Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Deconstructing the Hope Street bike lane trial

by Roger Schreffler, special to RINewsToday & Nancy Thomas, publisher, commentary

With the Jorge Elorza administration coming to an end on January 2, many eyes will focus on the new mayor of Providence, Brett Smiley, with surety that he will move forward and stick to his guns to bring sanity to the outgoing mayor’s Great Streets Initiative, a well-meaning but poorly conceived plan to make “every street in Providence safe, clean, healthy, inclusive and vibrant.” Key to Great Streets seems to be using bike lanes – in some cases short bike lanes that go from here to there and aren’t really connected logically to a continuing transportation link. But the use of bike lanes is about much more than biking.

Apart from the word salad of the Great Streets Initiative mission statement, it doesn’t accurately reflect the situation on many Providence streets. Hope Street is a stunning example. It is a heavily traveled thoroughfare, running north to south on the East Side of the city, connecting Pawtucket at its northern end with part of the Brown University campus on its southern end. Unlike Main Street, the busiest north-south thoroughfare, the street is largely residential with several busy blocks of commercial property, primarily small, independently owned businesses, and offices.

Hope Street kerfuffle

Hope Street became the center of a neighborhood controversy last autumn when the local bike lobby (part of a national People4Bikes lobbying group), represented by the Providence Streets Coalition, with the backing of the Mayor and the Planning and Development Department of the city of Providence, tried to take over part of the street to create a protected bike lane. They succeeded in receiving authorization to conduct an eight-day trial in early October based on dubious survey data they produced to justify the request to do so. GrowSmartRI served as their fiduciary agent.

The plan was foolhardy and left questions about why businesses coming out of Covid and always dependent on street parking were being hurt by what some refer to as “woke science”? Bikes, while making people feel good that they’re doing something to save the planet, and a lot of fun for many, are not a serious part of the solution to reducing tailpipe emissions and moving us toward a carbon-neutral world. They don’t show up in the traffic data nationwide, and there is no bike data for the city of Providence.

On Hope Street, more than 6,000 mostly cars travel daily, with outbound traffic slightly higher than the inbound total. During peak hours in the late afternoon, the total reaches more than 500 per hour. That is between 30 and 50 cars each way every 10 minutes.

It is ludicrous to think that bikes can even put a dent in the traffic problem. There are just too many cars, and too many it would appear, to and from I-95 by way of Pawtucket. I-95 is the busiest north-south highway on the East Coast, extending from Maine to Florida.

We don’t know how many bikes are commuting to work, doing daily errands, or substituting for cars, because that would require getting the state involved through the Department of Transportation to collect and analyze data. It is an open secret that there is no love lost between the outgoing mayor, the bike lobby AND Peter Alviti, DOT’s director, who challenged the mayor’s South Water Street bike lane — and lost.

Been there, done that – South Water Street, Eaton Street at Providence College

While one bike lane came and went in short order, another – South Water Street in downtown Providence – was vehemently opposed by local businesses whose delivery vehicles had a hard time maneuvering in narrow lanes, far to narrow for the word “safe” to be used for bikers, truckers, pedestrians and cars, alike. But, in went the protected bike lanes, and not as a trial, but as a “permanent” fixture. Cars learned on their first pass to avoid the area – no one has measured the result on local business. It will be interesting to see if opponents of the South Water Street project seek a second hearing from the new mayor who seems more logical and business-minded; or if others in the city push to investigate failed projects such as the one on Eaton Street in the Providence College community which was installed and then dismantled in a little over a month in fall 2019, after widespread community opposition and costing the city a reported $127,000 and a nasty smudge on the acceptance, or not, of bike lane projects. Some basic things should have been learned. But the Hope Street trial was clear evidence that no lessons were learned, and this time not only residents were upset, but businesses were also disrupted.

Mayor Smiley

During his campaign, the new mayor expressed reservations about the Hope Street part of the Great Streets plan, concerned that there hadn’t been sufficient input from business owners and residents. He spoke clearly about this in campaign interviews on television and in print.

