Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 19.06.25 (Military Funerals, Job Fair, Benefits, Events) – John A. Cianci June 19, 2025

- East Providence First in U.S. to Equip All Firefighters with PFAS-free Gear June 19, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Saffron Bouillabaisse with Tarhana Lobster Jus June 19, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 19, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Homeless in RI: A system of silos, confusion. The toxic stress of neglect for homeless children

Since December the issue of Rhode Island children who are living outdoors or in unacceptable housing conditions, such as in cars or abandoned property, has posed a question that has no clear answer. Are homeless children neglected children? Do they present a “reportable” incident to agencies charged with protecting their welfare – and future?

In 3 to 4 weeks, individuals and families now housed in temporary shelters will leave those shelters and the shelters will close. The safe haven will be gone. Professional contacts will fragment. Schools and day cares will close and change to summer schedules. Risk for children will raise exponentially.

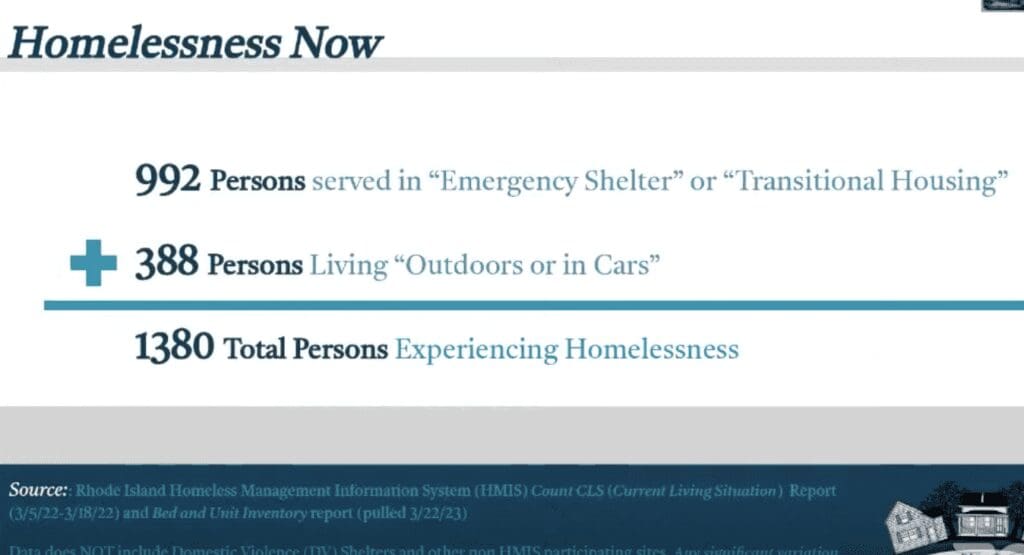

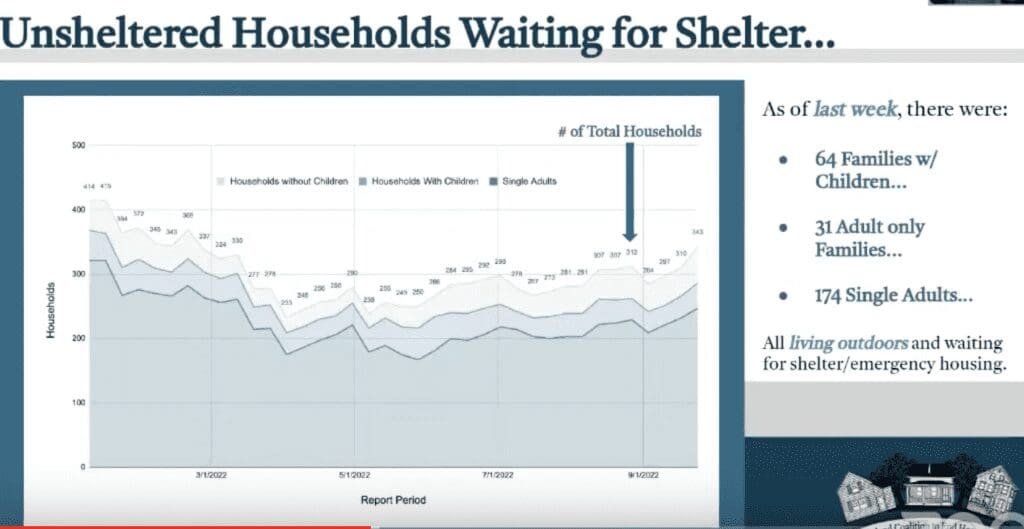

Of the 1,400 estimated people who are living homeless right now in Rhode Island, how many are under the age of 18? Over 600 unhoused people are in the Providence area, alone.

