Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Out & About in RI: Centreville Bank Stadium opening day for RIFC in Pawtucket May 4, 2025

- Compact Garden Accents – Christine Bunn May 4, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for May 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly May 4, 2025

- Gravity, or the Statue of Robert E. Lee Commanding Nothing. A short story – Michael Fine May 4, 2025

- Gimme’ Shelter: Tiny Bubbles here at Providence Animal Control Center May 4, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Gravity, or the Statue of Robert E. Lee Commanding Nothing. A short story – Michael Fine

Gravity, or The Statue of Robert E Lee Commanding Nothing

by Michael Fine

For Paul Stekler

© 2025 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

___

He and his horse are larger than life, a lone soldier on a smaller horse trailing him, set on a pedestal twenty feet above the ground. They sit alone, in the middle of a putting green, on a little golf resort that is supposed to look like a Texas frontier town, in Texas itself, in a little place called Lajitas, which is about fifteen miles from Big Bend National Park, on the Rio Grande, just across from Mexico, the border and the river snaking next to a road going another fifty or hundred miles west, to Presidio and Ojinaga, Mexico, in the high Chihuahuan Desert. There is nothing but mountains, cactus, dried scrub plants, and cottonwood trees — but only along the river and near the few and far between natural springs — and only a few people and pickup trucks, a few SUVs and dusty cars, and lots of brilliant sunlight, even in January.

The statue once sat in a commanding position in Dallas, on a high point looking down on Uptown and Cedar Springs, near thousands of people who would walk and run around it, in a little oasis of green in the middle of what became a big and diverse city, not that the area in which the statue stood was all that diverse. About two miles from the Texas School Book Depository, where John Fitzgerald Kennedy was shot.

The statue was erected in 1936, seventy years after the defeat of the confederacy, and dedicated on June 12, 1936 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a dedication attended by over 50,000 people and broadcast nationally, in what must have been a nod to the southern conservatives who were part of the political base of the Democratic Party, a strange collection of unlikely bedfellows if ever there was one, the “Solid South” sticking with Democrats because they weren’t Republicans, who, in the memories of those southern conservatives, were the party of Lincoln and hated by those conservatives until the Democrats became first the party of civil rights and then of diversity, equity and inclusion, ideas which those conservatives hated even more. The statue came down in 2017, auctioned by Dallas after Charlottesville blew up when that city tried to take down their own not-so-little statue of Robert E Lee.

The Dallas statue was moved to a decommissioned Naval Air Station called Hensley Field and stored there until it was auctioned online and sold for $1.435 million to the Holmes Firm PC, owned by Dallas real estate lawyer Ronald Holmes, and was given by him to the resort, which is owned by pipeline billionaire Kelsy Warren.

Robert E. Lee, followed by an unknown soldier, also on horseback, now sits in the middle of a putting green, near a driving range. The statue has a speaker at its base that plays soft rock and contemporary country music. A hundred feet away is an odd ten-foot-tall bronze pedestal clock that looks like it belongs in the middle of a city. Robert E. Lee on horseback. Near a pedestal clock. Next to a putting green. Next to a desert.

Lonely. The setting is lonely, overblown, and more than a little absurd. A meaningless lost cause, the trauma it brought a people and a nation trivialized, as we seem unable to prevent trivializing ourselves. As one or two people at a time hit golfballs. In this lost place, in a distant corner of America, in a more distant corner of the known world, a place surrounded by trailer parks for elderly retirees with no place else to go. Where, at least, the sun almost always shines. And is 120 degrees in summer.

A plaque at the base of the statue says “The lone soldier following General Lee represents the thousands who followed him into the saddest time in the history of the United States of America. May we always remember lest we forget. May we never forget lest we repeat our mistakes.”

When Celia went into the Panther Junction Visitor Center while Mark hit the men’s room, she was looking for a Diet Coke, no more, no less. Their little junket was everything she wanted it to be. Mark had flown eighteen hundred miles to be with her, and they had driven eight hours across west Texas to be here together, but Celia had what she wanted right then — Mark’s undivided attention, for once, far from anyone and everyone, and far enough away that they were unlikely to be recognized, noticed or distracted. No friends or relatives. No press. No kids or kids’ friends, or friends of friends who happened to be in town. No husbands or wives.

