Search Posts

Recent Posts

- GriefSpeak: Waiting for Dad – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 13, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 13, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 13, 2025

- Urgent call by Rhode Island Blood Center for Type O- and B- blood June 13, 2025

- Real Estate in RI: Ready, Set, Own. Pathway to Homeownership workshop June 13, 2025

- Outdoors in RI – Risky cattails, Fight the Bite mosquito report, 2A gun ban bill update June 13, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

“Cancer” – a short story by Michael Fine

by Michael Fine

© Michael Fine 2020

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

It made no sense. There was only one person on Elliot’s mind that night despite all the people who had gathered. All Elliot could think of was Leslie and whether she would be there or not.

The whole band was there, the new guys and all the old guys. They’d come from all over the country and from all around the world. Phil came in from LA. Steve from Austin, Jack from Bali where he lived on the beach, drinking and hanging out, making tourist money from street music and gigs in bars. It was good to see those guys, and it filled Elliot’s heart in an unexpected way, like maybe his life was actually bigger than he thought it was, as if there was this huge part of himself that he didn’t know was there. They came, they played, and they were tight, note perfect, timing perfect, better than they had ever been. You wouldn’t think the old guys and the new guys would mesh so well, know the music, know the timing, and give each other space, but there it was. One practice session and they had it down, the old stuff and the new stuff. Perfect. The old guys were respectful of the new guys and followed their lead; the new guys conscious of the old guys and their skills, so everyone played their piece. Even Jack behaved. Solid, hot, bluesy and soulful. Jack managed to keep a lid on his virtuoso lead guitarist shit, the stuff that blew everyone out of the water but didn’t give bandmates a moment to breathe. So, the music was right, and they were musicians together, playing for one another and for something else, something that made them way more than the sum of their parts.

And man, people came. They sold out The Urban three nights in a row. People Elliot hadn’t seen in fifteen or twenty years along with his little clan of groupies, the people who showed up almost everywhere the band played. Schoolteachers. Nurses. Lawyers. Bureaucrats, truck drivers and mechanics, the women in slinky pickup tops and the men busting their asses to look like they didn’t give a shit, in jeans and tee shirts with baseball hats and watch caps. Some of the guys had gained a bunch of weight and looked pretty lame, dressed like that even though they wore suits and ties for the day job. Some of the women had also crossed over into a different life, their skin thick and blotchy, their clothing matronly, their graying hair short so they didn’t have to bother with it anymore.It didn’t matter. These were all Elliot’s people. They had lived together and loved and cheated and were cheated on and played and danced and sang and died and lost friends and lovers and families along the way. They came, and they danced, and they all pretended together that nothing had or would ever change.

The Urban, in Pawtucket, their home venue in the old mill, was perfect. The staff asked no questions when they heard Elliot was sick. They just organized a benefit. Day and time. Other bands to come. Up on social media, so everybody in Providence, Worcester, Fall River and New Bedford knew. Hell, even the Boston people knew.

Elliot himself was on. His voice and his timing were all there. He led like he always did, and everyone fell in behind him. Not an ego thing. Just the way it was. Pain under good control. It was there but he could ignore it. It was a fist just under his chest that had his innards in its grip and twisted them from time to time, like the fist was going to rip those innards out and drag his heart out with them. But his mind was on other things. He was in another place. The pain was there, but Eliot could put it in a box, in another room, so he could play and sing as if nothing else mattered.

The fist was how it started, the thing that Elliot would eventually come to call the cancer. The thing, the fist, the catch, the rock where there had never been a rock, started as a question – what’s that, is there something there? And then it became a statement, then a paragraph and then it took over his brain and his life so that it was all he knew and all he felt. He dropped twenty pounds in a couple of weeks, so quickly he didn’t notice it, but everyone else did. They said he looked gaunt. Elliot was always a thin guy, thin and wiry, which is how you roll when you play guitar and spend half your life on stage, fronting this band and that. So, no one ever said, hey Elliot, you lost a little weight, looks good on you. No, all they said was nothing except, hey man, you okay? But Elliot saw the questions and the fear in all their eyes, and finally admitted to himself that this was a thing.

