Search Posts

Recent Posts

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 12.06.25 (Memorial Day, Vets Cemetery, Events, Resources) – John A. Cianci June 12, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Mediterranean Seared Salmon, Olive Tapenade, Artichoke Hearts, Roasted Red Pepper Tahini June 12, 2025

- Why more Rhode Islanders are choosing Heat Pumps over traditional AC this summer June 12, 2025

- CNAs to be trained at URI in administering medication in state facilities June 12, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 12, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 12, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Cranston Police Academy shooting range so much noise for residents. Brown U. study. (updated)

Updates in red:

Photo: RI Police Chiefs Association

Residents of Cranston who live closest to the Cranston Police Academy have been “on fire” about the increasing sound of gunfire coming from their shooting range. They say it is much more than annoying, and is impacting their quality of life, health, sense of well-being, and quite possibly standing in the way of their being able to sell their homes.

After at least 2 years of intensive work to find a solution, with presentations to the Cranston City Council and appeals to the Mayor’s office, possible solutions have not yet been realized.

There was the idea of sound-proofing the building, as other gun training ranges are, most notably in Coventry and at the State Police facility. Sen. Jack Reed had indicated federal funds might be available to help with that, and the Mayor’s office proposed a multi-year funding, with a plan that would take 2 to 3 years to fully implement. It appears as though funding, as well as a legislative bill prohibiting shooting ranges near schools, which would have meant the range would have to close, have not been realized.

There was the idea to move the facility – but who would want a firing range in their backyard? Moving it might prove very difficult if not impossible. With income coming into the city from outside police departments, and even college training groups such as URI, there could also be a budgetary hit to the city.

Residents don’t have too many constructive solutions, other than they want the problem addressed. To their credit for tenacity, the group engaged Brown University’s Community Noise Lab, out of the School of Public Health for a noise study.

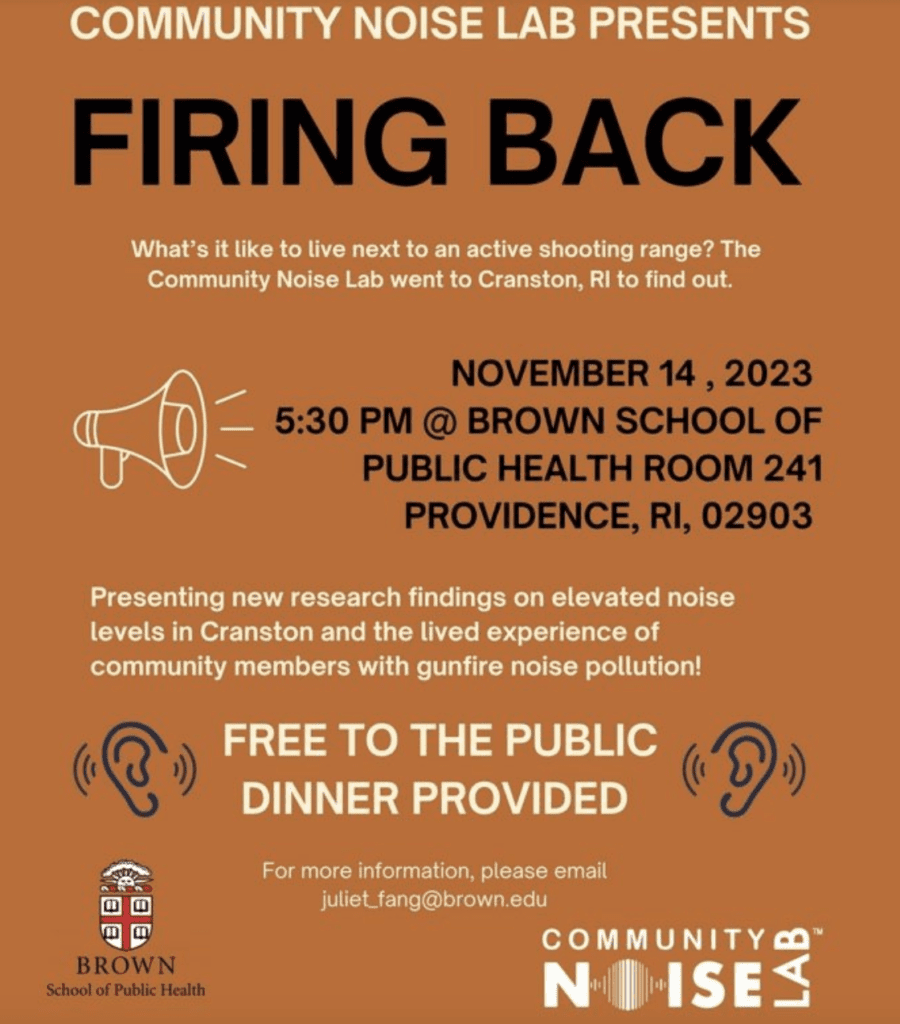

On November 14th, there will be an event – FIRING BACK – where the study (see below) will be presented in greater detail.