There was also no Diet Coke. So Celia spent a moment, drifting from display to display, walking cautiously around the green and yellow topographical map in the center of the room, and then wandering through the shelves that held books and puzzles, hats and snow globes. Hats were on sale, but the hats on sale were floppy hiker’s hats, and nothing that could be considered stylish or flattering.

A gang of people who had come to register for campsites and find out about walking trails gathered in front of the park ranger’s desk. They – Celia and Mark — weren’t camping, thank God. They were staying at the little resort in Lajitas, which was designed to look like an old Texas frontier town. So they didn’t have to sleep on the ground, thank God, and they had their privacy. They’d come up for air on Day Three and decided to do a little exploring, having exhausted themselves with explorations of a different sort.

“You might find trinkets next to the trail in different places,” the ranger, a tall and plump person of uncertain gender with long blond hair, was saying. “Little scorpions or roadrunners made from wire and beads, or walking sticks, or sombreros, or jewelry, with locked metal cannisters labeled “donations” next to them. Understand all of that is left by people who have crossed the border illegally, and who come and go without crossing at the designated border station at Boquillas. So everything you see there is contraband, and subject to immediate confiscation by the Border Patrol.”

“It sounds easy to cross the border. Is it legal?” asked a woman with dusty hiking shoes, loose khaki clothing and a hiker’s hat.

“Legal with a passport,” the park ranger said. “You cross at the Boquillas Crossing Point of Entry. After you’ve gone through Border Control. The Boquillas Port of Entry is the only port of entry in the US that is in a National Park.”

“Is there a bridge? Across the river?” a man wearing a t-shirt and beige shorts asked.

“No bridge,” the park ranger said. “There’s a rowboat that will take you across for five bucks. Or you can swim. Or wade across. The river is pretty low at this time of year. So it’s probably not even waist high and not very wide – twenty or thirty feet across, no more. But it’s cold, so most people take the boat. Then you can walk up to Boquillas village or ride up by truck or on a horse or a donkey. There are two restaurants in the village. You can eat or buy souvenirs. It’s pretty small – two or three hundred people, who live off the tourists who go over.”

“Lots of tourists?” a pear-shaped woman in a red blouse and wearing sunglasses asked. She looked like she was with the man in the t-shirt and beige shorts.

“Not many,” the park ranger said. “No more than thirty or forty a day, depending on weather and time of year. This isn’t Tijuana or Juarez. We’re in the middle of the Chihuahuan Desert. So it’s pretty quiet here. No big deal, if you ask me. But to each his own.”

“Can’t you just cross the river on your own?” the woman in the hiker’s hat said. “Like, without a passport? I don’t have a passport with me.”

“You’d be breaking the law. And you’d be in Mexico with no record and no protection. If anything went wrong, you’d have no recourse, no way to get help. There are cartels and so forth that operate here. Not many, because we’re deep in the middle of no place, with nobody nearby, not in the US and not in Mexico. But the cartels are here. They just stay quiet, and use this part of the world for smuggling, which is easy to do, because there is nobody much around.”

“But couldn’t you just go? Go over for a minute and then come right back? I heard the Rio Grande is just a little stream around here, that it shrinks way down because of climate change and people sucking away the water upstream. If there’s nobody here, who cares? You go across and you come right back. No harm, no foul.”

“Again, you’d be breaking both US and Mexican law. I can’t recommend anyone do that. Actually, I wouldn’t even think about doing that myself. It might look easy if you don’t know your way around. It’s easy to wade across the river. That’s true. But poop happens, if you pardon my French. Come back next time with a passport. Use the border crossing. Go have lunch in the village. But please please please obey the law.”

The trinkets were laid out on the rocks at the Boquillas overlook, just like the park ranger described. The trinkets on the rock were just like what the park ranger said. Locked metal cannisters, labeled “donations”. Prices next to the trinkets: a wire-and-bead roadrunner or wire-and-bead scorpion for $10, a sweater for $30, painted walking sticks for $20. Nobody there, minding the store. Or at least, no vendor, no one hustling their wares or there to collect money. You were free to walk away with what was there if you wanted. There was, however, a park ranger, in uniform, sitting in a patrol car about thirty yards away with his window open.