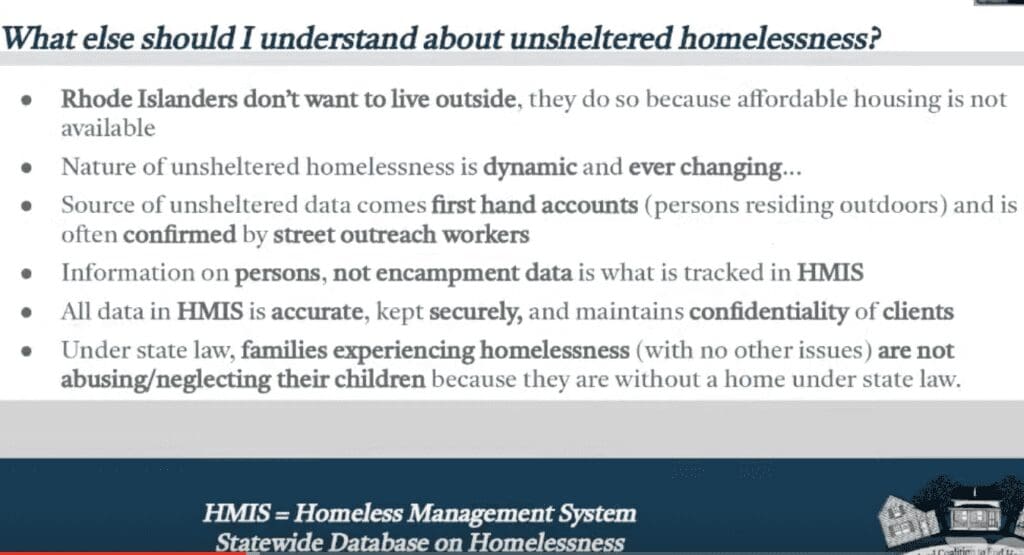

Homeless advocates say that “homelessness in and of itself is not neglect”. They go on to say that if an appropriate living situation is offered to a family with children who are homeless, and they refuse that offer, then that might rise to an issue where the RI Department of Children, Youth and Families would be notified.

According to DCYF, in their annual report, “The majority of child maltreatment nationally, and in Rhode Island, is in the form of neglect. For FFY21, approximately 60% of maltreatment was in the form of neglect.”

Rhode Island is a mandatory reporting state wherein any person witnessing, or having suspicion of, child maltreatment are required to notify DCYF. Reporters can by classified into two sub-populations, individuals who are reporting in their “professional” role, and those who are reporting not in a professional role, “non-professional”, such as family, friends or anyone with knowledge of the circumstances.

