Search Posts

Recent Posts

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 12.06.25 (Memorial Day, Vets Cemetery, Events, Resources) – John A. Cianci June 12, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Mediterranean Seared Salmon, Olive Tapenade, Artichoke Hearts, Roasted Red Pepper Tahini June 12, 2025

- Why more Rhode Islanders are choosing Heat Pumps over traditional AC this summer June 12, 2025

- CNAs to be trained at URI in administering medication in state facilities June 12, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 12, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 12, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

A devoted family meets a ‘broken’ system of care for Alzheimer’s – Ocean State Stories

This story is published in partnership between RINewsToday.com and Ocean State Stories, a journalism initiative at Salve Regina University.

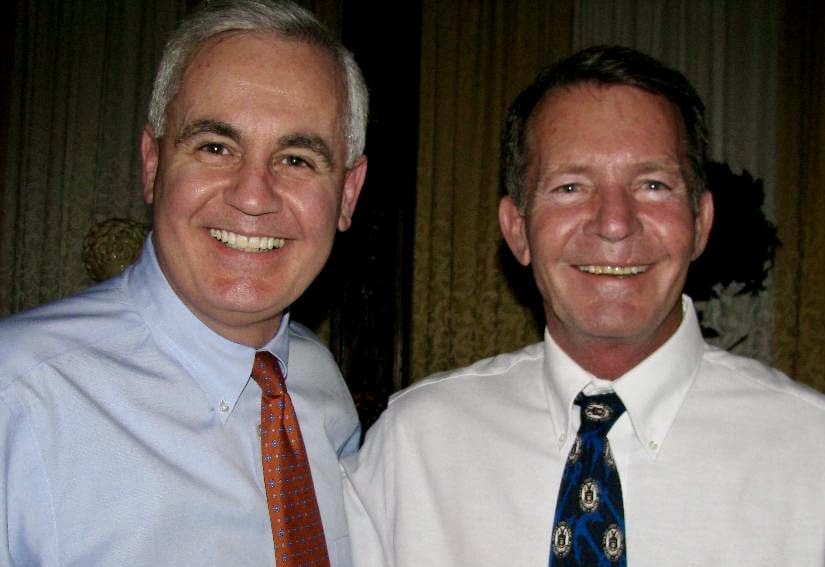

Photo, top: Roger Begin, left, and brother Richard – Submitted photo

As the incurable disease moves him toward inevitable death, the stress on him and his devoted family becomes overwhelming. A story shared by thousands of Rhode Islanders — and the numbers are mounting.

Part One

The first signs of the disease that would claim the life of Richard Paul Begin began to surface a few years before his death at age 74 on Feb. 14.

“He was a voracious reader, he would plow through three or four books a week, and then probably about five years ago, we began to notice that he was not reading as much,” his brother, former state representative, State Treasurer and Lt. Gov. Roger N. Begin, told Ocean State Stories.

“He would do crossword puzzles and things like that and he began to not do those things. And it became evident that he was having some memory issues.”

Married, the father of two children, grandfather of six, and member of a prominent Woonsocket family, Richard had retired from a successful business career and was dividing his time between Rhode Island and Florida. For a while, Roger said, those close to him “didn’t make a big deal out of” the changes they observed in the man.

But eventually Roger made a suggestion to Richard’s wife, Judy.

“I said, ‘even though we all know what he’s dealing with, we should probably have him meet with a neurologist to actually put a name on it. I don’t know if it can be treated at this point, but let’s go to a doctor.’ ”

Roger, a member of the board of directors of Lifespan, the state’s largest healthcare system, made an appointment with Dr. Brian Ott, who was director of Rhode Island Hospital’s Alzheimer’s Disease & Memory Disorders Center.

“He confirmed that what my brother had was Alzheimer’s,” an invariably fatal and incurable condition, Roger recalled.

What followed was a progression toward the end stages of the disease that left Richard increasingly frustrated and disturbed – and his family correspondingly stressed as his needs mounted. An ordeal no one should have to endure was underway.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, an estimated 6.7 million Americans aged 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s (although studies are limited, researchers believe that about 200,000 Americans ages 30 to 64 have younger-onset Alzheimer’s). Barring medical breakthroughs to cure, prevent or slow the disease, the association projects that by 2060, nearly 14 million Americans will have Alzheimer’s.

The latest statistics from the Rhode Island chapter reveal that 24,000 state residents aged 65 and older lived with Alzheimer’s in 2020. That number is projected to rise to 27,000 in the year 2025, an increase of 12.5%. In 2019, the last year that mortality data was available, 456 Rhode Islanders died of the disease.

Speaking with Ocean State Stories, Rhode Island chapter executive director Donna M. McGowan described the toll the disease exacts on family members and others who care for people living with Alzheimer’s – care for which they are not paid. There are an estimated 36,000 unpaid caregivers in Rhode Island, according to the local chapter.

