Search Posts

Recent Posts

- GriefSpeak: Waiting for Dad – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 13, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 13, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 13, 2025

- Urgent call by Rhode Island Blood Center for Type O- and B- blood June 13, 2025

- Real Estate in RI: Ready, Set, Own. Pathway to Homeownership workshop June 13, 2025

- Outdoors in RI – Risky cattails, Fight the Bite mosquito report, 2A gun ban bill update June 13, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Dread – a short story by Michael Fine

by Michael Fine, contributing writer

©2025 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

It started with the landline, ringing in the middle of the night. Ten rings. Maybe more. Suzanna thought she was dreaming. Maybe she was. She stumbled out of bed. But the ringing stopped by the time she got to the phone. It was 5:37 in the morning and still dark. Late fall. No hint of dawn. The election had come and gone. She was tumbling around in the dark. They all were.

Everyone Suzanna knew was frightened. Or depressed. People sleeping late, or not at all. Getting high. Drinking alone. Crawling into bed with strangers, hoping to warm their aching souls. Running three times a day. Looking at Canada. Figuring out if they had a grandparent from Ireland. Or Portugal. Or even Germany. Anything that would get them an EU passport.

The depth of the despair was palpable. This wasn’t the result of an election where one party won and one party lost. This was a moment when the sky had fallen, when the bottom had dropped out of humanity, when history itself was repeating itself, as human beings had failed once again to learn from our past. Germany after Kristallnacht. Poland on August 31, 1939. Kiev on February 23, 2022. The hurricane was coming. There appeared to be nothing anyone could do to stop it.

The perception of impending doom. That’s what medicine calls it. It is a well-known symptom, one Suzanna and her colleagues never discounted. The sense a person has that something terrible is about to happen, that they are about to collapse and die. Doctors have recognized this description for hundreds of years because it is sometimes, and perhaps often, a harbinger of an actual catastrophic event, of a very bad outcome. People seem to know, sometimes, that they are about to die.

Death was scary. But this was worse. It was the sense that civilization and human decency were both about to collapse. Suzanna’s doctor-self always listened when a patient said they had a sense of impending doom. But what do you do when you have that feeling about the whole planet and its entire human architecture?

Suzanna fell back to sleep. Then she heard the telephone again. She jumped out of bed this time. But again it stopped ringing by the time she reached it. Was the ring real? Or had she drifted back to sleep and was dreaming?

A door blew open in the wind.

Carlos liked to jerk people around. It wasn’t meanness. He wasn’t a mean guy. He didn’t abuse the girlfriend or his kids. He was nice to them. Nice to his buddies, but a terror on the ballcourt, where he played for keeps. He showed up for weddings and funerals, and sometimes even brought the girlfriend flowers, when he was in the mood.

But people need to understand that there are rules, and the world doesn’t turn around them. Too many people have an attitude – that what they want matters, whenever they want it. They have issues. They expect everyone else to deal with their issues, to jump when they say jump, to twist and turn when they mess up their own lives.

Your failure to plan is never an emergency for me. That was the sign that Carlos hung behind him on the wall.

The sign on the door, the message on the answering machine and the information on the website all said the same thing: arrive by 3 pm for same day service. We accept credit cards or cashier’s checks. No cash, no Venmo, no personal checks.

Still they show up when they want to show up. Bring what they want to bring. Despite the rules.

And those guys who don’t speak English, they are the worst. They think the world owes them a living. They think they are doing us a favor living here, that we need to bend over backward for them, not the other way around. Like we should learn all the languages they speak so they don’t have to learn English. Like Google Translate is as good as talking. Which it isn’t. Not even close.

So all the people who showed up after 3 got told to come back tomorrow. Carlos wasn’t going to stay late for anyone. No exceptions. It takes time to process the paperwork required to get a car or truck released from impound. Credit card or cashier’s check. No cash. The sign was clear, assuming you could read and understand English. No cash, no Venmo, no personal checks. And no exceptions. Carlos wasn’t the one who parked in front of the fire hydrant. Or parked in a handicapped space. Or forgot to put money in the meter. Or who didn’t have any change, and it was an emergency because my mother-in-law was sick. Or I had to go to my kids’ parent teacher night. Or, get this, I was driving my boyfriend’s car and meeting this guy, and my boyfriend doesn’t keep quarters in the ashtray like I do because he keeps his stash there.

They all had excuses. He had heard them all.

Rules are rules.