Celia picked up a necklace made from hand-painted beads and held it up to her neck. Mark wandered to the edge of the lookout and saw what little there was to see: a sandy beach below, abutting the narrow pale blue water, clear and almost topaz in color. A canoe and a rowboat beached in the sand. A village of thirty or forty houses on a bluff behind the beach, perhaps half a mile away. Thin columns of smoke rising from one or two of the yellow and orange adobe buildings on the bluff. Pale blue sky. Bright sun. Thin breeze.

“You break it you bought it,” the park ranger said.

“So do I get arrested for looking?”

”Not by me. The Border Patrol does the arresting. I’m just here to scare off bears and mountain lions. To protect them from marauding people.”

“No,” Celia said. “Bears and mountain lions?”

“They’re here. But they avoid people like the plague. You got to watch out for the humans around here, not the animals.”

“Really? Everything here seems so peaceful,” Celia said. “I don’t get why what’s being sold is considered contraband. People have to make a living. It’s not like that stuff is filled with cocaine or fentanyl.”

“People from the village come across the river at night illegally,” the park ranger said. They leave this stuff where you’ll see it. Then they come back across the next night to collect their donations. It’s all imported illegally and makes use of illegal border crossing. So, contraband. You can look but not touch. People fall for it anyway.”

“So people go back and forth across the border illegally?”

“All the time. The river isn’t much of a deterrent.”

“Why don’t you arrest them?” Celia said.

“Why bother? They aren’t hurting anyone. They sleep every night in Mexico, and no one here has to feed or house them. They know if they hurt anyone, we’ll close the border and the village loses its livelihood.”

Celia put the necklace back where she found it. The world seemed suddenly full of moral ambiguity. Not that moral ambiguity had ever seemed much of a problem to Celia before.

The hoofprints and horse manure on the Boquillas Canyon trail were the first indication that things were not going to be as Celia had expected.

But Celia locked her wallet in the glove compartment, pulled her hair back and held it with a scrunchie, put on a hat and sunscreen, made sure there was a bottle of water in her day pack and bounded up the trail in the bright sunshine, despite the challenge of the initial climb, which was not more than two hundred feet of elevation. Mark, still spent from their two nights of exertion, wandered more than hiked. He was famous, more or less, and out of shape. He was used to his power and prestige carrying his weight, instead of his legs. Still, he was a tall man, and neither thick nor thin, with slicked back black hair that glistened in the sun and tanned skin. Beads of sweat formed quickly on his brow, and he looked down, first at his feet as he walked, to make sure his footing was secure, and then at his cellphone, a silly gesture, because there was no cell service where they were, deep in the middle of no place. The dust and gravel were tan and almost yellow. The sky was blue and clear. The rocks and hills yellowish, pale red and gray, their color changing as the sun shifted its position, the only color on the ground coming from prickly pear cacti, some pale green, like cucumbers, and others dark purple, like sea urchins. Celia could hear the sound of rushing water in the distance and see the thicket of bright green cane growing near the river, under the cottonwood trees below them. A red-tailed hawk cawed as it floated out of the canyon, surfing the thermals, and desert sparrows skittered in the underbrush.

The man sat on his haunches next to a hobbled paint horse at the top of the hill. He was thin and bronzed, with a gray moustache. He had a red bandana tied around his neck and a blue Boston Red Sox baseball hat on his head, a baseball hat with little red and white winged feet on its front crown. The horse was white, brown and black with small patches of gray, and had brilliantly blue eyes. It stood on three of its legs, the fourth bent at the knee with the hoof off the ground, with just a few flies buzzing around its eyes and hind quarters and its eyes half closed as if it were asleep. The sun was strong, but the air was still cool and dry, cool, not cold, but warming.

Celia was breathing hard when she got to the top of the rise. There was another set of trinkets laid out on a flat rock, the same trinkets as before, along with a cooler and a hand-lettered sign. And another locked metal cannister marked ‘donations”.

“Tacos, $20. Water $5.” the sign said.

“Twenty-dollar tacos. Must be caviar or duck,” Ceila said.

“Pollo o carne” the man in front of the horse said. He didn’t stand up. He didn’t smile.

“No Diet Coke?” Celia said.