“We know that 54.2% of our caregivers are suffering with a chronic disease because of the stress,” McGowan said. “And we also know that 41% of our caregivers have been diagnosed with depression and 11.5% of that population is living with a very severe physical condition. In other words, they’re not able to or won’t be able shortly to take care of their loved one because they’re too sick to do it.”

But until sickness incapacitates them, McGowan said, caregivers typically don’t give up.

“This caregiving ‘job’ in the world of dementia becomes 24/7,” she said. “And we think we can manage it. We want to save them, right? We want to do everything we can. We want to keep them at home, we don’t want them going anywhere else. We want them to have a really good quality of life and that’s just not the way this disease shakes out. So, at times, we at the association worry more about our caregivers.”

The Rhode Island chapter is there to help, McGowan said.

“We provide a plethora of help,” including a free helpline, 1-800-272-3900, that is answered around the clock, every day of the year.

“Maybe you’re calling because you want a list of neurologists or a list of geriatricians that specialize in dementia. We can give you that information. We’re a repository of information. On the other end of that phone are licensed clinicians, [professionals holding Master of Social Work degrees], and they’re licensed to counsel and walk you through any questions you may be having in the moment.

“So if you call at two o’clock in the morning and your loved one is starting to wander and you’re trying to pull them back in the house or they want to drive a car but they can’t drive – we can walk you through what to do, and what not to do, right? Even if that means you’ve got to call the police, you’ve got to call the hospital, whatever it is.”

Among the many other services the Alzheimer’s Association offers are a resource directory, a guide to how Alzheimer’s affects the brain, risk factors, risk-reduction measures, an explanation of early signs and symptoms of the disease, research updates, links to opportunities to participate in clinical trials, a list of treatment options, and connections to support groups.

As his Alzheimer’s advanced, Richard Begin’s emotions harshened and his needs mounted, increasing the stress on his family.

“When we were like ‘Richard you can’t do this’ when he wanted to do something and we resisted he could get quite angry,” his brother recalled. “And he was physically strong enough to be physical about it. In hindsight you look back and say, ‘it was a different person who was reacting.’ But that was one of the challenges.”

During a stay at Rhode Island Hospital, it was determined that Richard could no longer live at home. He was discharged to an assisted-living center that Roger describes as “a very, very nice private pay-for facility. Fortunately, he had the resources to be able to afford this. And they did a fine job with him.”

For a while, that is.

“His condition declined over a period of about five months or six months and they said that the kind of care he needed they were not able to provide. That’s not what they’re designed to do,” Roger said. “So they said, ‘he really needs to go into a nursing home.’ ”

Finding a quality home that would admit him proved problematic. The Begins could afford the best, but when some prospective placements saw Richard’s record and the medications he was taking to control his behaviors, they declined.

“We ended up having to go to a nursing home that was not our first choice,” Roger said. “It was a tough fit. They were not staffed professionally and number-wise to be able to deal with patients like this.”

Richard stayed at the home for two months as his family renewed their hunt for a superior home.

But as they would discover, they had exhausted their options.

___

Part Two

Former State Treasurer and Lt. Gov. Roger N. Begin: ‘Only when policymakers feel the impact of this broken system for their own families may there be reforms and funding to fix it.’

Distinguished Alzheimer’s disease scientist Lori A. Daiello began her career on the frontlines of care. It’s a career that brought her to cutting-edge research today at Rhode Island Hospital’s Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders Center, one of two such centers in the state nationally recognized for Alzheimer’s research and treatment.

“The first 20 years of my career were spent working with older adults with cognitive impairment in the community: nursing home patients and older adults with cognitive impairment in assisted living,” Daiello told Ocean State Stories. “And that’s what led me into research.

“So I came here to Brown to do a fellowship and I stayed at Rhode Island Hospital and continued into research because of that very informative experience early on in my career. I saw up-close and personal the devastating effects on the family, the patients, the [family] caregivers, the paid caregivers. It almost defies description.”

The toll on families was recently brought home to Daiello, literally.

“My mother-in-law has dementia, and we just moved her here from San Francisco,” Daiello said. “My husband’s a therapist and I’ve been doing dementia work for 37 years. We are the most informed people you could imagine. And having to confront this, how we have struggled — this is what gives me such fire about research.”

The research is substantial.

Directed by Dr. Chuang-Kuo Wu, the Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders Center offers diagnostic and treatment services such as those Richard P. Begin, brother of Roger N. Begin, received. The center conducts clinical trials, including a landmark study of lecanemab, sold by Biogen and its Japanese partner, Eisai, under the brand name Leqembi. The drug, which slows cognitive decline but does not cure Alzheimer’s, received full federal Food and Drug Administration approval this month.