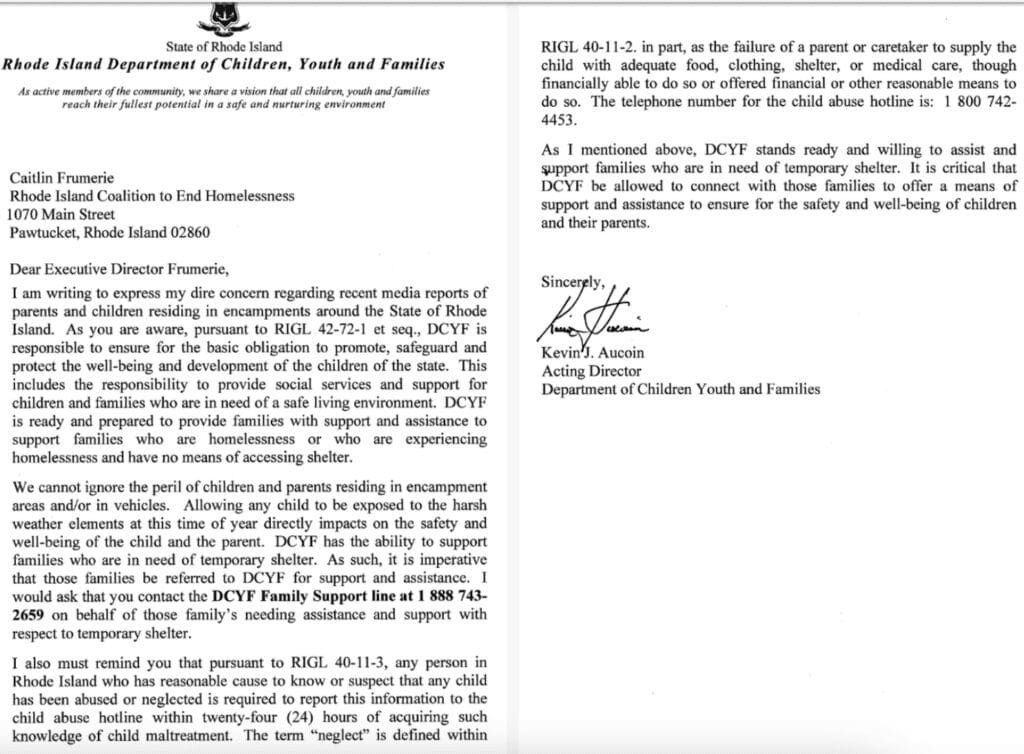

What does DCYF say about children living homeless?

For at least three weeks, RINewsToday asked for a clarification from DCYF about this issue. We received this statement from their communications office, Damaris Teixeira, Public Information Officer, after multiple requests:

“DCYF does not remove children from the care of families who come to our attention for being unhoused, with no other concerns for maltreatment. The Department cannot confirm or deny whether the Coalition [ to End Homelessness] has ever made a report to Child Protective Services. All reports to the Department’s Child Abuse Hotline are classified as “confidential” under State law.

DCYF also provides assistance to support families who are open to DCYF for purposes of achieving safe and timely reunification with parents.

As part of its efforts to provide support to families, DCYF has provided funding support to homeless families for purposes of keeping families together.

At present, DCYF is providing funding to support 32 homeless families who are residing in hotels.

In addition, DCYF provides prevention services to families through a Family Care Community Partnership model. The Department has contracts with five community providers to support this practice model in the state. As part of the agency’s contracts, DCYF provides flex funding to the FCCP providers in the aggregate contracted amount of $230,000 per year. The providers can utilize the flex funds to provide temporary hotel /housing assistance to families. This year the Department has experienced an increase in the number of families in need of temporary housing assistance. As of March 1, 2023, the FCCP providers were providing assistance to support 18 families in hotels.”

The partner agencies of DCYF, called Family Care Community Partnership agencies are:

Family Service of RI – serving Providence & Cranston

Communities for People – serving East Providence, Central Falls, Pawtucket

Child & Family – serving Barrington, Bristol, Jamestown, Little Compton, Middletown, Newport, Portsmouth, Tiverton, Warren

Tri County Community Action Agency – serving Charlestown, Coventry, East Greenwich, Exeter, Hopkinton, Narragansett, New Shoreham, North Kingstown, Richmond, South Kingstown, Warwick, West Greenwich, West Warwick, Westerly

Community Care Alliance – serving Burrillville, Cumberland, Foster, Glocester, Johnston, Lincoln, North Providence, North Smithfield, Scituate, Smithfield, Woonsocket