His position seems to have sharpened. The mayor-elect took aim at “bike paths that start out of nowhere and then end abruptly.” And said he wanted to take a total review of the Great Streets Initiative.

In a recent interview with Providence Business News, Mayor-elect Smiley, expressing the views of many residents, said that “There are four or five parallel streets that might be a much more reasonable place — that doesn’t impact businesses — to have a bike lane (in the Hope Street area).

“Real cities have bike lanes,” he declared. “Providence can too. But we’re not going to do them in a way that harms one of the most thriving commercial districts in the city.”

That sounds like a rejection, but business owners and residents of Ward 3, through which Hope Street runs, will be waiting until the new year for the mayor-elect’s formal pronouncement and action. He will be sworn in on January 2.

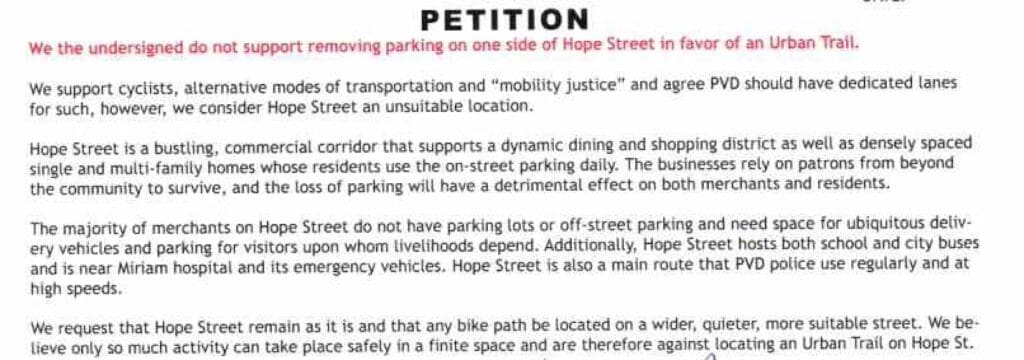

Hope Street merchants and customers speak out – 800 people sign petitions in opposition

Nevertheless, Smiley, who has been consistent in his call for “feedback” from business owners and residents before committing to any infrastructure plan, is expected to receive a petition circulated by the business owners in the coming days or weeks in which they collected more than 800 signatures opposing the Hope Street plan. Included: more than 500 signatures from Providence and neighboring Pawtucket. The community isn’t letting up on making their position known after an experience where it seemed nothing they said or did could stop the Hope Street Bike Lane Trial from plowing through.

It is an impressive number of signatures and action step, considering that the merchants didn’t have the city behind them, thus there were no notices from the Planning Department to promote the petition. It is also impressive because these are mostly customers of the nearly 50 restaurants, novelty shops and assorted other businesses on the street.

Although the Planning Department issued an official survey of their own in mid-October — after the early October trial — and received nearly 1,000 responses, SurveyMonkey, the platform through which the city issued its survey, characterized it as “biased” when contacted by us and shown the question format.

The results still haven’t been announced. We expect the Planning Department to do so after Christmas. Nevertheless, the department asked leading questions — questions that appear to have attempted to elicit a particular response.

By informing prospective respondents that the city’s objective was to make Hope Street “cleaner, healthier, more inclusive and more vibrant,” the department was effectively offering an opinion that the street isn’t already clean, healthy, inclusive and vibrant.

It’s the same sort of mistake the PVD Streets Coalition made in both of its surveys, including the one conducted during the early October trial when volunteers on the street were instructed to tell passers-by that bike lanes are “good for business.”

That is also an opinion, not a fact, and effectively disqualifies the Coalition’s survey by pushing a pro-bike agenda.

The net result: There is no meaningful data.

Other findings based on community feedback.

THE PLAN IS ANTI-BUSINESS.

Business spoke out – but no one listened.