“Solo agua,” the man said

Celia didn’t touch the trinkets or open the cooler. She moved away from the flat rock to the other side of the rise. But something inside her told her to wait until Mark made it to the top, huffing and puffing, before she started back on the trail as it descended back to the riverside.

Even with Mark just a few yards behind, the canyon was a lonely place. Maybe it was the sheer gray and white limestone walls, which towered 1500 feet above them and shut out any sense of the outside world. Maybe it was the quiet: no sound of distant trucks, rumbling on a highway in the distance; no jets flying overhead, no radios or cellphones ringing. Just the sound of river birds, rustling in the thickets and chirping from time to time; just the gurgling of flowing water from the river’s edge; and just the hiss of a soft breeze blowing out of the canyon through the reeds and grasses.

There were no people on the path, and no signs of civilization. A few footprints. A few hoofprints. But no voices. The canyon walls cast a shadow on the path and the thin strip of ground between the walls and the river. The sun came into the canyon as a sliver of light, falling mostly on the river, surrounded by darkness and shadow. In the canyon, nature overwhelmed human scale. Celia felt puny, insignificant and alone. There was no horizon to look at. Just sheer rock walls.

Celia let Mark catch her. She wanted him to wrap his arms around her and pull her close to him. You can’t walk that way on the path they were on. But you can stand there for a few minutes, wrapped together and plugged in, warming one another.

But Mark was off somewhere in his own mind. He let Celia put her hand in his hand as they walked. He let her pull his arm around her shoulder. But that arm was a dead weight, with no strength or passion behind it. And he shuffled, instead of bounding ahead, a pace that was too slow for Celia, who was feeling her legs and the strength in her back and was ready to push herself, to see what she could do. She was ready to challenge herself and wanted to challenge Mark as well, to see what they had in them, to see just how much there was here, to go further and faster and better, to see if they could really live at the edge together, to see if being together made life more than it had ever been before.

“See you where the trail ends,” Celia said. She wriggled away and started walking faster, with a long stride, swinging her arms. She looked back only once to see if Mark was up for the challenge and was trying to catch her. He wasn’t.

The trail ended a few hundred yards upriver. It sputtered out on a sandbar, a wide place in the river where the water was only an inch or two deep. The river water flowed between tiny rock islands and spits of sand and gravel, although there was a place on the far bank where the current of blue water ran fast and deeper, fast blue water that glistened in a sliver of bright sunlight. You could walk upriver on that sandbar, walking on the rocks and islets, so Celia walked, uncertain Mark would follow.

The river and the canyon walls turned to the left. If Mark didn’t follow, he might not be able to see her from where he stopped, but in that moment Celia didn’t care. Walking on her own, stretching her legs, learning what she could do, listening to the birds and the river sound, being in that glorious air where there were no cellphones or telephone wires or soda cans, no trucks or airplanes or rules – that was where Celia wanted to be and how Celia wanted to live. Unencumbered. Unjudged. Going where normal people didn’t go. Doing what normal people were too afraid to do.

A tree. There was a tree that must have fallen from one of the canyon’s walls, a tree that had been carried downriver by the current and was stuck in front of Celia, where the river widened, just at the mouth of the fast channel. The branches, which still had leaves on them, had come to rest in the shallows where Celia was walking. The roots were stuck on the far bank, which was no more than ten feet away. The trunk and some of the branches bobbed up and down with the current, which backed up behind it and then flowed over parts from time to time.

Huh, thought Celia. I wonder.

The far bank, so-called, was so close Celia could almost touch it. There were gray and black speckled rocks and twisting brown and tan roots at the water’s edge. Brush with a tangle of branches and tiny lime green leaves and some small white flowers. There was a foot path just behind the brush, compacted tan earth with footprints that Celia could see from where she was, and perhaps fifteen or twenty yards of rockfall, gravel and dirt before you got to the far wall of the canyon, which towered over her, a fierce, unforgiving gray shale that rose thousands of feet over Celia and over the river, a ponderous monstrosity that was too steep to climb. Clusters of branches and twigs hundreds of feet up. A nest. Maybe an eagle or an osprey.

But that’s Mexico, Celia thought. Forbidden.

Still, I think I can walk on that tree trunk. It’s big enough. It will hold me.

Mexico.

Illegally.

Scary. Just a little. But that side looks just like this side.

