motivates this action. The plaintiffs have worked with the state’s lawyers to facilitate getting people who are staying at the State House shelter and it is the goal of the lawsuit to ensure that these individuals and others who are experiencing homelessness in the winter access appropriate shelter.”

ACLU of RI cooperating attorney Lynette Labinger added: “Plaintiffs in this case are individual human beings who find themselves in the most vulnerable situation in the dead of winter. They have chosen to amplify their message of the inadequacy of housing for themselves and other unhoused individuals by presenting it at the seat of government. The law is clear: the government’s ability to interfere with individuals exercising their rights of free speech and to petition the government is at its most limited when that protest is at a public forum like the State House. Instead of taking the time and fulfilling its responsibility to consider, craft and publish narrowly tailored rules limiting the interference with these most basic and fundamental rights and applicable to all, the state has chosen to target this group with arrest and seizure of their property. We urge the State to reconsider its priorities and work with us to find safe and adequate shelter and housing for all of these people and to stop threatening them with expulsion and arrest until they do.”

Attorney Rick Corley added: “The protestors’ mere presence at the State House is intended as a symbolic statement to heighten public awareness concerning the existence of homelessness in Rhode Island. Their physical presence and perseverance to bravely remain vigilant throughout bitterly cold weather emphasize their message that appropriate housing should be a basic civil right.”