___

Why noise?

Atmospheric air pollution and water pollution are far from the only environmental harms that affect the health and well-being of humans. Noise pollution, or the propagation of unwanted or disturbing sounds, poses a significant risk to the physical and emotional health of children, adults, and seniors. Cities are especially susceptible to noise pollution as the urban environment exposes individuals to constant noises of traffic congestion, construction, and airplanes.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between excessive noise and health, demonstrating a link between noise pollution and sleep disturbances, heightened blood pressure, increased stress, cognitive impairment, and anxiety. Experimental studies suggest that, by increasing stress hormone levels, excessive noise triggers the body’s stress pathways and can contribute to the development of chronic diseases such as stroke, hypertension, and heart disease in the long run. Additionally, noise pollution tends to intersect with other forms of environmental health concerns (i.e. air pollution, water pollution), exacerbating and creating new health conditions, especially for minorities and mid to low-income individuals. A study by researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the University of California, Berkeley, observed consistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in cities exhibiting racial segregation compared with more integrated cities, highlighting the relationship between environmental injustice and social determinants of health.

How Community Noise Lab Measures Sound and Noise

· A-weighting: Measures the sound pressure level in a given area. The A-weighting system prioritizes the sounds we process through the auditory system. Therefore, this system applies an adjustment to sound measurement that emphasizes the frequency range 2000-5000 Hz.

· C-weighting: The C-weighting system applies an adjustment to sound measurement that emphasizes low frequency range 30 to 10,000 Hz. This weighting scale is good for measuring impulse sounds, including explosions (like fireworks) and gunfire.

· Frequency: the number of times per second that a sound wave repeats itself, creating a high or low pitch.

· The Octave Band: a filtering method of splitting sound into smaller segments called octaves, allowing researchers to group noises with similar physical properties together.

· Low-frequency Sound: sound with a frequency towards the lower limit of audibility (i.e. motors)

· High-Frequency Sound: sound with a frequency that towards the upper limit of audibility (i.e. whistles, screams)

· Noise Perception: how an individual (or community) feels about certain sounds.

· Short-term and long-term exposure: the length of time an individual is exposed to noise

· Peak Sound Levels: is the maximum value reached by the sound pressure during a specific time period.

Cranston, Rhode Island

In Cranston, a city in Providence County, Rhode Island, noise pollution doesn’t come from cars or factories — it comes from gunfire noise. There, the Cranston Police Academy operates an outdoor shooting range for Cranston Police Departments and the Rhode Island Police Municipal Academy. The range is used year-round by Cranston’s 160+ officers as well as hundreds of officers from nearby cities and private organizations.

First established 1956 as a shed in an empty field, the shooting range has since grown to become a full-fledged training facility surrounded by residential neighborhoods and located directly across from Cranston High School West and Western Hills Middle School, and just over a mile from George Peters and Stone Hill Elementary. Additionally, there are nursery schools, daycare centers, group homes, nursing homes, and houses for seniors and the disabled located within a mile and a half from the range.

Cranston Police Academy (grey, gun symbol) surrounded by schools, a senior retirement center, and residential areas (colored by density). Click and pan on the map to explore.

Per state law, all Rhode Island police officers must complete certification each year on three weapons, resulting in firing of hundreds of rounds. The Cranston force alone — excluding training and practice time — shoots 48,000 bullets for the qualifying tests.

Additionally, the Rhode Island Municipality Police Academy utilizes the Cranston range to train and test 60 to 120 cadets every spring and fall, sending the noise of gunshots throughout the surrounding area.

According to a Providence Journal follow-up story on Nov. 14th, “Only two or three departments outside Cranston use the facility for handgun qualifications, the feds are gone, and for the first time this year, the Municipal Police Academy is no longer training there. Instead, it will train at the State Police Academy range in Foster.”

