Search Posts

Recent Posts

- A crack in the foundation – Michael Morse June 8, 2025

- Ask Chef Walter: Ultra processed foods – Chef Walter Potenza June 8, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 9, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 8, 2025

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

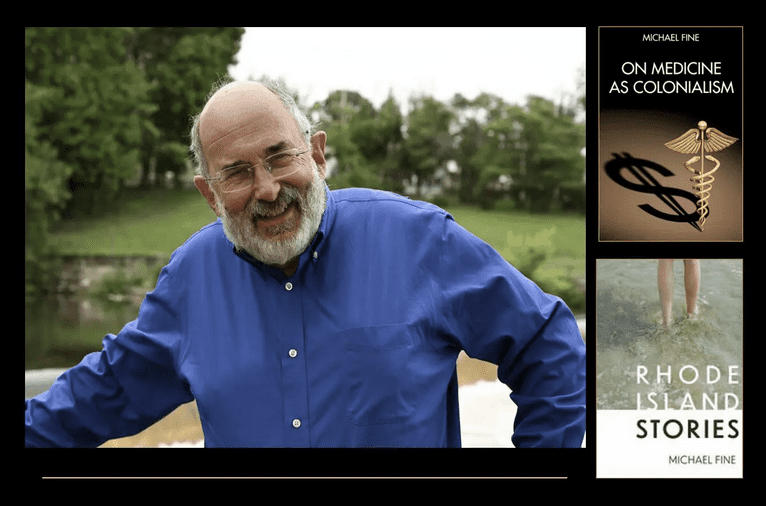

A Waif – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

He was tiny, almost too small to be standing. But there he was standing and walking, just a slip of a child, dark skinned and so thin you could see all his bones, his ribs sticking out, his forehead big and shiny and pronounced because the soft places in his temples had shrunken. He had huge dark brown eyes which glistened as he looked about, and he was always looking about, ready to dart out of the way, to find the shadows, to try to disappear. How old was he? He was the size of a three-year-old, but he moved with the conviction of a much older child. Six? Seven? Even eight? Where had he come from? How had he found his way to our barn? to the pallet of moldering hay, which remained long after the donkeys and the cow and the goats were gone.

There were chickens in the barn of course, scrawny chickens which skittered and clucked as they raced from place to place, the slanted fall afternoon light sparkling with the dust they raised as they flapped their wings when they ran. The barn still smelled of manure and earth and of that moldering hay. It was a rich, wise smell of a long ago time, when there was peace and when the land was filled with farms and animals, and people went about their work, raising cows, sheep and goats, growing wheat and corn, filling the land with the wealth of people who lived one life together, together with their animals and the land itself, when the earth was rich, dark, and productive.

I ignored him for a day or two. The barn was no longer used. We stopped trying to find the chickens’ eggs that were buried in the straw once the door of the chicken coop broke and the chickens scattered, making nests in the straw or roosting at night in the rafters, away from the cats and raccoons. The children went in sometimes, to play or to try to catch a chicken whose neck their mother would wring, on its way to being plucked and roasted for dinner.

It is often useful not to see and not to think, in this time of trouble. There is only so much one man, one person can do. He wasn’t hurting anyone by being there. God himself only knew what trouble there had been in this waif’s life, like the lives of too many who drifted from place to place without homes, without families, without parents, love or protection. He was alive. Let him be, I thought. He isn’t my problem. Or my responsibility.

Sometimes I saw him in the town, begging on street corners or in the marketplace. Better he sleeps in our barn, despite the dust and the loneliness. Better that no one knows where to look for him. Better that no one finds him. He’ll be gone before long. He’ll move on. Find a corner of another abandoned building. Or keep running from whatever it is he had run from already.

He’s so small, I thought. And so alone.

So I went out to the barn early one morning to find him, but he was already gone.

I came back in the evening. But he wasn’t there then either. The chickens were roosting in the rafters, other small birds flittered about, and there were mice racing from place to place between the walls and under the hay. But no evidence of our visitor. Still, I knew he was sleeping there. I would catch a glimpse of him from time to time, slipping out into the street from behind the fence that had once held the cows in, or I’d see him darting from shadow to shadow, as if he had learned how to move from the mice. If I came out to the barn to try to find him, he would never be there. He had learned to hear me coming, and he’d slip away.