How cool. I can do that. I can go over, walk further into the canyon on that path, take a couple of pictures with my phone and then come back. Who will know? Mark won’t even know.

But you’d be breaking the law, another voice in Celia’s head said.

What law? The first voice answered back. No people, no law. If a tree falls in a forest and nobody hears it. No harm, no foul. I don’t know where the international boundary is. I’m more than halfway across now, in the shallows. I’m probably in Mexico already.

I don’t know, the second voice said.

But by that time, Celia was standing on the tree trunk, trying to keep her balance as the trunk rose and fell with the current. One step at a time, Celia told herself. Like a tightrope walker. I can do this.

She focused and spread her arms for balance. One step at a time. Daring young Celia, on the flying trapeze, who was not as young as she used to be.

She fell, of course. She slipped and fell and ended up in the river.

She was more than halfway across but halfway was just a few feet and was so close she could almost touch the far bank. The bark of the tree was wet, and it was slippery, so when the tree bobbed in the water, Celia lost her balance and slipped forward waving her arms as she fell. “Ohhh!” she yelled, as she fell. Not a yell for help. Just a yelp of surprise.

She fell forward and hit her bum on the log as she came down.

Big splash. She landed on her knees, in the river, with the cold blue water flowing fast around her. The current was strong but not overwhelming, so she tumbled to her feet, the current pushing her downriver as she stood, and spinning her around a little, until she grabbed at the roots and branches on the far bank she had been looking at a moment before, and held onto them, using them to pull herself out of the current, and then like a climbing rope or a banister, using them to pull herself up onto the bank.

Soaked. She was soaked. Celia stood in the bright sunshine and shook herself off, the way a dog would, laughing at herself as she did so. Daring young Celia on the flying trapeze. Not so much. There was water in her shoes and down her back. Her fleece was soaked. There was water on her glasses and her hair was wet.

She let her hair out of its scrunchie so it would dry. She checked her pockets and day pack. Her cellphone was still in her back pocket, but Lord only knew if it was still alive, or could ever be brought back to life, not that it was any good, where she was at the moment. No reception. So much for pictures of Mexico.

You worry about hypothermia, of course. Where the hell was Mark? She could yell for him, if she could see him, not that he was going to be any good to her, right at the moment; not that she wasn’t a little ashamed for going out on a limb, literally, and then falling in the drink. But in a part of her brain, she hoped he had seen her fall and then hoped he would come over to this bank, would help her wring out her wet clothing and set it to dry on the rocks and bushes, and then hold her to keep her warm while she dried off. They could even make a fire to stay warm. Pretty romantic, when you got right down to it. But another part of her brain wanted all this to go away, wanted to sneak back across the river and pretend that she hadn’t tried to cross and hadn’t fallen in the river. Too late for that, though.

She took her shoes off and poured out the water in them. She sat on a rock and took off her socks, rung them out, and hung them over a branch. Then she shimmied out of her fleece and wrung it out as well and then laid it on a rock. Let me stay in the sunlight, she thought. It’s dry here. Maybe I’ll dry a little. But she shivered in the cool wind, despite the sunshine.

She walked forward on the path a few steps, looking at the other bank, for Mark, looking at America. Both banks were the same – little flat places next to a river, at the bottom of a canyon made from towering unforgiving rock walls. Overwhelming. Lonely, she thought. I’m trivial. Meaningless.

That was when she heard a sound, a whistle behind her, a loud high-pitched blast that reminded her of a train whistle or the sound kids on a playground make by putting two fingers in their mouths, to call to one another across a street or down a city block. Huh, Celia thought. There’s no one else here. Could that be Mark? calling from across the river? when he realized he was at the point on the other side where the path ended in the shallow flat place? whistling when he didn’t see Celia? But no. The loud whistle came from behind her, on her side of the river, from the cottonwoods and tall cane.

A woman came around a bend in the path thirty paces in front of Celia

The woman was thin and bronzed, with black eyes and black, white-streaked hair, held loosely behind her head in a rubber-band. She wore a bright red checked shirt and black jeans held up by a silver-and-turquoise studded black belt that had a bright silver buckle. There was a silver stud in each of her pierced ears and she had a silver nose ring in one nostril.

“¡ Buenos día! ¿Cóme estás?” the woman said.

