Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Reunions in the time of pandemic

By Richard Asinof, ConvergenceRI

A personal reminiscence on the struggle to preserve your memories

Why is this story important?

The celebration of Earth Day on its 50th anniversary conjures up a number of 50th reunions occurring this year for ConvergenceRI.

The questions that need to be asked

What is the best way to tell the story of environmental activism that grew out of Earth Day? What is the best way to connect the work being done with Childhood Lead Action Project and Save The Bay? How will the disruption of the current economy by the coronavirus pandemic present opportunities to recalibrate the economic equations related to how we value health and climate? When will Venture Café Providence convene an inclusive Zoom meeting of digital news reporters to talk about innovation and climate change and health equity?

Under the radar screen

When I first lived in Montague Center, Mass., a small side-of-the-road town, it did not have a payphone. No one locked their front doors. Neighbors tended to share important news and gossip in daily conversations that were as essential as talking about the weather or the Red Sox. The local postmaster knew everyone’s business.

It was a time in my life of sharp contrasts: I played in the local men’s fast-pitch softball league, on playing fields that ended in hayfields, while at the same time serving as managing editor of the local alternative weekly newspaper. I was recruited by a neighbor to join the local Grange, in an effort to bring in younger members; at the same time that Sam Lovejoy, one of the leaders of the “No Nukes” movement, recruited me [after I left the newspaper] to run the communications for a candidate running for District Attorney. In my professional life, I was writing stories for the New York Times and The Village Voice while I was also creating a TV production company based in Northampton. The first project was to be a video documentary about the separatist conflict in Quebec.

Translated, it was never easy to try and fit all the pieces together in a continuum that made sense, other than creating new patterns each day.

Trying to stitch together four separate strands of my life, all important, from 50 years ago, is an impossible task if you are seeking to establish a straight line of cause and effect. Lives are like that; they do not follow predictable pathways. The art of surviving is very much about learning to let go, not to define yourself just by your work. Call it the art of convergenc

This year, I was scheduled to celebrate four reunions, all marking the passage of 50 years of time since 1970, all connected by a thread of youthful idealism during a time of upheaval, not unlike our current world in 2020.

It was a time when I envisioned my future life as a white board of endless opportunities; all I needed to do was write my plans down, change them if something did not pan out, erase others, rebound from mistakes and draw up new plans, improvising as a jazz musician responds to new riffs.

The father of a college girlfriend, after grilling me for an hour in his study about what my intentions were for his daughter, pronounced that I had “both feet firmly planted in mid-air.” He meant it to be an insult; I in turn took it as a compliment.

In an unpublished memoir, I attempted to capture that romantic spirit of believing in endless opportunities: “We were at a party in a small town in Western Massachusetts, a few days before New Years, as 1967 hastened into 1968. More than two feet of snow had fallen over the last two days, covering our small corner of the Earth with endless cold white – a clean slate upon which it was easy to imagine we could create and follow new paths not yet taken.”

I was a devout believer in the power of serendipity – and in synergy, as defined by R. Buckminister Fuller.

Now, with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the odds that any of the four reunions will be held as in-person events keep dwindling with each passing day. One has already been cancelled and was moved into a virtual mode.

And, with the probable demise of in-person events, there is a growing recognition that my world – and our world – will never, ever be the same again.

Translated, the stories of our lives will be diminished. The rituals around funerals and how we mourn our losses have already been irrevocably changed. To paraphrase Joni Mitchell, it will be difficult to put all the trees in a tree museum and charge money to see them.

The sad reality is that many of the ways in which we share human tales that connect our human past to the future may be erased, wiped off the white board, with no snapshot on our smart phone taken to preserve the memories of events that did not take place.

All the algorithms used to predict social behavior will have to be rewritten into a new code mapping the impacts of physical distancing behavior. What then happens to the older maps? How do we preserve our memories, which may be all that is left us?

Reasons to believe

I write this having to admit to myself that I am also facing a severe limit on my own future physical capabilities. I am having a hard time walking or keeping my balance, as the strength in my legs seems to diminish each day. Something is attacking the myelin protecting my spinal cord in my thoracic region, and after viewing a recent MRI, the neurosurgeon’s prognosis was not good. It is humbling just to keep from stumbling and falling; it haunts and shadows everything that I write.