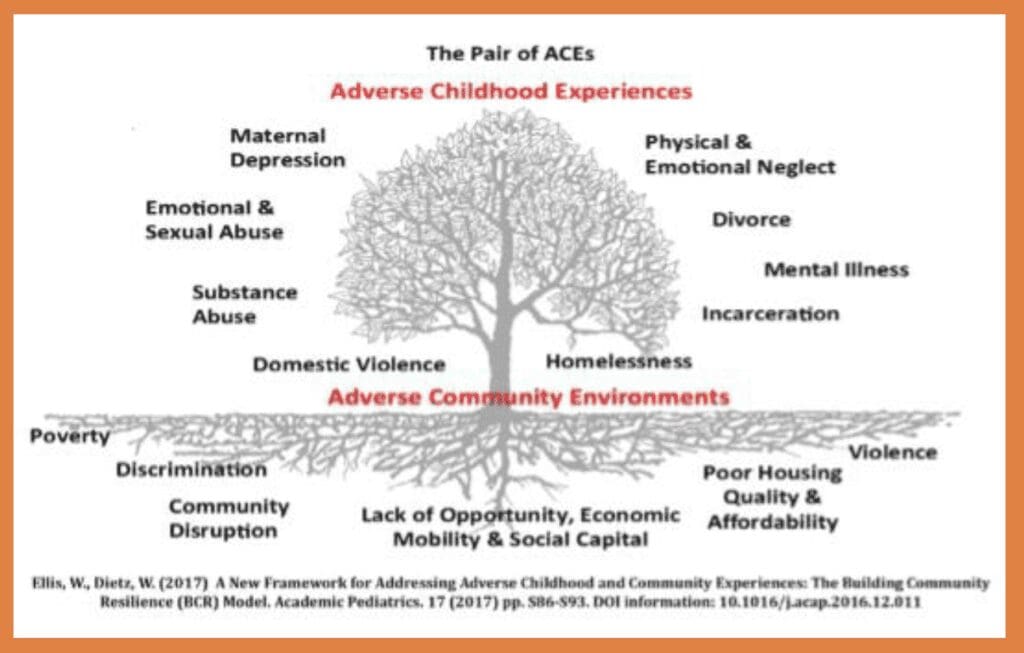

Adverse Childhood Experiences – Toxic Stress

Years ago much attention was given to the issue of “toxic stress” for young children, and lifelong complications – and implications – for the child.

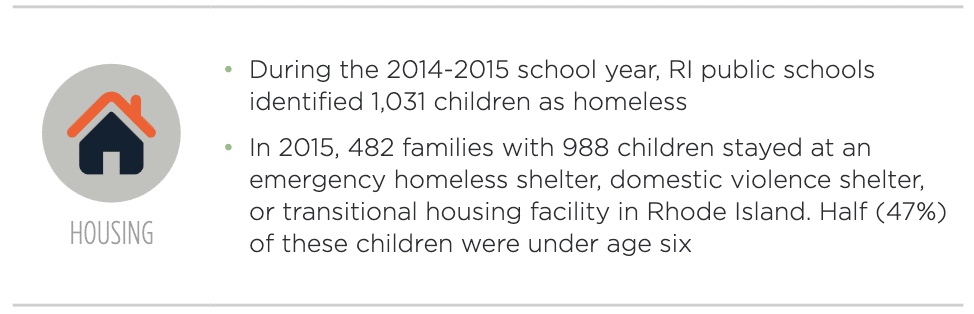

In 2015, RI Kids Count, published an issue brief, “Child Poverty in Rhode Island”. In that report it noted that over 21% of children in Rhode Island were living in poverty – the highest rate in New England. The cities of Providence, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, and Central Falls had the most child poverty.

The report identified the link between poverty, stress, children, and adverse changes in early brain development – “Poverty is linked to chronic stress, which adversely alters early brain development that serves as the basis for learning, behavior and health later in life.” The report noted that “poverty, and the chronic stress it places on children, often results in adolescent and adult difficulties, including physical and behavioral problems, teen pregnancies and unemployment.”

“In terms of solutions, [RI Kids Count] pointed to the issue brief’s position that early interventions are more effective than later interventions, and that targeted interventions can improve children’s outcomes and close gaps between low- and higher-income children…beyond nutrition, childcare and housing assistance, one of the keys is investment in early education.”

Dr. Audrey Tyrka, the director of research at Butler Hospital during this toxic stress report, published a study online in Biological Psychiatry, identifying an association between biological changes on the cellular level and both childhood adversity and psychiatric disorders, including early life stress and anxiety and substance abuse disorders.

More information on Toxic Stress from RI Kids Count:

The report notes the role of the community, and multiple professionals and support systems that should be questioning and asking families about stressors for young children, particularly poverty and housing.

RI DCYF

The agency has a tool to show the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences – known as ACES:

Adverse childhood experiences (the leaves on the tree) can increase a person’s risk for chronic stress and adverse coping mechanisms, and result in lifelong chronic illness such as depression, heart disease, obesity and substance abuse. Physical or sexual violence, and abuse or neglect are often less obvious but can exist as chronic stressors.

Approximately 82 children were involved with RI DCYF in 2020 and 84 in 2021 for ‘unsafe housing’.