Nearly half of the 50 Hope Street business owners had also signed a letter to the mayor in August, opposing the plan. They complained about lack of transparency and specifically that there had been no public notice until after the decision was made to go ahead with a controversial eight-day street trial between October 1 and October 9.

In fact, outgoing councilwoman Nirva LaFortune did not issue an official notice that Hope Street was being targeted until September 21 for a September 22 scheduled public meeting, nearly a year after the Providence Streets Coalition was brought in to conduct a community survey that constituted mainly postcards in mailboxes of select Ward 3 residents.

“The survey was “super-not scientific,” said state representative Rebecca Kislak. Yet, it was enough to advance the project, get AARP funding, and more, and involve the city’s Planning and Development Department to assist with the October trial.

Candidate Smiley, prior to his primary election, correctly predicted that the trial would be inconclusive and that there would be “a convergence of bike riders onto Hope Street which will,” he said, “raise questions about the data. It is unavoidable. Since I wasn’t part of the original decision process, I am more interested in community feedback.”

The mayor-elect couldn’t have known that the person brought in to administer the trial, working closely with the Planning Department, was a lobbyist for the bike industry. No one could have predicted that the individual would undermine her own legitimacy by organizing a midnight bike-riding event on the final night of the trial, bringing 125 enthusiasts to the street from other areas of the city, or by holding an anti-car documentary film showing on the second-to-last night.

The mayor-elect wouldn’t have known that the individual used the trial to raise money for the Providence Streets Coalition. We don’t know how much in total, but during the trial she tweeted that the Coalition had raised $100,000 for the Hope Street trial project. Undisclosed is that the bike lobby represents on a national level over 300 companies involved in the business end of the bicycle and scooter business – everything from SPIN (electric bike rental company) to 3M (makers of bike lane products including bollards, striping and reflective products) to Walmart.

NOT ENOUGH PARKING

The biggest conundrum for supporters of the Hope Street project is parking. There isn’t enough of it in the roughly two-tenths-of-a-mile stretch through the main part of the shopping district, and there is no realistic way to create more parking. And off-street parking is not adequate to handle the overflow.

There also aren’t enough bike riders for all the disruption in the way the street flows now. Using the bike lobby’s own data, they estimate daily riders at 2.5 per 100 residents. But that doesn’t factor in rainy and snowy days, essentially New England weather, which would bring the actual number down to closer to 1.5%, assuming the industry’s 2.5% estimate is correct.

Which means in practical terms: that a bike lane would have almost no riders for nearly one-third of the year. Thus, those parking spaces would go unused.

It also means that off-street residences in the immediate shopping district area (from the corner of Rochambeau to Lauriston) would be overwhelmed with cars parked in front of their homes, as reportedly happened during the trial.

We couldn’t confirm if any residents were seriously inconvenienced, but we do have pictures of off-street parking extending for hundreds of feet.

Further south on Hope Street, street-facing homes with very little on-property parking had lanes directly in front of their homes with visitors having to park across the street and then navigate a cross-over on one of the busiest – and most dangerous – roads.

Neither the PVD Streets Coalition nor the city’s Planning and Development Department offered a solution to the parking problem.

Not discussed, but the logical next step for the bike lobby is the Hope Street Farmers’ Market.

Had the bike lobby gotten its way, the next logical step would have been to target the small business district at the northern end of Hope Street before entering Pawtucket and including the highly popular Farmers’ Market. The Market, set up on Saturdays for three seasons between Hope Street and the northern end of Blackstone Boulevard, already has serious parking problems, so serious that local home owners both on Hope and the side streets often place chairs or orange cones in front of their driveways. When asked about extending the trail to Pawtucket, thus through the northern end of Hope Street, the Planning Department was evasive.

Postscript: The PVD Streets Coalition, despite asserting that bike lanes are “good for business”, didn’t deliver on its promise. On the four busiest nights of the trial, we counted a total of four bicycles parked outside restaurants at 6:30 pm. On two of those nights, there were no bikes; on one night, one bike; and on the fourth night, three bikes.