Built in an old quarry, the shooting range deflects the noise from Glock pistols and off a rock ledge adjacent to the range, causing gunshots to echo throughout the surrounding neighborhoods. According to residents and students, the gunfire noise can be heard from inside the schools, distracting students and impairing their learning and hearing capabilities. Students have reported that teachers must raise their voices to be heard over the gunfire, and a special-education assistant at Western Hills said many of her students have a very difficult time learning when there is shooting. An additional concern of Cranston residents is that students could be desensitized to actual gun violence if they are constantly exposed to gun noise.

“It is unconscionable that a gun range—where military-grade weapons are fired—is so close to schools. No child should have to listen to war-like gunfire outside the classroom door. No community should be subjected to this kind of abuse.” says Martha DiMeo, a Cranston resident.

“The reality is, if there is a shooting at the schools or in my neighborhood, no one would notice and call the police.”

Methods

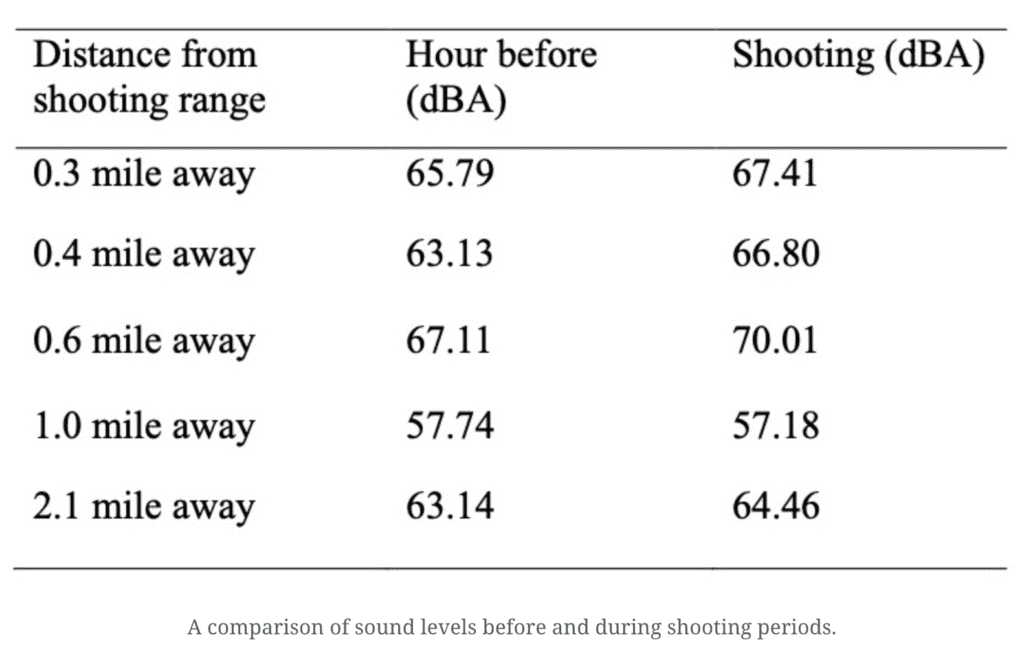

Data were collected at six residential sites using noise monitors in November 2022 and April 2023 for a one-week period. Sound levels were captured in one-second increments and averaged to a variety of temporal resolutions including minute, hour, day, and week. Sites were located at variable distances away from the gun range, ranging from 0.3 to 2.1 miles away from the range. Data were then compiled and analyzed across the time period.