Prevention is also being researched at Rhode Island Hospital and elsewhere, Daiello said. Of keen interest: the association of healthy hearts with healthy brains. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the so-called Project TEACH (for Tailored Education for Aging and Cognitive Health) seeks to learn if healthy lifestyle habits such as diet, exercise and not smoking, which benefit the heart, can also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

Emerging evidence suggests they do. Hypertension is also suspect, according to Daiello.

“Uncontrolled high blood pressure may contribute vastly to your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease,” she said. “We’re starting to understand more about this: what I call almost a doomed partnership, Alzheimer’s disease pathology along with vascular problems in the brain. And we think that both together are probably very important in figuring out who’s going to develop Alzheimer’s disease or not.

“Taking care of your heart, your cardiovascular system, is very important for brain health, but when you talk to a community group of elders, they’re just, ‘it’s your heart, it’s your blood pressure, what’s it got to do with my brain?’ So, we need to get people thinking in this more holistic way about how their general health affects the risk of getting Alzheimer’s.”

Daiello said that researchers are “even seeing this connection in people who develop cardiovascular disease prominently in midlife… people in their 30s, their 40s. A lot of these folks are Black, they’re people of underserved communities, and they may not have great access to healthcare as their cardiovascular disease gallops forward.

“They also don’t have an understanding about how controlling this part of their health early on may affect their brain health. We have this data from studies — we just need to get people thinking about it and taking it seriously and taking charge of their own health.”

Having experienced first-hand the difficulties of caring for a loved one with dementia, Daiello understands the support families need but do not always get to reduce stress and keep loved ones at home as long as possible.

Daiello said that studies have demonstrated success is possible with programs that “help families understand what they need to help their loved one function best. What type of care do they need? What type of diagnostics would work best for them? What type of in-home care might be available and affordable for them?”

Such programs exist, in pilot fashion, the scientist said, and they are successful. With them, “generally, the patients go to nursing homes later, the families have less caregiver burden and less stress and really it just works better for everyone. But these types of structures will require creative funding,” which does not exist.

The funding issue also frustrates Dr. Edward D. Huey, who in February succeeded Dr. Stephen P. Salloway as director of Butler Hospital’s Memory and Aging program, Rhode Island’s other leading Alzheimer’s research and treatment center. Butler is operated by the state’s second-largest healthcare system, Care New England.

A Q&A with Dr. Stephen P. Salloway, founding director of Butler’s Memory and Aging Program

“The system is very poorly set up for these patients on every level,” Huey said. “The fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for out-of-home placement means people have to spend down to get onto Medicaid and give away their assets. There are all these little quirks which are historical and I don’t fully know all the reasons for them but they’re very badly set up for patients with dementia.”

Huey spoke with Ocean State Stories from New York this spring while he was splitting his time between Butler, in Providence, and Manhattan, where he was director of the Frontotemporal Dementia Center at Columbia University and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology in the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain. He has since moved full-time to Rhode Island.

“I see a fair amount of early onset dementia,” Huey said during the spring interview. “With this class of patients, they start acting strange and because they’re relatively young no one thinks of dementia. Then they get fired from their job and six months later, people start to clue in that they’re demented and they come to see me.

“But at that point, they’ve lost their insurance. So I can’t even order an MRI scan because they can’t afford it. They don’t have health insurance, they’ve lost their job, and a lot of them are losing their house and none of it’s their fault. So you’ve got a family that’s dealing with this new diagnosis and at the same time, they’re going bankrupt because of it.

“It’s really unfair. It’s a tragedy.”

Richard Begin’s condition continued to worsen during his two-month stay in a nursing home, and it was soon evident to his family that the facility was not equipped to provide the advanced care he needed. Unsuccessful in their search for a nursing home that could, Richard’s family arranged for him to be admitted to Butler Hospital.

The staff there managed to stabilize Richard, and when they had and he was ready for discharge, another search for a nursing home began. But as it was being conducted, Richard’s illness deteriorated precipitously.

“He was staying in bed and was not taking in nutrition anymore, thus leading to their conclusion that he was approaching his final days,” brother Roger N. Begin recalled.

Richard was discharged to HopeHealth Hulitar Hospice Center in Providence, where, Roger said, “they did a fine job. And he passed within a matter of days,” on Feb. 14 of this year.

In reflecting on his family’s experience, Roger has reached stark conclusions about how individuals with Alzheimer’s and dementia are treated – and he places them in the context of a broader societal issue, ageism.

“The way we view aging and the way we treat it holistically — not just Alzheimer’s or dementia, but holistically — we just close our eyes and say, ‘well, you know, they’re just old people.’ Ageism is part of the problem.”