People began to talk. They had noticed him around our place, which made them wonder about me and about us. Were we keeping him there? Why? Who was he? Was he a child we had abandoned? a street urchin we had found on the street and were misusing? or the child of a distant relative we had taken in and were abusing? What was in it for us? Did this reveal something about me, or us, that no one knew — some secret dark flaw — that made me and us like everyone else, everyone who was corrupt or violent, each in his or her own way. We acted so high and mighty. There it was. We were no different, despite our high ideals and all that fancy talk.

Then a group of five people came to the house one night. They stood on our porch as the sun was setting. It was fall. Half the trees had lost their leaves, and so brown and drying leaves were scattered over the ground and rustled when you walked through them. The air was sweet with the sugars of their decomposition. The sun lay low in the sky, which meant I had to shield my eyes to see the people who stood on the porch with me.

“Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” one man said. He lived a few houses away, had short graying hair and worked as a firefighter part-time.

“I don’t know what you mean,” I said.

“There is a child living in your barn. We’ve all seen him,” a woman said. She was thin, with short-cropped salt and pepper hair. She lived down the hill. She walked by our house with a small dog every day at two o’clock.

“I’ve seen him too,” I said. “But I don’t know who he is or where he came from. I worry about him. So small and so thin. He is way too young to be out there on his own.”

“Times are hard,” a young man said. He was the best put together of the bunch. Thin and standing erect, he was on the town council and always seemed to be the voice of reason in town.

“That’s no excuse,” the woman said. “You’re responsible for everything that happens at your place.”

“I don’t know what else to do. He’s a child. I haven’t been able to catch him. I’d love to get him to someplace self and warm. But…”

“Lock your barn. Lock your gates. Someone will see him and report us. You’re attracting too much attention,” another woman said. She was pear-shaped, with long blond dreadlocks that seemed inappropriate for a woman of her age.

“I can’t throw a child into the streets,” I said. “I don’t know anything about him. Surely we can find another way.”

“Do it,” the first man said. “Just get it done. You take care of us. We take care of you. That’s how it works.”

The others looked straight at me. No one disagreed. Their message was clear.

“I’ll think about it,” I said.

“Do it for yourself or we’ll do it for you,” the thin man, the city councilor said. His voice was hard this time, which surprised me, as I had always regarded him as a voice of reason.

They filed off the porch and down the stairs, one after the next, without shaking my hand or saying goodbye.

This is more serious than I thought, I said to myself. Look what we have come to.

But I did what I was told. I put a latch on the inside of the gate and a padlock on the barn door. And then put the whole situation out of my mind.

Early one morning I saw the waif again. He came from behind the barn, hopped over the fence and then disappeared into the woods near the dry riverbed, headed into town. Truth be told, I was relieved to see that he was okay, that he had found a way to survive, no thanks to me. I’ll look away, I told myself and pretend I hadn’t seen him. There’s a window in the barn, I thought. He must have found a way in through that.

I went about my business and kept my fingers crossed that no one else had seen him.

But that was not to be.

A few days later, the group of five was back on my porch.

“You are lying to us,” the pear-shaped woman said.

“You didn’t do what you promised,” the part-time firefighter said.

“Playing games,” the city councilman said.

“We’ve had it with you,” the pear-shaped woman with blond dreadlocks said.

“Whoa. Whoa. Whoa,” I said. “We put a latch on the gate and a padlock on the barn door. Just like you asked. What more do you want me to do?”

“Do whatever is necessary,” said my next-door neighbor, an angry man with big ears and short-cropped salt and pepper hair. “He’s back. And you know it. You’ve seen him. We know you have. You are putting us all at risk.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. He’s a child,” I said.

“See! That’s what I said. He’s not like us. Puts his wild ideas about some street kid in front of the safety and security of his friends and neighbors.”