Resilience

All reports note the amazing capability for resiliency in children, and provided with early and adequate interventions, how children and families can be assisted and how a path of negative outcomes can be changed – early education is key to resilience, supports of others around them, and presence in school, without sustained absences. It’s also noted that the role of pediatricians, clinics, and other medical systems that interact with families who may be experiencing toxic stressors is essential to a “whole response”.

RI ACLU responds

The RI ACLU was asked for an opinion after hearing the presentation made by the Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness (below). Steven Brown replied, “If DCYF was taking the position that homelessness itself constituted neglect, it is certainly something we would challenge.”

RI Coalition to End Homeless presentation to the Providence City Council:

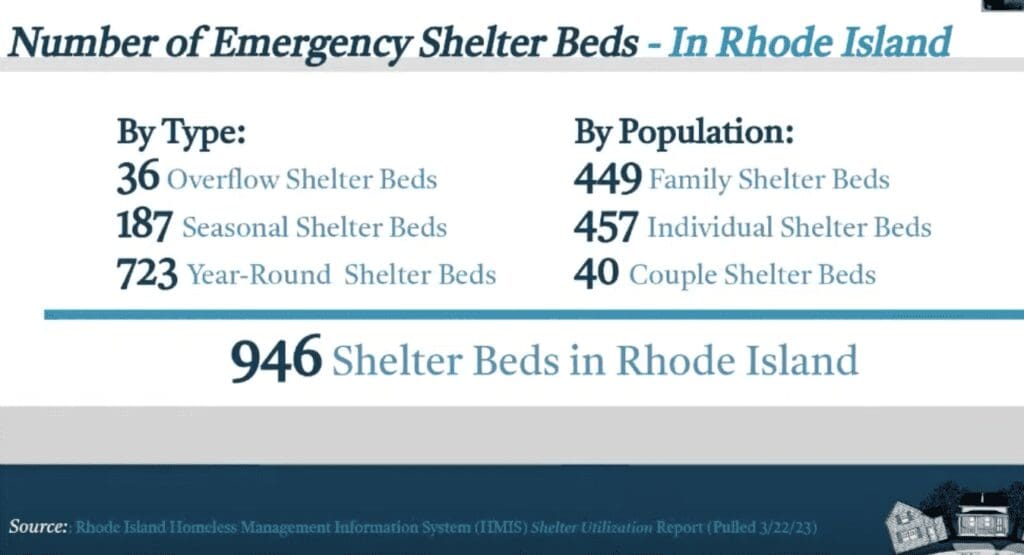

Documentation from this presentation included:

Hiding in plain sight

When the Governor’s office asked for the location of outdoor encampments, they were told that the information, while known to the individual case workers, is not being put into the database out of concern to protect the safety of the families and acknowledging the fear that families have of having their children removed.

Advocates also say that families with children may not be in the count as they are hiding due to their circumstances and fear of losing their children.

Housing and homelessness advocates – who are not child experts or trained in identifying toxic stress in minor children – have made the decision to protect these families. Often, their outreach ends when “stable” housing is secured and interactions are involving the physical needs of the family – housing, clothing, and food. Connections with mental health and substance use interventions are made, but it is not the role of housing advocates to monitor that to protect the families from falling back into homelessness.

A recent family of five came to the RI State House one evening to testify on behalf of families living unhoused – they told their story of losing housing within a month or two of finding it – and going from camping outdoors to a motel room, to couch surfing. No one questioned where the family would sleep that night, or why very young children were at the State House, and not sleeping, nor what the family would do that night for food, or if day care or schooling were part of the children’s lives. The cycle of poverty and homelessness is not an easy one to break.

New family shelter

RINewsToday publicly raised the issue of children living outdoors some months ago. Coincidentally, the state opened a “family shelter” on Hartford Avenue in Providence and several families are now living there. This is not permanent and 3-4 weeks from now – where will they go? What has been the intervention beyond housing, directly to support the children?

