Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for April 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly April 4, 2025

- Groundwater mystery at Budlong Pool revealed during new pool construction. Splash pad opening. April 4, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Trout season up next, know the rules. Sweet’s Hill conserved. Pooch beach ban. April 4, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for April 3, 2024 – Jack Donnelly April 3, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Slow-cooked Octopus & Blanched Sea Bean Salad April 3, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

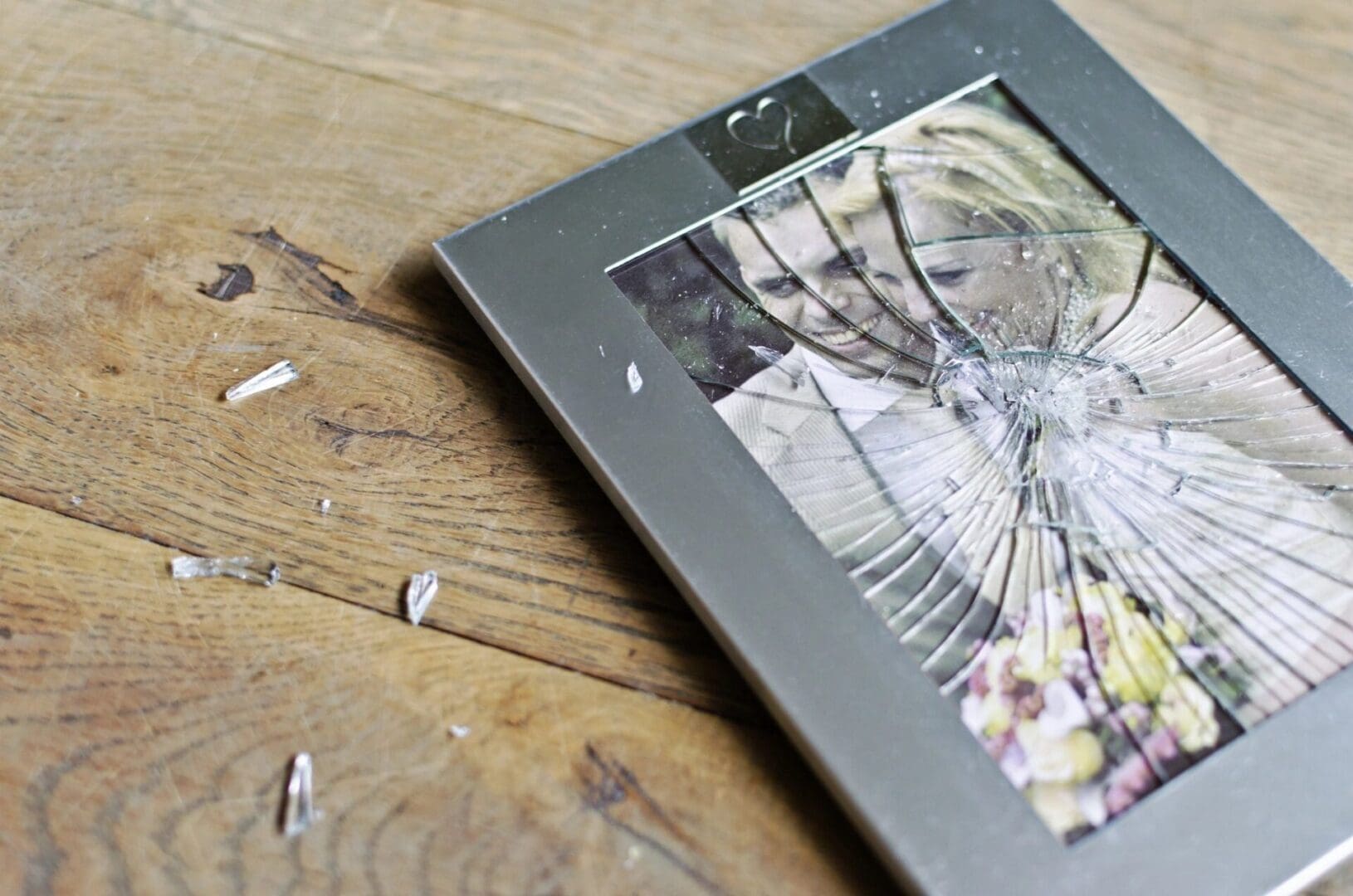

What we do, and call it love – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