“You don’t know anything about him,” the city councilor said. “You don’t know where he is from or what he intends.”

“He’s a kid,” I said. “He’s out there all alone, scrounging and scraping just to stay alive.”

“So you do know he’s at your place. Sounds like you know a lot more about him than you are letting on,” the pear-shaped woman said.

“I don’t know him from Adam,” I said. “But just look at him. He’s this scrawny little kid. On his own. What do you expect?”

“We expect security and freedom. As much as we can get. Understanding the world in which we live,” the town councilman said.

The five of them shook their heads and walked down the stairs, in single file, and then walked away from the porch five abreast, filling the street as if they owned the world. The wind blew the leaves around, stirring up little whirlwinds of leaves in corners and on porches and next to stone walls, and a light rain began to fall.

I didn’t sleep that night. There were no good options. I had already made myself a kind of public enemy by pretending not to see what I saw, and by pretending that none of this was my problem.

I went out to the barn in the morning, the first time I had been there in weeks. The barn roof curved groundward in the center like the swayback of a worn-out horse. You could see sunlight through the cracks between some of the barnboards, which were withered and brown with age. The fencing around the old paddock was broken down in most places, the fence posts in a line like gravestones, and the ground where horses and cows once stood was dried and cracked, so nothing grew there, not even the goldenrod and Queen Anne’s lace, and thistle that had taken over the pastures and the old hayfields.

I unlocked the padlock and slid the barn door open.

The glare of sunlight from the window, and the lines of sunlight bursting through the cracks between the boards made it difficult to see at first, the air filled again with a silver dust that glinted and sparkled in the sun. The window was closed. There was no evidence of human habitation on pallets where the old hay lay moldering, nothing like a bed or a nest built out of the hay, which was what I expected to find. There must be some mistake, I thought. That boy isn’t here. He must be staying someplace nearby but not at my place. I am off the hook.

But then I noticed a red garment draped over one of the stalls in the back of the barn.

Inside that stall, someone had created a tiny house for themselves. An old cot with a mound of blankets on it. An orange crate on its side, which functioned as a table. A stump trying to be a chair, next to the orange crate. Improbably, there were books strewn on the table. And tacked to the wall, an old photograph of three people, a man, a woman, and a child, the child sitting on the man’s shoulders.

How had this kid gotten inside my barn? Then I saw, on the outside wall, a place where one of the barnboards had rotted away close to the ground, and when I went to test that place, three boards came off in my hand, three boards which together made a small door that could be taken off and secured again from the inside.

Then I heard a noise above me. The boards that made the floor of the hayloft creaked. Just a little. One step. Then a pause. Then another step. As if something or someone was moving very carefully, moving slowly to avoid being noticed.

I’ve got you now, I thought, and I spun around, out of that stall, and raced up the ladder to the hayloft, a ladder I had climbed a thousand times when the cows were still here, in winter in the morning and evening to throw down hay and keep those beasts alive.

Suddenly one, and then two of the rungs at the top gave way as I stepped on them, and I fell.

Fifteen feet.

I landed on my feet and then fell to my back on the cold dirt barn floor.

When I came too, I could barely move. One of my legs was broken, the bone piercing the skin, my pant leg wet from the blood, which was now cold, and my boot filled with blood. As I crawled on hands and one knee out of the barn, dragging the broken leg behind me, I saw that that stall which had been used as a room and a refuge was now empty, and that the waif was gone.

The waif was never seen around my place again. He appeared from time to time over the next few weeks, under porches or hanging in the shadows of the town, and once or twice was seen coming out of the yard of the town councilor just before dawn. But then he disappeared, and we never saw him again.

When my leg healed, I brought the ladder down to check the rungs. Sure enough, those top two rungs had been sawn half through, so they would break with the weight of a man.

I meant that child no harm, that morning when I almost caught him. I had resolved to stand up to my neighbors, to give the boy decent clothes and a place to stay, and then send him to school, when the schools reopened. I imagined taking him fishing and could picture him sitting on my shoulders as we walked home at twilight.

But that, and too much else, was not to be.

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.