“Wet,” Celia said. “I fell in the river. I’m cold.”

“Y estupida,” the woman said. “¿Ustedes people, una countria no es sufficiente para you?”

“I’m wet and I’m cold. Spare me the lecture,” Celia said, her teeth now chattering and her lips blue.

“Take clothes off. We build fire. So not to die.” the woman said.

Celia took off her wet shirt and pants, thinking that what she needed, right at that second, was a blanket to wrap herself in. She was cold, Celia thought later. You don’t think straight when you are getting hypothermic. Not that she had many options, standing there. Just in her underwear. In a foreign country. Without a passport.

It’s not a problem, Celia thought. Another woman. No one else around. Bright sunshine. What could happen?

The woman put two fingers in her mouth and whistled. Celia half expected to see a horse trot up by itself. Remember Trigger?

Three ruddy men with bad haircuts appeared on the path from where Celia had come out of the river. They were carrying her fleece and her shoes.

Celia understood she was in over her head. But they had a blanket. And looked like they might be ready to deal.

Mark didn’t know what to make of things when he got to the end of the path and didn’t see Celia. His passion spent, Mark was finessing as usual, trying to find a way to fit the pieces together so he came out in control, where he wanted to be, holding all the cards. You stretch here and you snip there. Let someone believe you are with them here, be cagey there. You stay cagey. Keep your cards close to your chest, because that way you always have leverage, that way you can usually get someone to do what you want them to do, even if that something is not in their interest. There’s a little larceny in all of us. You just have to sniff out who is overstretched and how, and hint you know that. Who is embarrassed or embarrassable. Who wants what. Then you play the cards you have, not the cards you want, but you make sure you are the dealer – and the house always wins.

The path ended in the river. There was no place else to go. They were in a canyon. The canyon walls were huge and sheer. All rock. Where did that damn woman go?

She always wanted more, that woman. Most women do. More time. More attention. More flattery. But she was hot. Red hot. And unquenchable. Mark deserved what she had to offer. He had put in his time. Paid his dues. Now it was his time to take some profits, to enjoy the spoils of battle, to bask in the sunlight a little. And that woman knew how to bask. And more.

But where the hell was she? He stood still for a few minutes, expecting her to jump out from behind a tree or a rock. Maybe naked. Worse things have happened.

The river was wide there. And shallow. Sunlight bounced and danced as it was reflected from the shallow water, the surface pockmarked by rocks and little islands of gravel, the water trickling downstream between the rocks. The current ran swift only at the far bank, where the water was blue. Mexico, over there, Mark thought. Uncharted territory. Bad things happen there. A different universe. With different rules. And nobody he knew. So no leverage.

He heard someone whistle.

Maybe she had slipped by him by walking on the riverbank as he was walking on the path. Some kind of game. Maybe looking for a little leverage of her own. She wouldn’t be the first.

So Mark kicked a few rocks by the riverside, shrugged his shoulders and turned back to the path. They’d meet up at the rental car. Who knows what a woman like Celia was up to anyway. Which was part of the attraction, when you got right down to it.

Then he heard a second whistle, just downstream from him and on the other side of the river. He saw the movement of people there. He ducked behind a tree.

A hawk dove from a ledge above him, brilliant brown and red in the blue sky and sun. It missed the sparrow it was after, and swooped upward again, beating its wings slowly three or four times, a slow cadence, working hard at first, until it caught a thermal, which carried it into the air high above.

Celia saw the hawk and then saw Mark walking away.

They had brought her upriver, near the place where the river widened and the path on the American side ended. They walked three abreast, the woman leading, followed by Celia who was wrapped in a blanket and who walked next to two of the men, who spoke to one another in Spanish as they walked, with the third man following a few yards behind them. The men on either side of her didn’t hold Celia’s arms. They didn’t need to.

A number of scenarios raced through Celia’s mind. They are going to rape and kill me. They are going to strip me naked and take pictures of me which they will sell on the internet. They are the Mexican police or are taking me to the Mexican border police and are going to turn me over to the Mexican ICE, if such a thing exists. They are going to hold me for ransom in a cave or in a hovel someplace back in the village. They are sex traffickers and are going to sell me into slavery, to someplace in Central America or Africa or the Middle East. She realized they didn’t know what she knew, that she was in Mexico without a passport, but they would find that out as soon as they searched her things, though it wasn’t clear that having a passport mattered or not.