Didn’t matter if you drove overnight from Northern Maine to get here. Didn’t matter if you are the second cousin of the Queen of England. Or were Buddy Cianci’s best friend. Or if you know a guy. Nothing matters. You show up before 3 pm with a credit card or a cashier’s check for the full and exact amount and you get your car back. Maybe. If we can find it. I don’t want to hear any bs about the scratch on the bumper or the kid’s toy that was in the back seat and now can’t be found. Or the tennis bracelet you bought for the girlfriend that was wrapped and in the glove compartment. Carlos had heard it all. There’s a form you can file if you have a complaint. A credit card or a cashier’s check for the exact amount. Anything else is your problem. You left your car in the wrong place. Or didn’t feed the meter. Don’t like the ticket you got? Go argue with a judge. At 8:30 in the morning. In six weeks. On a Tuesday. Take it or leave it. Not my problem.

So when Suzanna left the theater one Thursday night in November and couldn’t find her car, her first thought was that she had forgotten where she parked it. It was her fault. She never had her head on straight. Everything that can go wrong will. And does, every waking moment of the day. I thought I parked it on Empire Street, she thought. Up near Weybosset. Where you can sometimes find a place. But maybe I parked it around the corner, on Broad or on Greene Street. Where you can sometimes find a place there when everything else is taken.

So she walked around the corner, looking but also remembering. I’m sure I parked it on Empire, she told herself. I was looking at the sign in front of PPAC as I parked. All those bright lights. For A Christmas Carol and Hamilton. So where could my car be? Suzanna was a person who lost her cellphone three times a day and could never find her keys, so a feeling of desolation, of failure, of endless distraction and confusion never left her. What am I good for? she wondered. Can I never get anything straight? And if I can’t even remember where I put my car, how is this nation and this world ever going to get straightened out?

She walked around the block twice before admitting to herself that her car was gone. What was the world coming to? Who except Suzanna would ever want a banged up 2006 Toyota Camry?

But if it wasn’t where she left it, it must have been stolen. Just my luck, she thought. When I have to drive to New Haven in the morning. She was overcome again by the sense of falling into the abyss, of slipping into a vortex, a black hole, a death spiral. Everything that can go wrong does. Because of me, she thought.

The car was gone. So she called the police.

The woman had no idea where she was or who she was talking to. She was like all the others, only worse. The guys from Central Falls or Woonsocket who don’t speak any English or at least act like they don’t. Carlos knew exactly how to deal with that kind. They didn’t ruffle his feathers at all. No hablo Espanol. A blank stare. Then, ‘next!”

But this woman with the fancy clothes, the funny accent, the big words, the talking to herself and then her tears, it was not what Carlos needed at 3:30 in the afternoon when they were going to close in thirty minutes.

These people. They think they own the world. They think the world turns around them.

Nothing the woman said or did was going to change his mind. Rules are rules. Push me, and I’ll push back. Slow walking is slow walking. I’m not a mean guy. Far be it from me to get in the way of some poor rich woman’s suffering. You don’t pull that shit with me, Carlos told himself. Don’t you tread on me. Semper Fi. Nobody matters but number one. You take care of your own self first.

The man had no emotions. No imagination. No thought process that Suzanna could access or understand. Not even any facial expression. He sat immobile in his chair behind the plate glass window with a little cut-out in the bottom for documents. A stone pillar, a block of human marble. Not listening. Not caring.

“Not today,” he said. He spoke into a microphone. His words came out of a tiny speaker on Suzanna’s side of the glass, their sound distorted by the crackle and hiss of the electronics.

This is exactly what’s wrong with democracy, Suzanna thought. It’s made up of people like this, people who care only about themselves. What I dread about coming to places like this. And having to stand in line.

“I have done this to myself,” Suzanna said.

“Yup,” the man said. “Tough luck.”

“I have no one to blame but myself,” Suzanna said.

“You can blame whoever you want. Nobody’s listening,” the man said.

“Whomever,” Suzanna said.

“Not,” the man said. “Whoever. Whomever. Nobody cares but you. And I doubt you care that much either.”

“I just need my car,” Suzanna said.

“Next,” Carlos said without looking up, his voice hissing though the tiny speaker.

The room began to spin. Suzanna closed her eyes. She stumbled forward and put both her hands on the plate glass window for support.

“Just back off, lady,” Carlos said. “Take you hands off the glass and take one giant step backwards.”

“I’m a doctor,” Suzanna said.

“And I’m the pope,” Carlos said. “Step back from my window. Other people are waiting.”

Suzanna stepped to the side. There was no one behind her. She turned. But she didn’t move away.

The building was big, open and drafty, with stairs and signs pointing this way and that. The air tasted floral and fake at the same time – a deodorant, covering the dank undercurrent odor of human sweat and hormones.

What to do? There was no moving the man behind the glass window. Suzanna was alone. Defenseless. Without options. Without hope. Suddenly Suzanna felt all humanity itself was lost. Humanity itself, a world of people who learned from and took care of one another, suddenly seemed like a quaint idea, an idea from another time, a fading image, as if Suzanna was on a ship that had left the harbor and was looking back on mountains and a seaside town that was shrouded in mist.

