Search Posts

Recent Posts

- In the news: Quick recap of the week’s news… 6.14.25 June 14, 2025

- Drowning in corruption in Bonnet Shores: Hundreds sign petition. No action by lawmakers. June 14, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 14, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 14, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Train smarter, not harder. Multi-use fitness tools – Kevin Kearns June 14, 2025

- Out & About in RI: Miriam Hospital Gala raises over $890,000 June 14, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

![preferred-Charlestown Beach[28] preferred-Charlestown Beach[28]](https://rinewstoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/preferred-Charlestown-Beach28-scaled.jpg)

Outdoors in RI – Risky cattails, Fight the Bite mosquito report, 2A gun ban bill update

Fire hazard: Phragmites sometimes pose an overlooked risk

Photo, top: Charlestown Beach, URI Photos / Laura Meyerson

URI invasives expert studies a problematic plant

Laura Meyerson was stepping through a marsh on the Housatonic River in Connecticut on a picture-perfect day as a young graduate student, when an offhand remark changed her whole outlook on the landscape in front of her.

Meyerson was observing a beautiful scenic outlook overlooking cattails. Then her professor made a comment that stopped her in her tracks. He pointed out that the scene was pretty, but that the nearby invasive reeds were going to wipe out the native muskrats. The day became a turning point in her career.

“I knew then I wanted to study this plant species,” Meyerson recalls.

Meyerson, today a professor of natural resources science at the University of Rhode Island, would like to see other New Englanders recognize the ubiquitous plant known as Phragmites australis growing by roadways and ponds for what it is.

Meyerson’s research on invasive species is global in nature, taking her to Iceland this fall. After getting her Ph.D., Meyerson worked in biosecurity for the Environmental Protection Agency and consulted with Homeland Security on pathogens that could cripple the U.S. food supply. She has served on the U.S. National Invasive Species Council Advisory Committee, is co-editor for the journal Biological Invasions, and has conducted research on invasive species at the Smithsonian Institution.

Meyerson finds many reasons to be concerned about invasive species. The fire risk posed by phragmites is just one. She says that while local fire departments are aware of the plant’s risk, those living or working near large stands of the plants may not be.

Risky reeds

Introduced phragmites (pronounced frag-mite-eez) was first detected in the U.S. in the 1800s, but it’s a historic plant dating to biblical times that grows on every continent except Antarctica.

For invasive introduced phragmites in the Northeast U.S., where the species is now widespread, this process begins in March. They don’t die back until October or even November, later than many native species. When they do, the dead stems remain standing for a couple of years, decomposing slowly and creating a dry flammable wrack layer.

“You end up with dead standing stems with highly flammable seed heads,” Meyerson says, “which float up in a fire, plus a thick flammable layer of wrack. It is quite incredible. They can catch like fire bombs.”

The stems have a high lignin and silica content, meaning they are fire-resistant to boot. Basically, they are torches waiting for a match.

“They are just ready to burn when droughts happen,” Meyerson says.

Events like the 2023 wildfires in Lahaina, Hawaii, fueled by non-native grasses and strong wind, have increased public awareness of their dangers.

But most of the time, as people see invasive species all over the place, they become a part of the landscape, often viewed as a normal part of nature — when in fact they are not. This phenomenon is known as “shifting baseline syndrome,” Meyerson says. If a plant has been here in the U.S. for hundreds of years, you assume it was always there.

Phragmites at Fenway

If Meyerson can’t stop seeing phragmites now, the same could be true for more of us.

Invasive phragmites are all over our North American landscape, dotting New England and beyond. Larkin Pond near URI has them; Block Island, too. They even took over a vacant lot next to Fenway Park, standing 20 feet tall, an unwelcome green monster.

Meyerson says there have been many efforts locally to eradicate the fast-growing plant between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. She points to a successful eradication project in Galilee led by URI’s Frank Golet, a national leader in wetland management, restoring the saltmarsh at the Point Judith causeway. Sometimes, pesticides are needed for eradication, as was the case at South Kingstown’s Moonstone Beach.

From the East Coast, phragmites have moved across the country and are now an issue in the Great Lakes, the West Coast, and the southeastern U.S., disrupting waterways in Louisiana, Texas and elsewhere. At this point, eradication may be impossible, but the species should be managed or controlled.

“It’s one of the world’s most successful plant species,” Meyerson says, to the detriment of native plants. And yes, those Connecticut muskrats, which were pushed out of their river home all those years ago.

What can Rhode Islanders do, besides advocating for support for their nearest wetlands and increasing their awareness of these invasive neighbors? Meyerson recommends buying and planting native plants.