Results

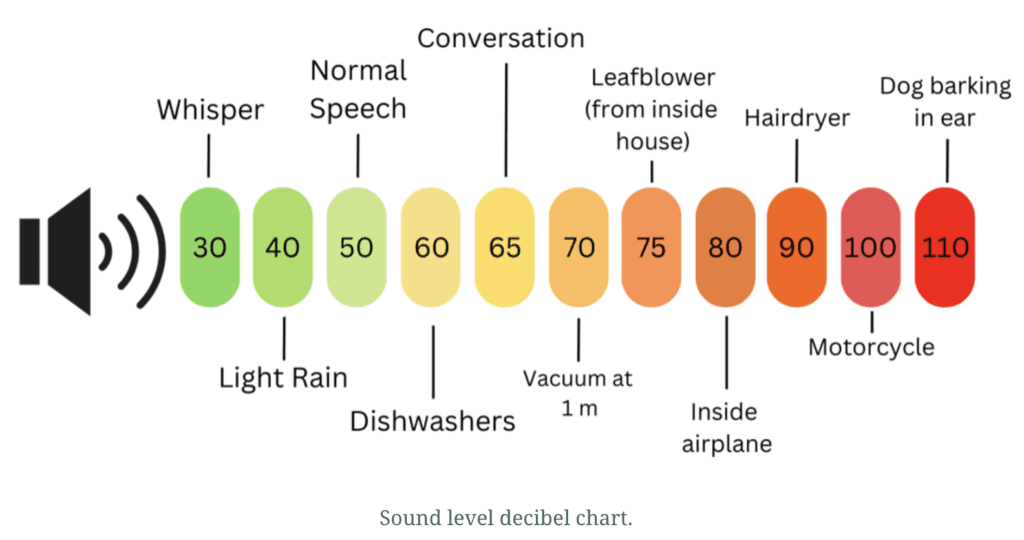

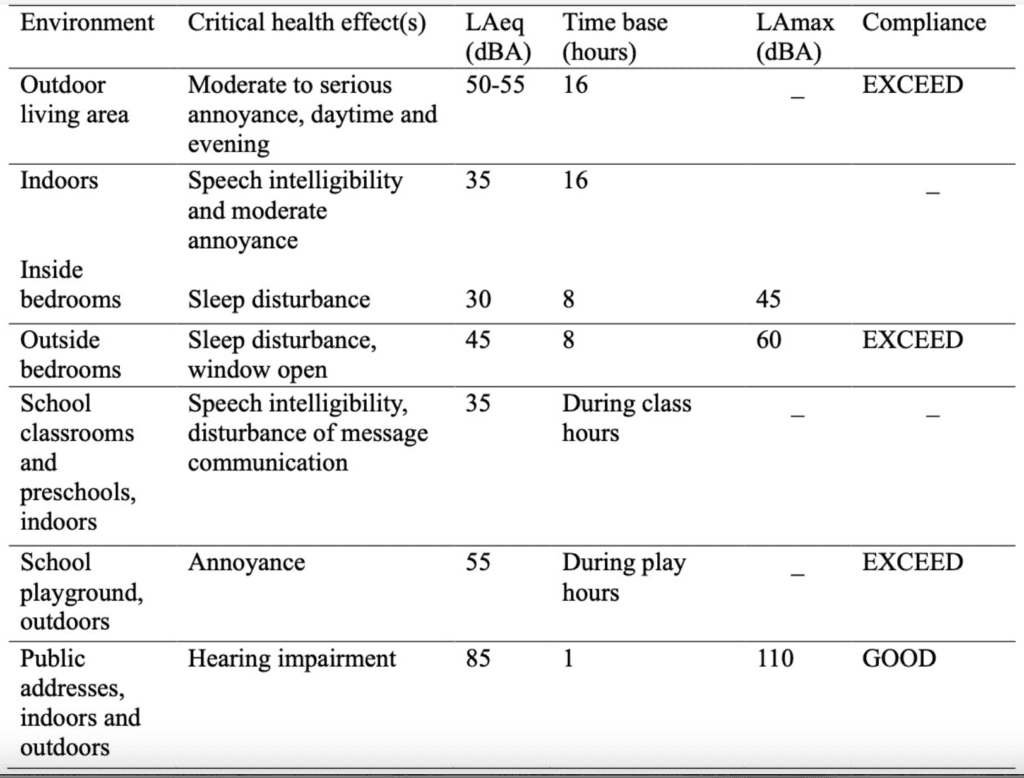

According to data collected from residential neighborhoods by the Community Noise Lab in November 2022 and April 2023, gunfire noise in Cranston can reach 82 decibels (dBA) during shooting periods, approximately the loudness of the interior of an airplane. This peak noise level is approximately 1,000 times louder than Cranston’s noise ordinance for residential neighborhoods (55 dBA).

At the five sites where data were collected, the peak sound level during periods of shooting was statistically significantly higher during times of shooting than the peak sound level the hour before shooting across November and April data collection periods. Stratified, each site, with the exception of one, which showed a slight decrease, reported peak sound levels during minutes of shooting that were well above the Cranston noise ordinance, refuting Cranston Chief of Police Michael Winquist’s claim that noise from the range is within city laws. Chief Winquist has also stated that natural vegetation such as bushes and strips of wood mitigate the noise from the shooting range, but sound levels persist at a harmful range.