_

She knew who he was. Other people didn’t understand what she saw in him — or they had theories about her psychology. Or they used her character flaws to explain her relationship with him. Or thought quietly to themselves about her addiction to physical pleasure, though nothing could be further from the truth on that score. Peter was old, he was corrupt, and he didn’t have one original thought of his own. The big time film maker and producer – that was all a fiction. He worked in film, but as a lighting designer. He made good money, but he made it by running wires and setting up lights, not by directing or doing deals, not even by writing scripts. Did he know the actors? Sort of. He knew who they were. They brushed past him on the set. But that was it. Married four times. Five kids, three with wife number one, and one each with two of the others, the mothers always chasing him for child support. Still married, truth be told. More or less. At least according to Peter. But Dorathea knew that the truth was likely different. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. That wasn’t a Peter thing. She knew who she was dealing with. Ask me no questions. I’ll tell you no lies. He wasn’t fooling anybody. And Dorathea was certainly not fooling herself.

She didn’t call what she felt love. Amusement, mostly. Peter was pretty entertaining, when you got right down to it. Great stories, outrageous stories, so outrageous it didn’t matter whether they were true or not. He made Dorathea laugh, though there was some disrespect buried in her laughter, some acknowledgement that she didn’t think very much of Peter, that she knew he was irresponsible and slimy to his core. One part vanity, perhaps. He liked her, or something. He kept calling. Maybe just because she was an easy mark.

Most women threw him out, cut him off and would never have anything to do with him again the first time he pulled one of his fast ones, one of his finesses, the first time he said one thing and did another, or failed to show up when he said he would or failed to show up at all. Dorathea discarded him then, but only in her own mind. She’d decide to be done with him and wouldn’t answer his calls. And then he’d appear three days later in some fancy new car or with some story so outrageous that you could only laugh.

Peter just kept showing up and he made Dorathea feel like he liked and even wanted her, at least until a new text came or the phone rang. He was present, between the hustles, and at least he was really there, totally and completely with her. Which was spectacular, even if it only lasted for a few hours at a time, or a few minutes. She loved it when he came up behind her while she was washing dishes, locked his hands and arms around her waist and belly and pulled her into his chest and shoulders, his belly and chest full against her back, and nuzzled her neck. She loved it. She just didn’t love him. Mr. Right Now, not Mr. Right.

So when he called her and pitched her that line about his daughter’s husband’s suicide, she listened but wasn’t even close to convinced. He’d told her about his kids before, when she was only half listening because she never knew what was fact and what was fiction, or whether she could believe anything he told her, ever. Darla lived south of Boston and worked for a startup that was hoping to make money in the crypto space, he said, by getting psychologists and social workers who were into on-line therapy to accept crypto for payment. She was separated from her husband, Atul, who was an ER doctor working in Fall River and New Bedford. They had two little girls, eight and ten.

But now Atul had thrown himself off the Braga Bridge in the middle of the night after a double shift at St. Anne’s. He called Darla from his car on his way home at midnight. No, she told him. You can’t come over now. We made a decision. We have to stick by it. We made this decision together. It’s the best choice for everyone.

Atul said okay. He sounded okay. But then he put his flashers on, stopped his car on the bridge itself, where there is no shoulder, got out, walked around his car to the fence that is next to the roadway, the one you look through to see the battleship USS Massachusetts which is anchored beneath the bridge. Then he climbed that fence. Which is six feet high. And is there to prevent suicide. But didn’t.

Then he jumped.

“Isn’t Darla one of the kids who doesn’t speak to you?” Dorathea asked.

‘Rarely speaks to me,’ Peter responded.

“And you’re calling me to tell me this, because?’ Dorathea said, hearing another hustle coming her way. She remembered the $40 K in cash wrapped in plastic that Peter put in her freezer the night of their first date, when he showed up, introduced himself and asked to see the kitchen, all hush-hush like he was a gangster and the mob was chasing him. Dorathea still didn’t know what that one was all about. Or the time he showed up with a litter of German Shepard puppies that he wanted her to keep for him and raise. Purebred dogs, he said. Their mother got run over by a truck. See how cute they are? Can you keep them for me for a couple of weeks, trying to get something for nothing at the same time he was trying to arouse her sympathy for him as woebegone but also someone somehow deserving of love himself.