Don’t just stand there, do something, Celia thought, when she saw Mark.

But then she realized what she already knew. Mark was a taker, not a doer. He was a man with no courage, just a guy who played the odds, who changed and twisted the truth to get what he wanted. Any leverage that Celia got when he flew eighteen hundred miles to be with her just went out the window, now that she was in Mexico and in trouble. He wasn’t the sort of man who was about to risk his life for her or for anyone else. You pays your money, you takes your chances. She got what she’d paid for. That and nothing else. You broke it, you bought it. She had broken it. This mess was hers and hers alone.

A woman in front of her. A man on each side of her and one behind. The river on one side. Fifteen hundred feet of massive rock canyon wall on the other. Very literally between a rock and a hard place, with a little river in between.

They walked forward. It was maybe a mile before they’d leave the canyon to follow the river west and south, toward the village. The US of A was no more than fifty yards away, across the river, as much good as that was to Celia now. Her country, which she never thought about, was only good to her when she was in it. Alone, she was just one person, at the mercy of anyone else who was bigger or stronger or more organized. I’ve taken my country for granted, she thought. I’ve taken for granted the laws and the Border Patrol and the Park Service and the guys who pick up the garbage and the people who build the roads and the people who stand behind the counter in the stores.

Too late now.

That bastard. That good-for-nothing, lazy, self-serving bastard, she thought, as she watched Mark scamper uphill at a place where the path on the US side turned toward the rock face and snaked around a rockfall. Climb like a mountain goat. He was dead on his feet when we were walking together. Now he suddenly finds his inner mountain goat?

He’s worried about getting caught, that creep. About there being a tussle or a fracas of some sort, a tiny little international incident, and then the newspapers that are left back home and the bloggers and the creeps will start asking questions about what he was doing here and who he was with. He’s worried about Saturday Night Live, and the smartass cracks about him walking the Appalachian trail like that other guy, human beings, me included, never once learning from the past. What were we thinking? What was I thinking?

I should just go with these people, Celia thought. Let them take me where-ever. Let the FBI or the CIA or the state cops, whoever gets called in when my brother or my kid files a missing person report, let them follow my trail here and follow it back to Mark. We were careful but we weren’t crazy. Let him get what he deserves. That that goes around, comes around.

The path narrowed and wove through gray-flecked white and tan limestone rocks that had fallen from the cliffs, rocks with flat faces, rocks the size of cars and trucks.

The woman dropped back and walked next to Celia for a few steps. Then she walked in front again as the men next to her dropped back and walked single file. A mule deer grazing at the river’s edge beneath them moved into the shadows as they approached. A lone cow lowed from outside the canyon on the American side.

Then they descended, back to the river edge. One of the hawks floating above them over the river dove again, just past the place the canyon ended and the river turned west and south –and this time came up with a fish in its talons.

“Look,” Celia shouted, and pointed at the diving hawk, and the woman and three men looked to the west.

Celia dropped the blanket and darted into the underbrush in just her bra and panties. What the hell. Live free or die. She dove into the cold blue river, the woman with black-and-white-streaked hair and the three ruddy black-haired men right behind her.

But the Mexicans stopped at the river’s edge.

Three strokes, and Celia was across the river. The hell with Mark. Celia was a woman who could take care of herself.

Then suddenly, hoofbeats.

As Celia stood up and came out of the river in her underwear, the paint horse came charging into the river, as it’s rider, the Mexican guy with the gray moustache, red bandana, and Boston Red Sox baseball cap, whooped, and then leaned over and caught Celia under the arms, boosting her onto the horse behind him. Then he spun the horse around and spurred it, so the horse cantered away, leaving the four people on the Mexican side on the river’s edge, shaking their heads with disgust.

The horse with its now two riders bounded up the trail, up the little rise toward the parking lot, and Celia, sitting with her arms around the Mexican, suddenly started to feel the warmth of the man’s back and the stringy power of his lean body, and she thought, now isn’t this something, and started to warm up to the idea of a knight in shining armor on a white horse. Same idea, different time and place, but still a man, and a good deal better than the man she had come with.