But there were throngs of people clustered around, some sitting in chairs, looking at signboards with bright red numbers on them that flashed and pinged from time to time, like slot machines in a casino. Others stood at different desks with plate-glass windows like the one Suzanna was standing at, cattle lined up to come into a barn before the evening feed. There were guards in uniforms who carried guns, and lots of people who came in and out. There were windows high on many of the walls, but not much to see except acres of parking lots filled with cars. The sky was slate gray. The sun was setting. It would soon be dark.

A cold rain began to fall.

Suddenly, Suzanna saw movement out of the corner of her eye.

A security guard moved fast behind her.

A knot of people gathered around a set of chairs where the guard was headed. An overhead alarm sounded, a buzzing clang, a repeated electric shock noise like the warning beep trucks make as they back up, only louder. Much louder.

Suzanna turned. The doctor in her switched on, as if the turbocharger of a fast car suddenly engaged, or a spaceship went into hyperdrive.

The old woman was dressed in black. Her skin was waxy and white, almost blue. She wasn’t breathing. She was in a chair, slumped over, her head angled back and to the side.

Another woman, younger, wearing a black headscarf and a dark green coat, her hands spread apart, screamed “Help her, Help her, Help her.” A swarthy bald-headed man in a black leather jacket waved in the security guard as he pushed other people away.

Suzanna elbowed the man in the black leather jacket out of the way. She pushed past the security guard and felt the woman’s wrist and then neck for a pulse.

Suzanna shook the woman by the shoulders. She dropped her ear to the woman’s mouth.

“Are you alright? Are you alright?” Suzanna shouted.

The woman’s head bounced from left to right, loose, like cooked spaghetti.

“No pulse. Start CPR” Suzanna said, half-shouting but almost to herself. “Call 911. You and you, help me lay her down on the floor.” She said to the guard and the man in the black leather jacket. “Do you know CPR?”

The security guard shook his head as he lifted the woman’s legs. “You, call 911,” Suzanna shouted to the man in the booth she’d been standing before a few moments ago.

The man in the black leather jacket took one arm and Suzanna took the other. They lowered the woman to the ground.

Suzanna knelt next to the woman’s body, locked her arms, put her palms together and laid those palms in the middle of the woman’s chest. and pressed hard on the woman’s chest, sinking it a few inches. Then she released the pressure and the woman’s chest rose. Suzanna leaned back a bit, and then pressed down hard again, making a kind of piston with her arms, leaned back again, and then pressed down hard once more. She repeated that motion, rocking forward and back, forward and back, as she counted to thirty.

Then she pivoted. She leaned over the woman’s face and put her hands under it, tilted the woman’s head back, and pushed up on the woman’s jaw. Her lips touched and sealed the woman’s lips. She blew hard into the woman’s mouth, hard enough to make the woman’s chest rise. When that chest fell Suzanna blew hard into the woman’s chest again, and then, as soon as the chest rose one more time, Suzanna pivoted and went back to pushing on the woman’s chest –- thirty compressions, then two breaths, back and forth, back and forth, the icy feeling of the woman’s lips, which tasted like lime juice, on Suzanna’s own lips and tongue and the strangely warm release of the woman’s breath in Suzanna nose and mouth as the woman’s chest and muscles forced air back out of her lungs between each of Suzanna’s rescue breaths. Yes, she should have waited for a mask and not put her own lips on the woman’s mouth, there being a hundred thousand infectious diseases that Suzanna could have contracted this way. But you don’t stop to think or calculate the odds or take a medical history when someone is dying in front of you. You act. You move. You do what needs to be done, and ask all those questions later, if at all.

When she compressed the woman’s chest, Suzanna felt the woman’s ribs break, as often happens when old people get chest compressions, their ribs slender, like dry twigs that break when you walk on them. Suzanna kept her arms ramrod straight and her elbows locked. Her chest thrusts were perfect, two to three inches of compression, the result of years of drills and of teaching others, compressing and moving a little blood with each thrust, imitating, in some small way, the action of the heart’s contraction, hoping against hope that enough oxygen would get into that blood with each breath, that enough blood would move out of her heart, and that enough blood would move to the brain with each compression to preserve life, by a margin that was unimaginably tiny, the preservation of life unlikely but impossible without this action, hope being better than inaction and despair.

Two breaths. Then thirty compressions. Two breaths, then thirty compressions again, Suzanna on her knees for the compressions, then bent over the woman like a lover. Two breaths, then thirty compressions again. Oxygen, Suzanna’s brain called out. We need oxygen and a mask. And I need someone to come out of the crowd and offer to help. My arms are getting tired and I can’t keep doing this forever.

