Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 5, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 5, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 05.06.25 (Rental help, events, resources) – John A. Cianci June 5, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Rosemary-Lemon Statler Chicken, Yukon Golds, Haricot Vert and Dijon Demi June 5, 2025

- ICE arrests nearly 1,500 in Massachusetts. First part of “Operation Patriot” – Nantucket Current June 5, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 4, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

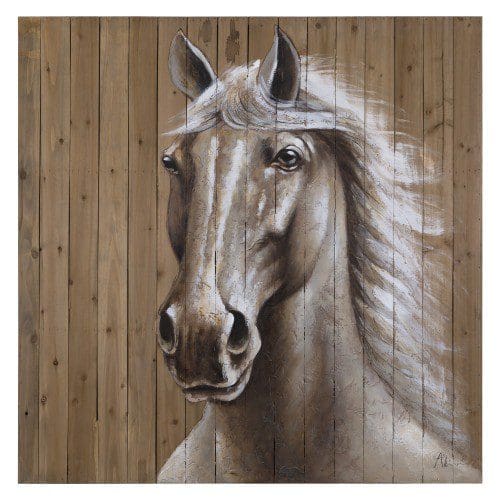

Awaking Horse – a short story, by Michael Fine

© 2020 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

She was a beautiful cream color, with a white tail and mane, a mare, and we remembered her blue eyes from before she fell asleep. We had great hopes for her. We would use her to take milk from the cows and goats to market, and also the vegetables that we grew on the farm in the spring and summer and split wood in the winter, and then there would be the money we needed to buy more animals and more land, and perhaps to build a bigger barn for more cows, and a bigger house. Then we might buy a carriage, and make a little more money yet, transporting our neighbors to the city, from time to time, or to the train station, or to see their families who lived just a little too far to walk.

But it all came to nothing. One day my father brought her back from the fair, where they buy and sell horses in a field outside the city once a month in the spring and summer at the full moon. Our father was riding on her bare back, and she was prancing, her head held high. We all came out of the house to see this horse and looked at her with astonishment and delight because she was so beautiful, and because she was ours. Then we took turns riding on her. Our father boosted us up, lifting each of us in turn by the armpits so we could throw one leg over her back and wrap our hands in her white mane, the hairs as thick as string and as strong as wood. Our father led her around the courtyard front of the house, and we each giggled or screeched with delight as we rode, holding on to her mane so that we didn’t fall off. When our father tired, he let me lead, and the new cream horse stood patiently as the rest of us helped the next child to clamber up on the cream-colored horse’s back. One of us went on hands and knees to let that child stand on our backs, and then we boosted that child with our hands wrapped together to hold their feet so we could lift them. Then we let that child put her or his feet on our shoulders as they rose higher and higher next to the patient horse’s back, until the lifted child was high enough to throw one foot over the horse’s back and sit upright, their hands entwined into the cream-colored horse’s white mane.

Children love with their whole souls, with abandon, and we loved the cream-colored horse in that way. We loved her so much that we all dreamed about her, and we took turns telling our dreams. Our father cleared a stall in the barn of old furniture and broken farm implements, and we decorated it with flowers, pine branches and herbs, so the home of our cream-colored horse would look as pretty as she looked and would always smell fresh and clean. None of us could imagine a better life.

But a few weeks later the horse fell asleep.

She didn’t die. She just didn’t wake up.

She just lay on her side in her stall. She didn’t move except to breathe, and her breathing was slow and heavy, as if she were dreaming heavy dreams of sadness or worry or remembering what she had loved and lost. Her stall smelled of vanilla at night and of the rich warm fetid smell of manure and horse urine in the mornings. Sometimes her tail switched in her sleep, as if she was dreaming about a pasture where the grass was long and green, the sun was strong, and there were insects flitting about in the then warm sunlight.

We thought she would die, at first, and a gloom descended on our household as thick as the sadness and despair we would have felt if one of us were dying, or if the country had gone to war. We didn’t play in the house anymore. When we played outside, we went far from the house and played quietly, so as not to wake the horse. Our father brought men to look at the horse, but they all went away, shaking their heads. They had never seen anything like it, and not one of them knew what to do. Soon, people began to avoid us, as if afraid that what had befallen our beautiful horse, and us, would also befall their horses and their families and loved ones.

And yet the horse lived. Every day, we brought hay and water, and left it in the stall. Every morning, the hay and water was gone, and there was a pile of manure in the corner of the stall. None of us ever saw her awake and stand. Her living and sleeping was a great mystery, a question for which we had no answer.

And so, we lived in the shadow of her sleeping. There was no horse to pull the cart to market, and no money to do the things we had been dreaming of. There was no horse to ride at twilight in the courtyard of our house, no way to us to take turns scrambling on her back and leading her in circles. We were left with the life we always had. We tried not to think about the horse, or the dreams she had let us dream. She lay in the stall in a dark corner of the barn, and we never went there, other than to bring her hay and water and to muck out her stall. The flowers in her stall wilted, the herbs dried, and the branches we put there lost their needles and fell from the walls. The barn became a dark place that we all tried to avoid.