With winter now upon us, no bikes can be seen at restaurants as we walk and drive on Hope.

THE PLAN IS ANTI-SENIOR

The trail offered no discernible benefits to seniors who generally walk or use cars to go to restaurants or shop on the street.

Moreover, none of the surveys has addressed the needs of seniors, residents with disabilities who are wheelchair-bound, residents with mild disabilities who are not wheelchair-bound or people with hearing and vision impairment.

And neither the city’s Department of Senior Services, the state’s Office of Healthy Aging (formerly the Rhode Island Division of Elderly Affairs), nor AARP Rhode Island (which funded the trial) could provide any data about the views of seniors who would be affected by eliminating half of parking on the street.

We asked Tim Shea, the community liaison officer at the Planning and Development Department, if we would be getting answers to the following questions:

* How many over-60 residents ride bikes in Ward 3?

* How many wheelchair-assist people live in Ward 3?

* How many wheelchair-assist residents want to use the street (the bike lane) to get to the shopping district?

“You won’t be getting answers,” he said.

Shea also said we wouldn’t be getting answers to:

* How many Ward 3 residents ride bikes daily?

* How many Ward 3 residents bike to work?

* How many Ward 3 residents ride daily in winter, when it rains or on hottest days of summer?

* How many days do Ward 3 residents estimate they ride per year?

But he did say that “Daily riders doesn’t mean ‘daily’.”

Meaning?

THE TRAIL WAS UNSAFE

There are no rules of the road for bike and electric scooter riders, and there were none for the temporary trail installed on Hope Street, a problem that was compounded by having two-way traffic in the lane with one lane running against the flow of traffic. We never observed two bikers passing each other in opposite directions, but there would be simply inches between their shoulders were that to happen, and with bollards standing guard, no room to swerve.

Those problems were exacerbated after dark because the great majority of bikes, unlike cars, are not equipped with proper lighting (head and tail) and most riders (we have no data) don’t wear reflective clothing.

However, reflectiveness in the street markings and bollards did cause quite a few night drivers to note that it literally made it less safe as it boldly assaulted their vision on a road already one that requires all one’s visual acuity.

While we didn’t seek a formal comment from the Providence Police, we did speak to a personal liability lawyer in the neighborhood who almost hit a scooter while trying to turn out onto Hope Street, crossing the bike lane from one of the merchants adjacent to the lane. The scooter was out of his line sight, he said, as one always looks left into the flow of northbound traffic.

His comment: “It’s inevitable that there will be an accident.”

Unstated: also, a lawsuit.

Others criticized the trail for being too narrow and not having adequate protective barriers. But the biggest concern is that there is too much traffic including emergency vehicles, ambulances in particular, which use Hope Street to get to one of the local hospitals. When a biker said emergency vehicles will be able to “go around” as cars would no longer be able to pull to the furthest part of the roadside, one firefighter responded, “we’ll drive right over those white bollards” if we have to.

THE TRAIL FOCUSED ON THE WRONG PROBLEM.

THE RIGHT PROBLEM? SIDEWALK SAFETY AND PEDESTRIAN CROSSINGS.

The Planning Department’s survey did not ask respondents to prioritize their most pressing infrastructure needs. Almost as an afterthought, the department asked, “What other improvements would you like to see?”

Reviewing comments on an online neighborhood forum, the only thing almost everyone seemed to agree on is that sidewalks need repair and pedestrian crossings need to be upgraded. There was no consensus on the bike trail and, as we reported earlier, more people opposed the trail than supported it.

The need to repair sidewalks that are cracked and lifted and dangerous was noted by merchant and customers alike.

ELORZA’S “GREAT STREETS” LEGACY?

Mixed.