Letter from RIDCYF to RI Coalition to End Homelessness

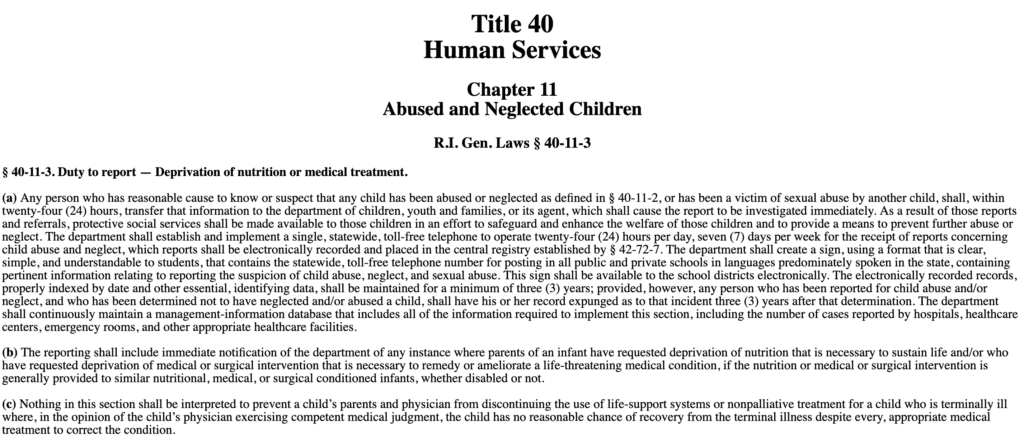

What does the law say?

The law known as “Duty to report” applies to all individuals – regardless of what job they may hold, or what role. The key sentence is: “Any person who has reasonable cause to know or suspect that any child has been abused or neglected…

The definition of “Neglected” is in section 40-11-2:

(1) “Abused and/or neglected child” means a child whose physical or mental health or welfare is harmed, or threatened with harm, when his or her parent or other person responsible for his or her welfare:

(i) Inflicts, or allows to be inflicted, upon the child physical or mental injury, including excessive corporal punishment; or

(ii) Creates, or allows to be created, a substantial risk of physical or mental injury to the child, including excessive corporal punishment; or

(iii) Commits, or allows to be committed, against the child, an act of sexual abuse; or

(iv) Fails to supply the child with adequate food, clothing, shelter, or medical care, though financially able to do so or offered financial or other reasonable means to do so; or

(v) Fails to provide the child with a minimum degree of care or proper supervision or guardianship because of his or her unwillingness or inability to do so by situations or conditions such as, but not limited to: social problems, mental incompetency, or the use of a drug, drugs, or alcohol to the extent that the parent or other person responsible for the child’s welfare loses his or her ability or is unwilling to properly care for the child; or

(vi) Abandons or deserts the child; or…

Failure to Report: RI law says “Any mandatory reporter who knowingly fails to report as required or who knowingly prevents any person acting reasonably from doing so shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and, upon conviction, shall be subject to a fine of not more than $500 or imprisonment for not more than 1 year or both. In addition, any mandatory reporter who knowingly fails to perform any act required by the reporting laws or who knowingly prevents another person from performing a required act shall be civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by that failure.

Are ALL hands on deck to protect the children?

Homeless advocates urge that there be more programs from the substance use system and from the mental health system. But they do not want the help of the child welfare system – whose services clearly go beyond pulling children away from their parents.

With all hands on deck needed to come up with creative solutions, inter-departmental trust and working together is something new Housing Czar, Stefan Pryor, is all about. Hopefully the homeless-family situation is one where the resources of DCYF can be accessed. The medical systems can be accessed. The distrust and personal bias about the state’s child welfare systems might be based in experience, or news reports, but seems misplaced and unprofessional in blocking valuable resources. While homeless advocates know housing issues, they are not experts on child welfare. Will a dialogue begin to bring a village of support to families in need?

Most families will accept shelter if offered, because they are usually homeless out of default (lost job, rental converting to STR for more money, rent going up because taxes and repair costs are increasing to the owner, wages to not keep up with inflation, etc). Families don’t stop loving their children because they are homeless. To remove kids from their homeless parents without cause would result in more stress to the situation. To make a political statement, if our federal tax dollars were spent more on Americans in need instead of buying other countries’ loyalty, we would be a better country (health care, housing, education). The number one cause of household bankruptcy in the USA is medical debt.

Most people think the intervention of DCYF is to remove children – we found a lot of services other than that – most immediate for the homeless, the use of a different pot, or source, of money, if you will, for hotel vouchers and intense intervention to prevent the family from falling into homelessness. Of course if serious mental illness or drug addiction are involved, this also raises the issue of safety for children.

An unacceptable situation. We can somehow justify chronic homeless individual adults who, for whatever reason, choose not to be sheltered/housed, however when there are children at risk, we need to do better.