Eighteen months came and went. There was, in fact, a war. Young men donned uniforms and talked bravely about battles and guns and how the enemy was very fierce and very evil. They knew they would be brave and that the enemy would be vanquished. But when they went away, only a few came back. We heard about others, who languished in hospitals in distant places, having been disfigured or maimed, and that made us very sad indeed. We were too young for the war, but we also counted the years — if the war went on too long, I would have to go, and that worried me, because I was not bold, not wont to see another people as the enemy, and not certain that battles and the slaughter of human beings could awaken the horse, or solved the problems we had on our farm, with our neighbors, or in the cities nearby.

They called our father to go to war, and we were afraid and very sad indeed. I was old enough and my sisters and brother were old enough to feed the cows and the goats and bring in the hay.

In that moment our childhood ended. We worked hard in the fields or tending to the cattle and goats whenever we weren’t in school. Our hearts stayed hidden, and our thoughts were always clouded over in that time, worried about our father, sad about the horse, empty because of the war, and hoping only that time would pass and that the world could right itself, so we could go back to laughing together, to clamoring up the horse’s back and leading her around the courtyard, shrieking with delight.

All this time the horse lay on her side all day long, breathing heavily, and deeply asleep. And we tried not to think about her.

One day our father came home from the war, wearing a tattered uniform. He was unhurt on the outside. But now he was silent. A certain weight was lifted off our backs, but our old life did not return. Our father went back to work in the fields, but he shut himself up in his room at night, and was short with us, where before he had been so warm and loving. We did not permit ourselves to dream.

And then one day we heard a whinny. The horse! We went running to her stall. She still lay on her side, but her eyes opened for a moment. And the smell of her was different. There was a new smell about her — a rich, languid smell, the smell of orchids and of pollens.

Then, for a few days, we heard snores and coughs from the horse’s stall. She was still asleep, but sometimes her eyes opened for a moment at a time. One of our sisters said she thought our mare was in heat.

Three days later, just before dawn, we heard whinnying, not once or twice, but one call after the next, as if our horse was alive again and was whistling a tune, so loud and clear it felt like we were dreaming again. We shook ourselves out of our slumber and our warm beds and went running to the barn. It was a cold clear morning, and the long yellow rays of first sun angled through the bare trees across the courtyard. The birds had come back and were calling to one another as they flitted from place to place, and the chickens in the yard had clustered about, waiting to be fed.

The horse was awake and standing on her feet. Her eyes were dull, as if she wasn’t fully awake yet, but great clouds of steam flowed from her nostrils as her warm moist breath flowed into the crisp morning air. It was unbelievable. She blinked as if she didn’t quite recognize where she was or why she was here, or even what she wanted yet. But she was awake, and she was standing on her own.

We crowded around her, wanting nothing more than to touch her warm flanks, to pet her warm strong neck, or to touch the soft spots around her mouth and nostrils, which were black in color and as soft and warm as porridge.

Then our father came and shooed us away. He stood silent and looked at the horse, face to face, his breathing also making tiny clouds in the crisp morning air. Horses don’t look you in the eye the way a person does. There isn’t the same fix and focus. They take you in as part of the scenery, as one tiny perceptual fact in a broad bright world of colors and shapes, which they see themselves as part of without perceiving self and other as we perceive it, as if time and nature were part of one continuum, as if there were no future, no past, and no memory, and no hope of change but only the strange threatening majesty of the present.

I don’t know what our father wanted to learn from the horse. Perhaps he only wanted to know if he could trust her to remain standing and awake, to find out if she who had disappointed him and us so intensely could ever be trusted with his and our hopes again.

It didn’t matter. He reached out and patted her nose. Then he went into the kitchen, and made her a mash of warm milk, oats and molasses, which he brought out to her in a bucket, and which she hungrily and enthusiastically consumed, licking the corners of the bucket with her tongue to sop up every drop, as if she were a cow.

And then our father put a rope halter around her head, and led her out into the courtyard, into the sunlight. The cream-colored horse walked gingerly, slowly, as if she wasn’t sure of the location of her feet, and when she came out of the barn she blinked and appeared dazed. But she followed our father diligently, not sure of herself but trusting him, the rope that tugged on her muzzle guiding her gently forward.

Our father found a second lead rope in the paddock and clipped it to her halter. Then he passed each lead rope around a different side of her neck, so he had reins with which to steer her. Then he got up on a mounting block and leapt onto her back.

All of a sudden, the old cream-colored horse we knew, the horse we hoped for and loved, was returned to us. The horse held her head high again. The brightness came back to her eyes. She trotted out of the courtyard, lifting her feet high, almost prancing.

Our father came back two days later, leading the horse. He put her back into her stall, which we decorated again with flowers and herbs and pine branches, and he brought her mash every morning, mash he made himself, and he patted her neck as she ate it. He pulled an old horse cart that lay covered with dust and cobwebs from the corner of the barn, painted it bright orange, and began to bring milk, butter, and cheese to market once a week. Before he set out, we covered the cart in flowers, and wove flowers into the cream-colored horse’s mane and tail.

A year later, when we had almost forgotten our long period of sadness while the horse slept, we heard a whinny in the night, and then a second, very weak cough. We all jumped out of bed and went running out to the barn. By lamp light we saw the new foal, wet from her mother’s womb. The foal was jet black and struggling to stand.

All at once we were in love again.

Now we are the owners of horses. We pamper them with mash and fill their stalls with flowers, because we remember when our horse slept, and our lives were without feeling and hope.

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Join us!

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor to Mayor James Diossa of Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.