Mark was standing at the top of the rise, next to the rock where the trinkets – the red, blue, and green wire-and-bead roadrunners and scorpions, the necklaces, the sweaters and the brightly painted walking sticks – were laid out, next to the cooler with the hand lettered sign that said “Tacos, $20. Water $5” and the locked cannister marked ‘donations’ leaning against the rock.

“Looks like you forgot to dress for dinner,” Mark said.

“Fuck you,” Celia said.

The Mexican pulled his foot out of the stirrup nearest Mark and pushed that stirrup back toward Celia as he twisted his torso to his right, nudging Celia, who understood, slipped her foot into the stirrup, put her weight on it and dismounted as Mark came over to catch her.

“No bad weather. Only inadequate clothing,” Mark said.

“Fuck you twice. Where the hell did you go?” Celia said.

“I went to get help,” Mark said. He turned, pulled one of the sweaters off the rock and held it out to Celia, who put it on.

The man on the horse swung down from the saddle and knelt down next to the horse to hobble it. Then he pulled an armload of hay out of a black plastic bag and threw it on the ground for the horse to eat, and patted the horse on the neck.

Celia spun around and walked down the path, which went downhill to the parking lot, walking carefully because she had no shoes now.

Mark pulled out his wallet and handed the man with the horse a wad of cash – everything he had on him.

“Adios amigo,” he said. “Muchas gracias.”

“De nada,” the man replied, dropping his head and eyeing Mark with complete disrespect, as he got back on his haunches to wait for the next little group of tourists to come to hike the canyon, since it wasn’t even yet mid-afternoon. They come like that, in drips and drabs, all day until the sun goes down. Some buy things from him. Some do not.

Then Mark followed Celia to the car, unlocking the car with a key fob remote as he walked so the car would be open when Celia got there. See, Mark said to himself. I’m a considerate guy.

Celia was sitting in the passenger seat, her knees drawn up to her chest, shivering, when Mark got to the car and got in the driver’s seat.

“Al least that guy with the horse did something. You just stood there and watched. Who knows what would have happened if I hadn’t made a break for it.”

“So you’re a hero. And I’m a complete cad,” Mark said. He started the car and turned up the heat.

“That guy on the horse. There’s a man. Someone who knew how to stand up when it counts.”

Mark shook his head. The engine was now warm, so he turned on the blower.

“He didn’t come after you by accident,” Mark said.

He patted his back pocket. Then he threw the rental car into reverse.

“No?” Celia said.

“You get what you pay for,” Mark said. He pulled the car out of the parking lot and headed back to their hotel, the one with the weird statue of Robert E. Lee.

“You hit that nail on the head,” Celia said, feeling suddenly nauseated.

“The golden rule. He who has the gold makes the rules,” Mark said.

Celia turned her head away and looked out the passenger side window. She did not want to turn it back.

She did not want to look at or think about Mark ever again.

Suddenly Celia realized with disgust who she herself had become.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

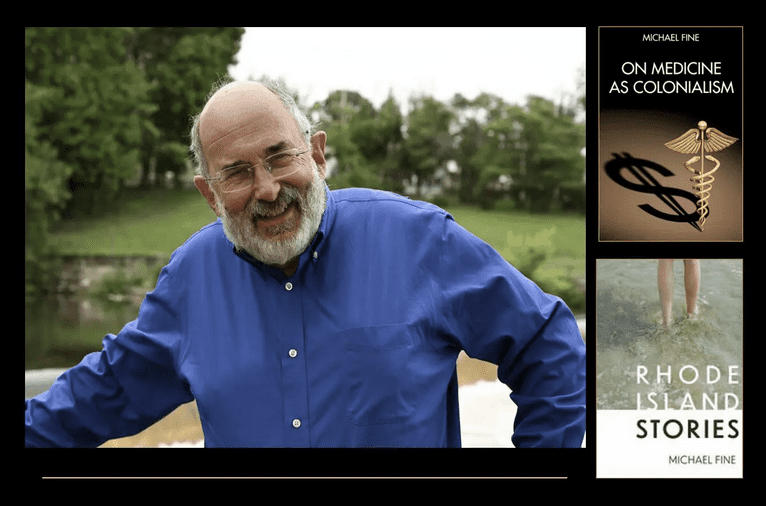

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.