You just never knew with Peter. What was true and what was fiction. What angle he was working that particular day. And what he was doing just to get your attention, inflame your sympathy, impress you or try to run your life. There was the burner phone he gave Dorathea. That she was supposed to carry all the time. So I can keep you close to my heart, he said. Just for you and me. Nobody else. That he would call her on two or three times a day. She carried it until she figured out that the phone was a scam, a way to take control of Dorathea’s life, using the guise of Peter’s fake romantic bullshit. So she threw it into the pond in the woods behind the house, and threw him out again. Peter disappeared then, angry and hurt. Good riddance to bad rubbish, Dorathea thought. But that thought didn’t keep Peter from showing up again a few weeks later, bringing roses and wearing a naughty grin. And that thought didn’t keep Dorathea from frowning as she stood in the doorway, her arms crossed, but then standing there like a stunned ox as Peter swept back into Dorathea’s life. And what Dorathea thought didn’t stop Peter from taking a call fifteen minutes later, a call he had to go outside for.

“The kids are all shook up. They were just getting used to the separation. And the idea of the divorce. And now this,” Peter said.

“It’s tough, a divorce,” Dorathea said. She had her own history with divorce. “And their father’s suicide….”

“It’s all pretty dicey right now”, Peter said. “We’re all in shock.”

Peter in shock? Dorathea thought. Seemed unlikely.

It was a little house in West Barrington on the water, near the East Providence line, not far from the carousel but hard to get to, buried back among the complicated streets that surround the coves and saltwater ponds of the East Bay.

It was November. The trees were bare. The light was thin and yellow, with the sun lying just above the horizon and the sunlight reflected off the water, making it hard to see. The only leaves were very brown oak-leaves stuck two or three to a branch, on the remaining spindly trees that had survived the great gypsy moth invasion and oak die-off of a few years before. There were gulls floating over the shore, fishing, but the salt air was clean and also fresh and didn’t smell of seaweed or rotting fish the way it often did in midsummer. There was a stiff cold breeze coming off the water.

What the hell am I doing here? Dorathea wondered. I don’t know these people. I’m sure Peter is full of shit, that he’s working some angle again. The new red Jaguar he was driving had dealer plates. Every time Peter showed up, he showed up in a different expensive car. That wasn’t his. Doesn’t Peter need to work today? Dorathea wondered. What the hell is he doing here?

But there were cars parked on the street in daytime. Lots of cars. From all over. Cars parked that way spell sadness, Dorathea thought, and suddenly she felt a certain sadness in her soul, despite Peter, despite everything. This isn’t my family. Dorathea thought. This isn’t my place. It isn’t my problem. I can’t console these people, she thought. But she felt stricken and felt a deep despair nonetheless.

Inside, there were people everywhere, people Dorathea didn’t know, on couches, on chairs and stools and leaning against the walls, shielding their eyes from the fierce sunlight that streamed off the water through the big windows facing the water. The dining room table was covered with platters of food – bowls and platters of salads, pasta, fish, fruit. Cakes and cookies – but almost no one was eating. People touched one another more than you’d expect for a group of this size gathered in the middle of the afternoon. Mothers with their hands on their children’s heads or shoulders. Couples standing arm in arm. Hands on shoulders or the arm of another person. Leaning into one another, so the voices could be subdued. Murmuring. Eyes downcast. People standing close together, not far apart the way they usually stand at gatherings, as if the caution that exists between people, the usual boundaries, had been eclipsed by their collective loss, as if they were falling into one another, looking for the strength to go on. The only philosophical question is suicide, Dorathea remembered. And every suicide makes every person wonder about their own life and choices, about their own suffering, and about the complicity built into the choice to live.

Peter was embraced by one person after the next. He left Dorathea standing in the front hall where people had left their coats stuffed in a small hall closet or draped over the banister of the stairs to the second floor. Awkward. The whole thing was awkward.

Then a woman in her late thirties walked out of the kitchen and embraced Dorathea before Dorathea could react or even step back. The woman had a red puffy face, dirty blond hair pulled back behind her ears and wore a beautiful flowing yellow, orange. red and black painterly dress.

“I’m Darla,” the woman said. “I don’t know what you did to him. Or how you did it. But it doesn’t matter. Thank you for getting my father to show. It means so much to my kids. Their grandfather. Who they hear all these stories about. But isn’t in their lives very much. And they need everything. And everybody. Now.”