Roger’s long public service – a decade as state representative, four years as State Treasurer and four years as Lieutenant Governor – has uniquely informed him about some of the underlying political realities.

“Having come from a background where I spent several years of my life in helping to shape public policy, there’s no advocacy, no voice there,” he said. “Where’s the loud voice going to come from? This is a very vulnerable population that we’re dealing [with] that is not able to express themselves in a way that will be heard.”

Although not familiar with the specifics, Begin acknowledged the advocacy work of organizations including the Alzheimer’s Association and AARP.

But they alone will not be able to bring reform.

“As I have observed about my experience, the caregivers have all been wonderful,” Roger said. “It is the system of care that is broken. And the numbers needing care during the next twenty years will grow significantly. Only when policymakers feel the impact of this broken system for their own families may there be reforms and funding to fix it.”

___

Copyright © [2023] Salve Regina University. Originally published by OceanStateStories.org

G Wayne Miller is an author, journalist, filmmaker, and director of Ocean State Stories, the non-profit, non-partisan news publication based at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy that is devoted to in-depth coverage of issues of importance to Rhode Islanders. Miller is also cofounder and director of the Story in the Public Square program, also based at the Pell Center. And he co-hosts and co-produces with Jim Ludes the national Telly-winning public-television and SiriusXM Radio show “Story in the Public Square.” A full-time journalist since 1978, Miller has been honored for his work more than 50 times and was a member of the Providence Journal team that was a finalist for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in Public Service. Three documentaries he wrote and co-produced have been broadcast on PBS, including “Coming Home,” about veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, nominated in 2012 for a New England Emmy and winner of a regional Edward R. Murrow Award. His 21st book, “Unfit to Print: A Modern Media Satire,” will be published on October 10, 2023. Visit Miller at www.gwaynemiller.com.

I lost my mother in June 2020. I cared for her for several years as the disease took her life in inches. I worked full time, I barely slept at night and hired caregivers to take care of her during the days. I could not do it any longer and had to find her a nursing home. I had to hire a lawyer at the cost of 10,000+ and had to spend down her life savings, paying full price for the nursing home until she had 4K left in her account finally becoming Medicaid eligible. She had a $5K life insurance policy that they counted as an asset so we were left to make a funeral home the owner of the policy so we could one day bury her. If I had supports like night time care so I could sleep and occasionally respite care, I would have gladly kept Mom at home. It would have been cheaper for the State of RI to do this for her and me than having to pay the exorbitant costs that nursing home care charges. The system is very broken and I pray someone in a position to be an advocate and be heard will take on this important need for change.

I am a caregiver to my husband who was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s and I agree that people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers are not getting the services they need and it’s even worse for the early onset patients, there is no place for them to go, I can no longer care for my husband, as it’s affecting my physical and mental health but there are no nursing homes willing to take a 63 year old who is fairly healthy, and strong and has a lot of agitation and the hospitals can only keep him for a short time to regulate the meds. And I’m told if he becomes aggressive with me that I should call the police, to me that’s absurd, does one not realize how traumatic that would be for the patient, You say there needs to be a voice for them but where does that voice come from? How do we get that voice? Our family is devastated and I have my own medical issues that continue to get worse, we are broke living off disability and my biggest fear is what will happen to him should I die before him, but for now even though I’m burnt out and feel that I’m not qualified to give him the care that he deserves I continue to be his voice because he no longer has one and Rhode Island is failing this population big time!

Thank you for sharing your experience. Now retired, I dedicated my 40 year career to working with individuals with dementia and their caregivers.

The article points out that the hospitalization was effective in controlling Richard’s dementia related behaviors. The purpose of those hospitalizations are primarily for medication “trials” usually 3 to 10 days after which a person is usually discouraged home or to a nursing care facility. Unfortunately, if a person’s illness is at a point where they can only be kept safe with heavy duty psychotropic meds, those placements fail because nursing homes are not allowed, by law, to administer those meds. Is it ideal no but you’re right, the system is broken.

It is unrealistic to expect a nursing home to be able to manage a potentially dangerous resident given today’s laws.

My statements are anecdotal but research regarding nursing home placements from a hospitalization would be telling and are a very important piece in the puzzle of Alzheimer’s care.

I don’t understand why it’s unrealistic to expect a nursing home to care for potentially dangerous patients, I would think there are patients without Alzheimer’s that have the potential to be dangerous and why are the so called secure dementia care units only accepting the frail, elderly patients who probably require less work than the younger patients? Why are the staff at these nursing homes who work in these units not being specifically trained to work with these patients? It almost seems discriminational to me. For example I don’t think a nursing home would refuse a cancer patient based on the type of cancer or the stage of disease they are in. I do not mean to offend you or anyone else and have never worked in healthcare so that is why I ask these questions thank you