The outgoing mayor clearly didn’t use good judgment to try to place bike lanes throughout the city. Conceptually it’s nice to talk about things like “mobility justice” and making the city’s streets “accessible” to all, but some streets just aren’t suited for bike lanes. Hope and Eaton are two examples. Placement and safety – for all – is critical.

Perhaps the Broad Street project will be its most successful, though a radio celebrity noted that while he bikes all the time, he would avoid the dangerous mess that Broad Street has now become. He noted the number of electric scooters and boards in use, going much faster than a cautious bike rider would.

As one critic said, “Providence is not Amsterdam,” referring to the mayor’s reported affinity from day one in office with biking. After becoming a dad, and now having a 3-year-old who he acknowledged wouldn’t be going to Providence Public Schools, we wonder if he would feel safe for his son to join bikers on the back of his own bike, or one day on his very own, on Hope Street?

He also didn’t listen to the stakeholders, in particular the business community. Witness the South Water Street dispute, then the dispute with Hope Street merchants. Not to mention the Providence College community.

As more than 20 Hope Street merchants wrote to him: “The idea may make for an attractive rendering in a presentation but, in reality, Hope Street is a narrow, commercial corridor that needs to attract customers from far and wide to survive.”

SUGGESTIONS

Time for a sidewalk review – talk to the store owner who has had at least five people fall on a sidewalk outside his store on Hope Street because of cracks, or the person who stepped out to where a crosswalk was, but it had been painted over after a street repair was made and was nearly hit by a passing car. Back to basics is what many city residents want in their administration – garbage pickup, safe roads and walkways, street sweeping, plowing, etc. Until all that is “reimagined” moving to bike lanes is definitely down the line in priorities.

Look for some wide swath of street where bikers and drivers can co-exist. Safely. Give up on this plan to “calm traffic” by retrofitting skinny bike lanes. Assume that very few will actually use them. Use logic. Take into account what homeowners and business owners have to say. And don’t use questionable data. If we need numbers, then we have to pay a professional who doesn’t have a vested interest in the outcome. Bikers should also know the rules of the road, and many states have gone to licensing, exam taking, and fines for not wearing helmets, reflective accessories at night, and ticketing for road infractions. Even mandatory insurance is beginning to take hold.

STEP NUMBER ONE

Advice to the Mayor, as we’re sure he’s getting a lot – go visit the Hope Street merchants. Store to store. The city needs to make amends, even if it’s just a verbal gesture and friendly visit. Allowing disgruntled store owners – as well as those who were in favor of the bike lane, to talk and be listened to would be helpful. The last thing needed is more polarization and disagreements – over something that should be enjoyable and positive: safe bike-riding. Driving in our community. Parking close to where we shop. Having our children safely play and walk where they live. Saying that one is sick of listening to “older, whiter, wealthier” and the “crazy old lady” in the room, on Twitter when opposition of home and business owners is raised, well, need we go on?

___

Other stories done on the Bike Lanes of Providence: https://rinewstoday.com/?s=bike

___

Thank you to Roger Schreffler, our collaborator on this series of stories. Schreffler is a veteran correspondent and business writer who has spent more than 30 years covering the auto industry and technology involving the industry including electric cars, fuel cell cars, batteries, and smart mobility. In addition to his regular reporting for Ward’s Automotive, he’s written half a dozen research reports on advanced powertrain technology including EVs. For the past 18 months, he’s been covering the Carlos Ghosn story for Asia Times.

He and his wife have lived on the East Side for 20 years, moving to Providence from Tokyo. He credits the Hope Street business owners with helping us all get through Covid and feels that both the city and the PVD Streets Coalition have treated them shabbily.

While he has nothing against bike trails, he fervently believes that neither bikes, nor electric cars, in cities like Providence are the answer to reducing tailpipe emissions, at least not for another 5-10 years. For the time being, he says they’re “feel good” technologies. His preference: some sort of mass transit, probably electric minibuses, trying to replicate the Brown and Lifespan model.