Dorathea hugged Darla. Then she pulled herself back. Darla looked Dorethea in the eyes and seemed authentic. She had just suffered an awful loss but now she was holding and consoling Dorathea. Hold on, Dorathea thought. The daughter of a hustler. But not. This woman felt real. No finessing. There it was and there she was. You can tell in a second. This was coming from deep inside her. Who would have thought it?

“How are you?” Dorathea said. And regarded her with depth, the way women see women in times of trouble.

“I’m okay,” Darla said. “In a certain way, someplace deep inside, I was ready. That’s the wrong word. Perhaps I had prepared myself. I knew Atul. I knew his demons. Probably better than he knew them himself. He couldn’t fight them off and neither could I. I just wasn’t strong enough. But I got help and had reconciled myself to what I would never be able to do. There have been other attempts which the girls don’t know about. But I knew. He was overwhelmed by what he saw at work every day, all that suffering that he couldn’t fix, and weighed down thinking that all he was good for was to prolong or the suffering of others. He didn’t want to be here. He couldn’t be the man he wanted to be. He couldn’t be the father he wanted to be. He always felt like a failure, always felt less than, always felt like he was just causing pain and creating chaos for the people he loved. He didn’t want to be in this house, and he didn’t want the girls to see him like this. Suffering. Struggling. He just didn’t want to be here. In a deep way. For a long time. I gave it my best shot, to pull him out of the abyss. But I just wasn’t strong enough on my own. I’m not sure there was anyone who was strong enough. He had to be strong for himself before he was strong for us. And others. And couldn’t. So, I’m okay. But the girls are another story.”

Then Darla looked around at the house full of people.

“TMI for a first meeting,” Darla said, and laughed a little. “We dragged you headlong into the middle of the hurricane. No warning. That’s us. That’s my dad. But you know that already.”

The doorbell rang and three new people came through the door. Darla was pulled into another embrace.

Then Dorathea was alone again. She walked through knots of people into the living room, as she found her way to the window overlooking the water, just to see the sunlight shimmering in the wind-blown waves and the houses lining the shore, which seemed tiny compared to the immensity of the water and the sky, itself filled with mauves and orange as the sun began to set. Then she maneuvered into the dining room, winding her way between all these people she didn’t know and who didn’t know her.

Everyone was taken up by the people they stood with, and by their own sense of impotence and grief. No one noticed her at all.

The two girls sat together in the family room, a dark room off the dining room, with north facing windows obscured by bushes planted close to the house. There were three other children in the room, but they were older and seemed mesmerized by the colors from cartoon characters dancing across the screen on the big TV. Cousins, Dorathea guessed. They’re kids. They don’t know how to handle this.

The two girls sat at a table in a corner by themselves. They were about five and eight. The big one had a big forehead, big green eyes, tan skin and dirty-blood hair like her mother, only it was kinky hair, not straight, and it was pulled back behind her head but puffed out, creating a halo effect. She wore a blue-purple dress that covered her shoulders with stars printed on the fabric. The little one was tiny and had the same cream-colored skin as her sister, but she had very straight black hair that fell to her waist, and she wore a purple velour ballet dress that was too big for her. She seemed lost on the chair on which she sat. There was a jigsaw puzzle open on the table but the girls were staring out the window. What’s with this? Dorathea said to herself. Don’t these people know kids? Know anything?

So she sat down at the table.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m Dorathea. A friend of your grandfather’s.”

The bigger girl didn’t turn toward her. The little girl looked at her sister.

“Is that your dress?” Dorathea said to the little girl. “It’s very pretty. But I bet you got it from your sister.”

“Did not,” the bigger girl said without turning away from the window.

“Did so,” the little girl said, with a voice that was bigger than she was.

“It’s okay,” Dorathea said. “You needed a pretty dress in a hurry. You’re lucky you have a big sister who can help out sometimes.”

The older child looked at Dorathea for half a second and then looked away, as if she didn’t want to be caught looking.

“I’m Amaya,” the younger child said, looking straight at Dorathea.

“I’m Lakshmi,” the older child said, not to be left out. “I’m older. I’m nine.”

“I’m five,” Amaya said. “Going on six.”

“Not until January,” Lakshmi said.

“Going on six,” Amaya said, insisting.

They fell silent for a moment. This isn’t hard, Dorathea thought. Just sad. But someone has to be here. Someone has be with these girls, to listen.

“I didn’t know your father,” Dorathea said. “I’ve heard he was a very good man. I bet you loved him a lot.”

“He was a doctor,” Lakshmi said.