Getting diagnosed and treated was tricky though. Elliot was a musician, by god. He lived all his life in second and third story walkups off Broadway and in Pawtucket or Cranston. Even lived for a little while in Central Falls. Once, he lived in a converted chicken coop in Foster. Musicians don’t do health insurance. You live for the band, for the song, for the gig and for the contract. You hope for a girlfriend who has benefits. Some guys teach school or work as carpenters or even roofers by day. But that wasn’t Elliot. In high school he played a little and thought he’d end up an accountant or lawyer and live in a white house with the picket fence in Barrington or someplace that specialized in white houses with picket fences. But then the music began to move, the bands jelled, fell apart and jelled again. The Elliot wrote a couple of anthems that got everyone on their feet and everyone dancing, and then he couldn’t put it down. Locally famous. Toured in California, Texas, Georgia and New York. Clubs, not concerts, but always just on the cusp. And the music. The music was better than fucking, in its own way. Fucking came with wanting, expectations, disappointments, hopes and rules. Music had some of that, to be sure, but you could always close the door, put on a pair of earphones, and just play. Or walk into a club where you’re known, pick up a guitar and sit in. You find a place for yourself. And can disappear into the beauty of the moment. Into harmony, which is everlasting.

So, getting diagnosed was a struggle. What the hell is this? What do I do? I haven’t had a doctor since I was a kid. I’m 57. My pediatrician retired thirty years ago. Both my parents are dead. Who the hell do I even ask?

He thought of calling Leslie then. But didn’t. Couldn’t. He didn’t want to know where she was or with whom. He didn’t want her to think he was sick. He just didn’t want to think about it.

The musicians’ union people knew a doctor who practiced out in the woods, a guy with whom they worked out some deal. Took Elliot two weeks to get in. The guy looked at him, heard the story, and started saying things like, do not pass go, do not collect two hundred dollars. He set up the blood tests and the CT scan and the MRI and made the connection to the cancer doctor, who is called an oncologist. The cancer doctor had grown up in Barrington and was the kid sister of one of Elliot’s band mates in high school. She knew all about Elliot. Apparently Elliot was some kind of hero to the people he had grown up with, the one person who stayed true to his calling, the one person who lived an authentic life. He had no idea. Lot of good all that was doing him now.

Chemo started. Radiation planned. The doctors presented him at their tumor board thing and argued about when and whether or not to do surgery. Spots on the lung ruled that baby out. And the money. It was all crazy. They wanted more money than Elliot imagined existed on earth. Five thousand for this. Ten thousand for that. Twenty-five hundred every time he had chemo, not counting the medicines themselves which were eighteen and twenty thousand dollars a dose. Of course, they never charge you in round numbers. They always charge you weird amounts, like $18,257.27, as if all the detail and decimal places make it okay that you have to pay for something that is only there to keep you alive, that makes it okay for someone to charge you to keep living after all.

Truth be told, Elliot didn’t know where all the money was going to come from. They were never going to raise enough with three nights of benefit concerts at The Urban. The DVD would have to go viral, and that just wasn’t happening. Forty years of playing in dive bars, playing good blues music and anthems that made people sit up and listen and then stand up and dance told Elliot that he had a lot but he just didn’t have the special sauce you need to sell a million of this or ten million of that and earn him enough so he could move out to Malibu and get a house on a cliff overlooking the ocean. Not that he would have wanted to move, if he’d hit it like that. These were his people. This was his place. His life.

The hospital people didn’t seem to mind, and he didn’t care about the money. They kept treating him and sending bills. He kept getting treated and paying little bits at a time, if and when he could. If and when his brain was clear enough of the drugs and the pain that he could write them little checks. Don’t ask, don’t tell, remember? He’d be gone soon enough. They could take his estate to court. His estate. One old car and ten sweet guitars. What a joke.

They went through a long set. The house was filled, and everyone was on their feet. People looked at Elliot with love and admiration. What could be better than that? You can’t see the crowd when you’re on stage, not really. Heads. Lights. Shapes. People dancing. You can’t really see but you can feel the crowd, taste the energy. Faces get to be a blur. Lots of familiar faces. But not who he wanted, not who he was looking for.

They took a break. Elliot walked through the crowd. People came up to him. They threw their arms around him, thanked him, blessed him, and touched him as he walked past. He made it look like he was going to the john. But nothing. She wasn’t there. Wasn’t coming. Wasn’t coming back. Even now. He didn’t want her back. All he wanted was to see her one more time.

Their last set was magic. As good as they were the first two nights, and as good as they were tonight, there was something different about that last set. All that love and longing, all the years and all their savage, disordered, dissipated, anarchistic integrity hit on that last set, which sounded more like a prayer than it did an anthem. We are one people. Free people. People who love and want to be loved just the way we are, the music said.

People were on their feet, but they stopped dancing. They just sang along, as if they were all lead singers, as if they all played guitar or all could blow on a sax until the music healed all wounds, until the boundaries that separated them completely dissolved.

Then he saw her. Leslie. She had come after all. She was standing in front of a pillar in the middle of the floor, stage right. She was standing alone, looking better than ever. But she was thirty feet away, with a guitar, a mike stand, a monitor, and fifty people between them, with the band in the middle of a song.