“Check the status of the plants you buy,” she says. “It’s easy to plant native; URI’s Master Gardeners and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey have a wealth of information they can share.”

Other tips she offers:

● Manage invasive plants, like bittersweet and invasive knotweed, around your home.

● Be careful of pesticides and herbicides, which harm genetic diversity and resistance. Always read the label carefully and use them responsibly.

● Talk to your neighbors about what you see in your yard and use an app like iNaturalist to identify and report invasive species.

● If you find an invasive in your yard, pull it, double bag it in plastic, and send it to the dump; don’t toss it somewhere where it will continue to grow.

● If you plan to control phragmites on your property, be sure to get the right permit from the Coastal Resources Management Council and consult an expert. Verify that it is the invasive introduced variety and not a native plant to protect.

“Most of all, don’t give up,” Meyerson says. “Controlling invasive species can take time, but patience pays off in the end. These are little things, but they matter.”

___

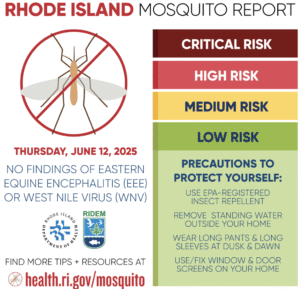

Fight the Bite this Summer – First RI Mosquito Report of 2025

As mosquito season begins, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) announce that the first mosquito samples tested by the Rhode Island State Health Laboratories (RISHL) show no signs of Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) virus, West Nile Virus (WNV), or Jamestown Canyon Virus (JCV). During mosquito season, DEM collects mosquitoes which are tested at RISHL weekly through mid-October. Announcements are made when positive findings are detected. Check RIDOH’s arboviral surveillance data webpage for updated weekly test results. For prevention tips and local data, visit health.ri.gov/mosquito. For mosquito control info, visit dem.ri.gov/mosquito.

EEE is rare in people but is a very serious virus, with a much higher mortality rate than WNV and lasting neurological effects for survivors. Unlike WNV, which is prevalent in RI every year, EEE risk varies year to year. For more information on EEE, visit www.health.ri.gov/eee.

WNV is more common and is the main mosquito-borne disease in the US. While most people with WNV don’t get sick, some develop a fever or, rarely, serious illness. About one in five people who are infected develop a fever and other symptoms. There are no vaccines to prevent or medications to treat WNV in people. For more information about WNV, visit www.health.ri.gov/wnv.

As mosquito season progresses, these virus levels rise with each generation of mosquitoes. Take the following measures to protect from mosquito bites and help minimize mosquito breeding:

Protect yourself

- Put screens on windows and doors. Fix screens that are loose or have holes.

- Avoid outdoor activities at dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active. When outside, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants and use bug spray.

- Use EPA-approved bug spray with DEET (20-30% strength), picaridin, IR3535, or oil of lemon eucalyptus or paramenthane. Follow label directions. Keep bug spray away from eyes, and wash hands after use.

- Do not use DEET on infants. Check the product label to find the concentration of DEET in a product. For children, use repellents with less than 30% DEET.

- Put mosquito netting over playpens and strollers.

Remove mosquito breeding grounds

- Remove items around your house and yard that collect standing water. Just one cup can produce hundreds of mosquitoes.

- Clean gutters and downspouts so they drain properly.

- Empty and cover things like unused pools, boats, planters, trash bins, and tires.

- Remove or treat standing water on pool covers with eco-friendly products, such as Mosquito Dunks.

- Clean and change birdbath water weekly.

Best practices for horse owners

- Vaccinate horses early in the season. Check with your vet if unsure.

- Keep animals indoors at dawn, dusk, and night when mosquitoes are active.

- Use insect-proof facilities and approved repellents frequently.

- Watch for signs like fever, stumbling, or behavior changes, and contact a vet immediately if you notice anything unusual.

___

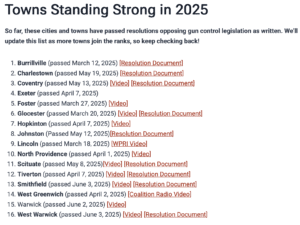

2A Update in Rhode Island

We await the fate of the assault ban bill working its way now, through the Senate, having passed the House. It is in Senate Judiciary where it can be passed to the floor for a full vote – and ultimate passage – or linger in committee and not be brought forth.

Here is an update of RI cities and towns which have taken up resolutions or statements opposed to the bill:

Senate President Lawson supports passage of the bill and notes there are 22 Senate sponsors of the bill.