But the crowd just stood and watched. The security guard stood there with his arms spread wide apart, saying “stay back, stay back”; the woman with the black headdress keening, her face in her hands; the bald-headed man in the black leather coat on his knees, across from Suzanna, his hands outstretched, palms up, as if he was praying and mourning at the same time; the asshole from behind the glass window just standing at the edge of the crowd. He shook his head and looked at his watch, as if all these people were making a mess of his well-ordered life.

But the woman never got a pulse back. She never took a breath on her own.

EMS came. They shoved Suzanna out of the way. They brought in oxygen, a bag-valve-mask and an automated chest compression machine. They got all that going. Then they threw the woman on a gurney and dashed away, a classic scoop and run.

The woman in the black shawl and the swarthy bald man in the black leather coat vanished, running out after the EMTs.

When it was over, the woman in black was probably no less dead than she was before Suzanna got involved.

The crowd dispersed. All that was left was the usual post-resuscitation mess – wrappers from needles and tubes, odd items of clothing that had been left behind, some bottles and cans that the crowd had abandoned, and little red and blue needle covers scattered on the floor, which looked like festival grounds the morning after a rock concert.

Carlos stood on the edge of the mess, his arms crossed, still shaking his head, as Suzanna clamored to her feet. He looked down at her as she used a chair to help her stand, but he didn’t offer to help. Then he looked at his watch.

Soon it would be time for the building to close. Carlos had called 911 but he knew that the woman on the floor was already dead, that all these people were just wasting their time and his time. Tough luck. Your failure to plan is never an emergency for me. At least he’d earn a little overtime.

“You see?” Suzanna said, as she stood up.

“See what?” Carlos said. “I see a mess. Much ado over nothing.”

Suzanna shook her head. There was just no moving this guy.

“So do I get my car back?” Suzanna said.

“You can get your car back tomorrow. Maybe. If you show up on time. Before 3 pm with a credit card or a cashier’s check for the full and exact amount. Assuming you can prove you are the owner of the car and the car is in the impound lot. Get here at nine in the morning. Before the line forms. Because I shut the window at 3:30, regardless.”

There it was. The banal and the real. Who we really are. How the whole is the sum of parts, and part of us are the people who don’t think for themselves, people who care only for themselves and the rules they hide behind.

“Call you a cab?” Carlos said.

“I’ll Uber,” Suzanna said.

She walked down the stairs and out into the parking lot.

It was dark by then. There was a thin blue arc of residual light on the western horizon, marking the place the sun had been before it disappeared. The temperature was dropping. The rain had become mixed with snow and sleet. There was nothing to hope for now. Nothing to believe in.

I’ll be back, Suzanna told herself. I’ll be here at 8:30 sharp, credit card in hand.

The feeling of impending doom does not always mean an impending heart attack or stroke, she thought. Sometimes it’s just anxiety.

But Kristallnacht happened. So did the Holocaust, Rwanda, Syria, Ukraine and Gaza and a hundred thousand other pogroms and genocides. Dictators and emperors. Police states. Secret police.

Those things haven’t happened here, at least not yet, Suzanna thought. We don’t have a dictatorship. Yet.

History is line, not a circle, she thought. Each day is different from every day before it. But that doesn’t mean human beings have changed, have learned one thing, or aren’t likely to repeat our many past mistakes.

We are still free to choose and act. Hope is still better than inaction and despair. And action is better than hope.

After sorrow comes joy, most of the time.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

+++

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

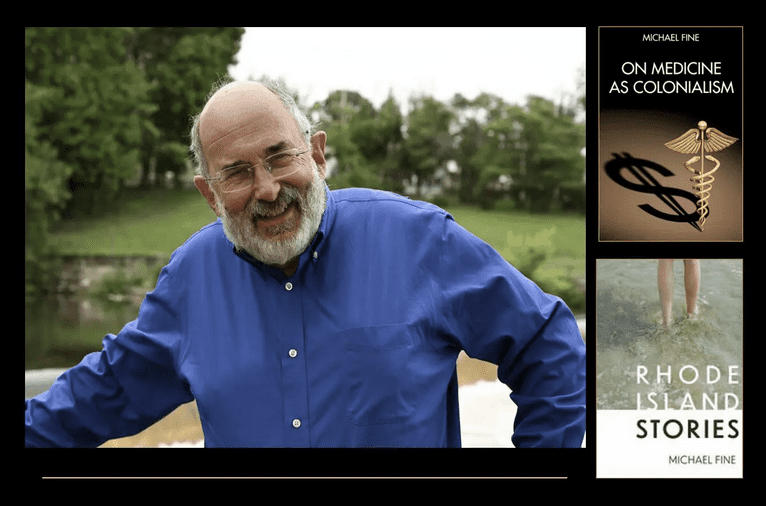

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.