She looked better than ever, those clear blue eyes open to him and the world, her skin so clean it reminded Elliot of water. “You clean up pretty well,” Elliot always said, back when they were together whenever she dressed to go out. She had her hair up and she was wearing a blue, red, and gold silk scarf that made the room revolve around her, which made her stand out while everyone and everything else around her was a blur.

But she was thirty feet away, and not with him yet.

The band launched the last ballad, which was about Leslie, and Eliot sang it, right to her. He saw her lips move with his.

The problem when they were together was the way she disappeared, the way she lost herself in him. You can’t dissolve yourself. It is always hiding somewhere, feeling denied or angry when you can’t be it. It’s a huge problem when you can’t say and think what you want, and what you feel, and what you believe. He didn’t do that to her. He swore he didn’t. He wanted her to be herself, to be free, or that was what he believed. He loved her, and not himself. The problem was that she was afraid to be seen and she was afraid to love. And that he just didn’t know how to love one person at a time, completely and unconditionally, and that he certainly didn’t know how to love her.

Their last anthem was designed to leave the crowd on its feet. They weren’t doing encores. That was the deal. Not this time. Go out with a blaze of glory, so this would be a night everyone remembered. Go into the streets, they sang. Take back our world. Stand up together. Stand up now.

She sang with him. She knew the words better than he did. She could have been on stage with him again. Should have been.

And then they were done. He pulled off his guitar. She was just thirty feet away.

But the crowd won’t have it. They surged onto the stage. They stamped their feet and they kept singing. They touched Elliot’s face and hands and neck. He tried to push through, to get to Leslie, but they lifted him off his feet, hoisting him on a chair high in the air as if he were a king or a bridegroom. The band joined in. They kept playing and the whole house sang together. One body. One place. One people. Even if just for a few minutes, late one Saturday night.

When they put him down, she was gone.

Perhaps she had never been there at all.

Soon he’d be gone as well. The life he had chosen was full and rich. But the life he wanted had slipped away.

_____

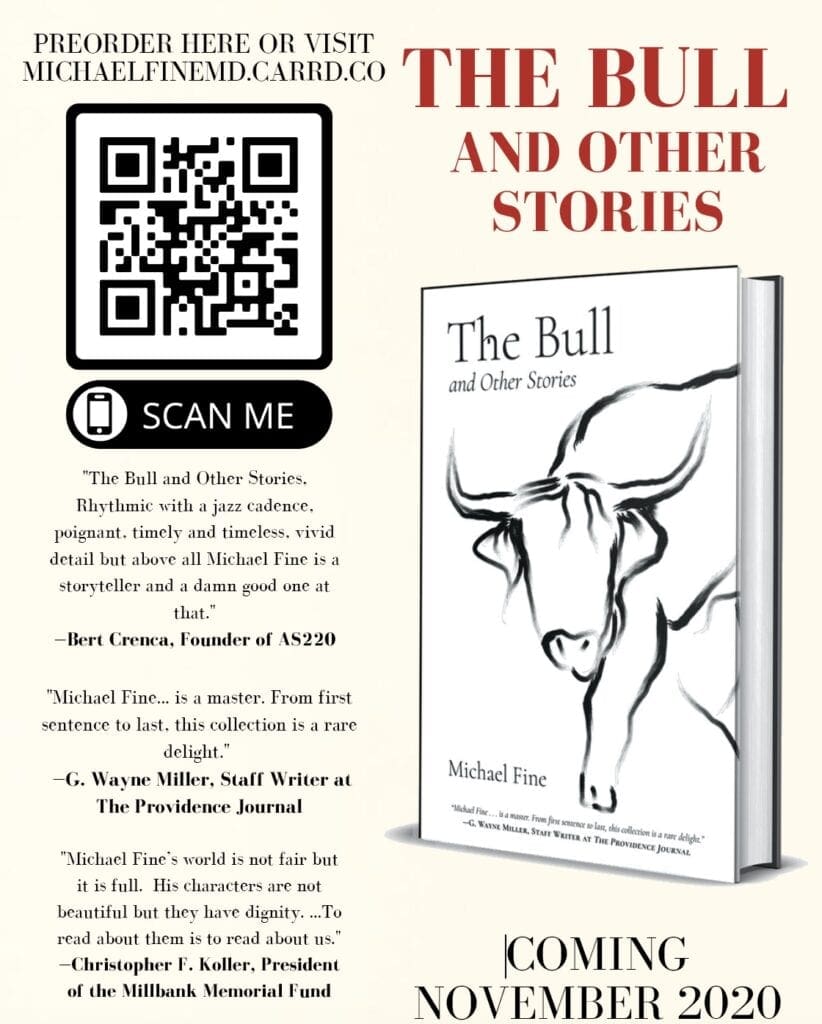

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here.

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor to Mayor James Diossa of Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.