Search Posts

Recent Posts

- ART! Annual Art in the Village pairs with new Dads, Grads and Art weekend at Mistic Village June 10, 2025

- Device developed in Rhode Island a breakthrough in pediatrics – the SMöLTAP® Positioner June 10, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 10, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 10, 2025

- Papitto scholarships and $1 Million investment in idea of Cranston’s Melissa Gonzalez Gutierrez June 10, 2025

- URI student-athletes, recent alumni start Summer Soccer Camp, NextPlay Training – John Cardullo June 10, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Aborting the Menokin legacy

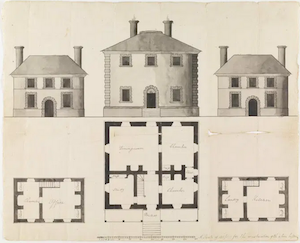

Photo: Menokin House as it will look when rebuilt with “deconstructed” elements. (Menokin Foundation)

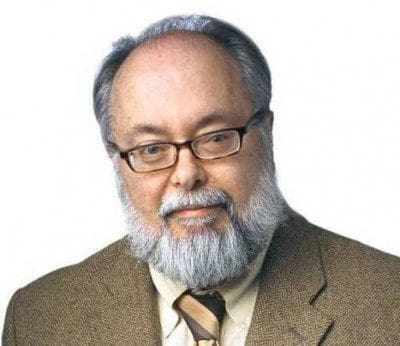

by David Brussat, architecture writer, Architecture Here and There

Menokin House, near Warsaw, Va., was built in 1769 by Francis Lightfoot Lee, who received the plantation’s land as a wedding gift. He was the brother of Gen. Lightfoot Harry Lee of Revolutionary War fame, and the uncle of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. The mansion is the only remaining unpreserved home of a Virginia signatory to the Declaration of Independence.

Menokin in 1965. (Calder Loth)

If its “restoration” goes forward as planned, it will remain the only such unpreserved homestead. Its beauty and its legacy, however, will be condemned to oblivion.

In online discussions about my last post, “A preview of the E.O. era?,” a link to a website devoted to the Menokin “restoration” was offered to exemplify changes even worse than those proposed for the Federal Reserve Building, in Washington, D.C., whose beauty is at risk from an expansion using glass curtainwall.

Just look at the image on top of this post. That is what’s in store for Menokin. Can anything worse be imagined?

I have railed for decades against a shibboleth of the historical preservation movement that changes to historic buildings should not look like the original. The idea is supposedly to preserve the original’s “integrity” by differentiating the new from the old. It is a bogus idea – a preservationist principle masquerading as a job bank for modernist architects. The goal of differentiation can be achieved more effectively with signage. For example, “House built in 1810; new wing added in 1965.”

Original design with outbuildings. (Foundation)

An article on Menokin in the online journal designboom (no initial cap) only reinforced my objection to forced differentiation. It described in laughable terms the ongoing “Glass House Project,” as it is called, an effort to “reimagine” Menokin – largely a ruin today – as a center for the study of historic construction and preservation techniques.

The intention is unobjectionable, but under the auspices of the Menokin Foundation, which owns the mansion and grounds, the project has, it seems to me, gone off the rails. Instead of restoring the house to what it looked like in, say, the time of Francis Lighthorse Lee, they are, for no apparent reason, framing much of it in glass, including the corner that collapsed in the 1960s. That is a shame and a betrayal.

The designboom article and its description of the project invite ridicule. The magazine rejects the use of initial caps in proper names and at the beginning of sentences, as if such textual decapitation atones for the magazine’s – what? – its white designer privilege? Never mind that. Just read the description of the project by author Philip Stevens (oops, philip stevens):

the glass engineering, led by eckersley o’callaghan, blends with the 18th century stone, brick, and timber. while traditional restoration methods cover evidence of the human story that historic structures present, the transparent design seeks to emphasize the deconstructed architectural elements of the building and provide a literal window into the lives of those who built, lived, and worked at menokin.

The project’s glass “blends” with the “18th century stone, brick, and timber”? No it does not. Traditional restoration methods “cover” evidence of the building’s story? No they do not. Will the “deconstructed” house tell its human story better than a reconstructed one? Not likely. Will the glass “provide a literal window” into the lives of its occupants? Hardly. The whole article by Stevens is a farrago of falsehoods and inanities. After reading it, I was all revved up to heap justifiable abuse upon the project.

And yet the fact that it has been supported by Calder Loth, the eminence gris of Virginia’s architectural history, gave me reason to pause.

Menokin as ruin. (Foundation)

In the mid-1980s, he received a letter from a woman who then owned Menokin, seeking his help in saving the house. “What led to her call,” writes Loth in a 2006 lecture to the Virginia Historical Society, “was a letter from the National Park Service informing her that the Park Service was considering removing Menokin’s National Historic Landmark status because of loss of integrity” arising from years of abandonment and deterioration.

Now the very plan to fix it up proposes a major loss of integrity.

Loth pitched in to help. But by 2006, he states, the Menokin Foundation’s goal “was not to restore the house and develop it as a conventional house museum. Stabilization and restoration of the ruin could take place not as a goal but as a process.” Techniques used in the process would not only be applied but exhibited as educational tools. It seems to me that as of 2006, the goals of education and restoration were not necessarily incompatible. Loth stated: “Panels can be removed as various original features are put back. I think this concept has a lot of merit.” He remains an honorary trustee of the foundation and a supporter of its Menolin project.

In an email to an online classical discussion group this morning, Loth wrote that the project “will not be an aesthetically beautiful work of architecture, but a special and, we hope, an intriguing educational facility.”

Menokin under temporary shed.

Yet Loth in his 2006 lecture describes how much of the original Menolin House and stored interior woodwork remain. The record of its original design and construction is considered the most intact and extensive of its kind. The exterior could be rebuilt to its original design (Lee’s architect is unknown), using both original materials or historical fabrications as necessary. The interior could be rebuilt as well, and while almost all of the original furnishings are lost, they too can be replaced. Nor need the project sacrifice any of its educational exhibits. They can inhabit the rebuilt rooms or new or existing outbuildings, which should also be restored, if necessary, or designed to fit into the setting. Such a balance should be the task of the trustees and hired professionals.

There would be no need to abandon the goal of displaying how the house was originally built, how it was rebuilt in the 21st century, and its historic occupants – Lee, his family, his slaves and the natives of the Rappahannock tribe who were the original stewards of the surrounding landscape. These goals can and should be preserved by the foundation.

Construction on the project is at an early stage such that its design, by Machado & Silvetti Associates, of Boston, could be reconceived and recommenced. The result would be a house that shelters an educational center but looks like the colonial house of the Lee family both outside and, to some extent, inside. Such a plan would accomplish all of the project’s goals without sacrificing Menokin’s authenticity, beauty and legacy to the ego of architects and to some, perhaps, but surely not all of the trustees and staff.

Surely if the Menokin Foundation’s intention is to save the house and render it useful to the broader projects of history and historical preservation, they should be eager to be rid of the plan’s artificial architectural elements and instead honor Menokin’s place in American history. Or, in these days of rage and absurdity, an argument could be made to destroy Menokin in order to atone for its place in history. Unwittingly, that is already being done.

Menokin plantation landscape. House and outbuildings, lower left. (Menokin Foundation)

For the full article: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2020/06/18/aborting-the-menokin-legacy/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/