“He worked all the time,” Amaya said. “But he played with us when he was home. Sometimes we went for walks in the woods. Once he took us camping and we slept in tents and made a campfire and everything. He liked the trees. He knew the names of trees and birds.”

“Sometimes he cried at night,” Lakshmi said. “He loved music. Sometimes the music would make him cry.”

“Does music make you cry?” Dorathea said.

“Music makes me dance!” Amaya said.

“But we’re not dancing now,” Lakshmi said. “We’re sad today.”

“I know honey,” Dorathea said. “We’re all sad with you.”

“You’re with us, but we’re still alone,” Amaya said. “We’re sadder.”

“I know honey. I wish we could make the sadness go away. We’re not that smart. Or good, like your dad. But we’re all here. And we all love you.”

Dorathea felt something behind her. A shadow cut off the light from the dining room, which mattered now because the sun was setting.

“Lakshmi! Amaya! What are you doing here?” Peter said.

Both girls squealed.

“You’re quiet,” Peter said as they pulled up to Dorathea’s house. The sun had long set and the air had grown cold. A waxing almost-full moon rose over the roofs of the houses in Buttonwoods.

“It’s nothing,” Dorathea said.

“What? You pissed off at me for some reason? What did I do now?” Peter said.

“It’s nothing,” Dorathea said.

“You were good in there. With those kids. Everybody liked you. Thanks for coming.”

Dorathea sat. She did not unbuckle her seat belt.

“Suzanna was there. So was Christie.” Darla’s mother. And the current wife. “How hard was that?”

“Not hard. I didn’t know who they were. They didn’t say anything to me. Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

“They sure knew who you were,” Peter said.

Dorathea sat for another moment without moving.

Then she turned to look at Peter.

“Do you have any idea what an asshole you are?” Dorathea said. “Just how shitty you are to women? To me?”

“Whaddaya mean?” Peter said. “Me? I am who I am. What you see is what you get. No excuses. And no apologies. Truth in labeling.”

“Fuck you,” Dorathea said. “Go away. I don’t want to hear any of your bullshit. Just get out of my life.” She unclipped her seatbelt and opened the door.

“Don’t call me. I’ll call you. Like never,” she said. “Capiche?”

She stood and slammed the door and walked to and then into her house, without turning around once to look.

Peter sat in the car for a full minute, looking like an ox clubbed by a slaughterer before its throat was about to be cut. Then he grinned, to himself, in the darkness.

Fifteen minutes later he rang Dorathea’s doorbell. He waited a full minute and then rang twice again. He knocked on the door. Then he rang twice more.

Dorathea came to the door in her bathrobe. She had taken her face off and had showered to get rid of all traces of him, and she looked deflated, with thick tired skin and sad eyes that you could see now that the makeup was all gone, and she was barefoot and not even five-two without heels.

“Don’t you understand English,” she said, behind the locked screen door. “I said get out of my life. And stay out.”

“Here, I brought you this,” Peter said, and he brought a bouquet of red roses from behind his back.

Dorathea scowled.

Then she clicked open the screen door so she could take the roses from the idiot’s hands.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

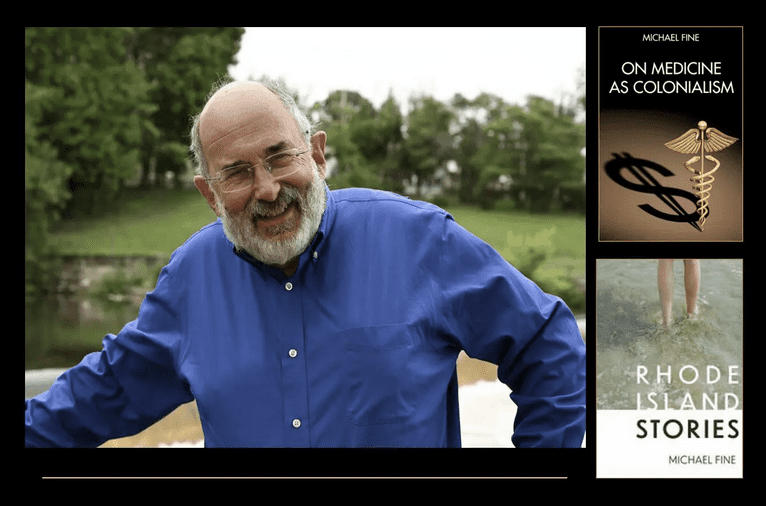

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.