As seen above, the difference in peak sound level tended to decrease the further away from the range for most sites, with the site 0.4 miles away from the range reporting the greatest difference in noise level between the hour before shooting and during shooting. The average noise level across all sites and data collection periods was 47.6 dBA, while the average peak noise level was 72.1 dBA.

Each site also reported much higher levels of low frequency and C-weighted sound than high frequency sound, indicating that much of the noise in the Cranston area comes from lower, rumbly sounds, such as road vehicles, aircrafts, and artillery explosions.

Overall, the average C-weighted sound level, low frequency sound level, and high frequency sound level were 60.55 dBA, 62.32 dBA, and 40.56 dBA, respectively.

The site 2.1 miles away from the shooting range reported the greatest intensity of C-weighted and low frequency noise (although not by much), while the site 1.0 mile away from the shooting range reported the lowest values for the same measures. This site also reported the greatest intensity of high frequency noise, such as sirens and birds chirping.

Although our data collection and analysis methods follow standard protocol for noise research, our results should be interpreted within the bounds of the possibility of human error.

Health impacts

According to the CDC, prolonged exposure to noise above 70 dBA can cause hearing damage, meaning that, during times of peak shooting, the gunfire noise is loud enough to cause hearing damage to Cranston residents, especially those closer to the range.

The CDC additionally notes that the typical response after routine or repeated exposure to noises in the 70-85 dBA range is mild to great annoyance, emotions Cranston residents frequently experience.

How can an emotional response lead to acute and chronic health impacts?

Once noise disrupts the mood, it sets off a “fight or flight” response. In the short run, your body experiences increased heart rate, sweating, stress, and rushes of adrenaline. In the long-run, this extended bodily response could lead to the manifestation of a variety of negative health outcomes, such as hypertension and heart disease.

How loud should noise be?

The World Health Organization (WHO) establishes strict guidelines for sound, summarized in the table below. The rightmost column indicates whether or not noise levels in Cranston, according to our study results, are compliant with WHO sound guidelines.

“Gunfire is not white noise”

Two people leading the charge against the gunfire noise in Cranston are long-time residents Martha DiMeo and Pat Schoeninger. Both live less than a half a mile away from the shooting range. They have organized many members of the community against the shooting academy practices and testified numerous times before Cranston City Council, urging for action to be taken to mitigate the gunfire noise.

“The noise level started to intensify about 6 years ago,” says Martha DiMeo. “Instead of sounding like popcorn off in the distance—as it had for decades—one spring afternoon there was sustained gunfire with multiple shooters. I called my Ward 5 Councilman, Chris Paplauskas. He informed me that the police were now training on AR-15s and other high-capacity weapons. He also shared that Cranston had decided to monetize the range by renting it out to other cities and private organizations.”

Cranston, April 2022. Video: Sherry Izzie

Schoeninger observed a similar trend in increasing gunfire noise. “When I first moved to Cranston in 1978, the gunfire noise was very sporadic,” she says. “I could deal with it at the time. The police department got bigger as time went on. There were more guns, and they were bigger and louder. Then, the academy starts renting out the shooting range and the sound becomes unbearable.”

“We were never told when the department started renting out the range. I felt invisible. [The department] told us that what they were doing was called good gunfire. It’s ridiculous. There’s no such thing as good and bad gunfire, and how are we supposed to know the difference in an emergency?”

For residents of Cranston that who, like DiMeo and Schoeninger, work from home or are retired, living at home during times of gunfire is an almost unbearable option.

“The medical facts are not up for dispute. Being barraged with gunfire 8-12/hours a day is inflicting physical and mental harm,” DiMeo says. “Once the shooting starts, my day is over; I can’t function. I feel my stress level, anxiety, and blood pressure rise. I can’t concentrate; I can’t work.”

Dr. Patricia Ricci testifying before Cranston City Council

“I tried different things to dampen the shooting noise,” says Schoeninger. “Closed doors, closed windows. Making the television louder. Making the radio louder. It wasn’t working. I had to leave my house and drive [five] miles to Roger Williams Park and sit at the Temple of Music to escape the noise.”

“Leaf blowers and gardening equipment are annoying noises,” she continues. “But gunfire signals our bodies to go into fight or flight mode. So the only way I could escape the noise was to leave my home to go somewhere else so I don’t have to hear gunfire.”

For children living in Meshanticut, Cranston, gunfire noise has become a part of everyday life, especially for those attending Cranston West, the high school directly across the street from the shooting range.

Cranston West football practice, November 2021. Video: Pat Schoeninger

“When kids visit Cranston West to compete in track and field, they drop [to the ground] when they hear the gunfire,” says Schoeninger. “And you know what Cranston West students do? They laugh. Because the kids dropping on the ground, to them, are being abnormal. Cranston kids have become desensitized. They hear gunfire during class, during lunch, and active shooter drills, even.”

“During an actual emergency involving gunfire, we wouldn’t know to call 911 because we’re so used to it. The police might’ve not even known, and just told us that the noise was coming from the range. That’s terrifying.”

Community action

Concerned about the health and safety of their community, DiMeo and Schoeninger teamed up during the COVID-19 pandemic to organize Cranston and demand action to reduce the shooting noise in Cranston that was, at the time, occurring seven days a week. When the mayor refused their request to hold a town hall meeting to discuss the noise, the two created a petition and knocked on doors, receiving over a hundred signatures.

“When we knocked on neighbors’ doors, they said ‘Where do I sign?’ right away,” says DiMeo. “They were thrilled we were taking this on. Many neighbors told us they had contacted City Hall and were dismissed and ignored. They were told — as I had been told — that they were the only one complaining. They felt powerless and hopeless that anything would change.”

Despite the petition’s initial success, several years later, the invitation to the mayor to hold a town hall meeting is still pending.

DiMeo and Schoeninger have also spoken to various state officials about the issue, as well as testified before Cranston City Council numerous times. Even with all these efforts, the two feel they have not been heard by those who are supposed to represent them.

Currently, DiMeo, Schoeninger, State Representative Brandon Potter, and other residents of Cranston are working to pass Bill H-5367, which would prohibit outdoor shooting ranges within a mile circumference of schools. Since the Cranston police shooting range is within a mile circumference of approximately four schools, it would have to either be enclosed or shut down. Currently, the bill is being held for “future consideration and review.”

Additionally, a 1.6 million dollar grant to enclose the facility was submitted in April 2022. While waiting for the grant decision, no site surveys, site plans, or cost estimates were initiated. The grant was denied in December 2022. No further plans to seek funding have been shared with the public.

DiMeo is frustrated by the lack of care city officials have given its residents. “Nothing is getting the attention of this administration or the City Council,” she says. “Not doctors testifying to the medical implications—heart disease, high blood pressure, increase cortisol levels—or their constituents pleading with them to do something.”

On October 24, 2022, Dr. Patricia Ricci, a Rhode Island psychiatrist — board certified in psychiatry and neurology — testified before the Cranston City Council about the physical and mental harm inflicted on the residents of Cranston from the daily barrage of gunfire. She implored the Council to act immediately. The then-Council President Chris Paplauskas had no comment other than to compliment Dr. Ricci on her timekeeping abilities. The Council failed to act on her urges.

Dr. Patricia Ricci testifying before Cranston City Council

Schoeninger shared similar feelings of being ignored by her community representatives. “I’m not invisible,” she says. “I’m here. I’m telling [City Council] that this is harming me, and they’re not listening. Instead, I’m being told to get used to it. What happened to having character, or decency?”

“This does not happen in wealthy communities. East Greenwich, one of the wealthiest towns in Rhode Island, had an outdoor shooting range. When the developers and neighbors complained, the training was moved to a military base,” adds DiMeo.

DiMeo and Schoeninger want the gunfire to stop. The inaccurate shooting schedule, they add, is inherently asinine and discriminatory.

“No one should be told to leave their homes,” says DiMeo. “It’s gross negligence on the part of city officials who are elected to protect us.”

“We have the right to the peaceful enjoyment of our homes. Their inaction is denying us that basic right.”

___

About the Community Noise Lab

Community Noise Lab is currently located at the Brown University School of Public Health. Overall, our lab’s primary aim is to holistically explore the relationship between community noise and health by working directly with communities to support their specific noise issues using real-time monitoring and exposure modeling; our smartphone app, NoiseScore, which allows users to objectively measure and subjectively describe noise events in their community; community noise surveying via our National Neighborhood Environmental Noise Survey; laboratory-based experiments, and community engagement activities.

This is a developing story – the city of Cranston has been asked to respond to the study’s findings – at press time we had not received the information – check back for added info.

___

Past stories done on the police shooting range issue:

A simple solutionwould be to make sound suppressors legal for all law abiding Rhode Island citizens.