I have been referred to another specialist for more tests to determine hopefully what is going on, but how long that will take to occur is anyone’s guess in navigating a stressed health care delivery system in the time of pandemic. In my quest to access health care, I have been deploying my best skills as a reporter, being persistent in asking questions and seeking answers.

The condition has not gotten in the way of my professional capabilities in producing the weekly digital news platform, ConvergenceRI; its vibrancy is very much intact.

Why share this story in ConvergenceRI? As we all hunker down in our different modes of social and physical distancing, it is a reminder that our most valuable possession is our own personal stories, and sharing those stories reinforces what makes us human, connecting the past to the future, in order to create an “engaged” community. Call it a synergistic counterforce of convergence in a world where entropy appears to be triumphant. Or, simply, sharing stories in many voices.

Four reunions

The first reunion – the 50th anniversary of the founding of Environmental Action, a group that was born with the creation of the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, has already been cancelled and replaced with a virtual Zoom reunion on April 18.

It’s hard to believe, but Environmental Action was the first citizens group to translate the environmental consciousness of Rachel Carson and “A Silent Spring” into political action and electoral fervor, all under the banner of “Love your Mother,” attached to a photo of the blue orb Earth taken from space.

One of the first political campaigns it launched was to defeat the “Dirty Dozen” in Congress, the elected representatives who took in the most money from polluting corporations. Despite all the odds, the gung-ho political advocacy proved successful, unseating seven of the targeted “dirty dozen” incumbents. The campaign made a direct connection between money, politics and pollution – and tapped into the ability of voters to change their destiny by speaking out and applying electoral pressure.

High school daze

A second, my 50th high school reunion, is slated to occur on the third weekend in October, a gathering of the class of 1970 that graduated from Millburn High School in Millburn, N.J.

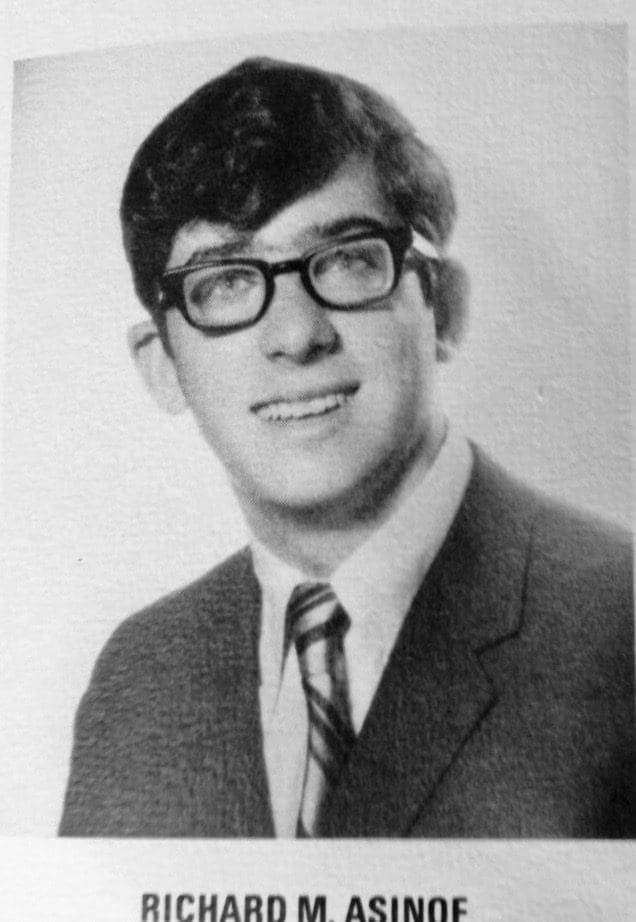

My high school photograph in the yearbook, known as The Millwheel, was later posted in the hallway of the my college’s administration building to show a rogue’s gallery of students who now looked absolutely nothing like their senior photos.

There is a fairly active group of former classmates on Facebook, one where we all have, by counting the years, aged at the same rate of speed. There continues to be surprises in the way in which new avenues of conversation have opened up – conversations that would never have occurred while we were in school together.

There is always a bit of awkwardness for me when I have attended previous high school reunions, as they served as a cogent reminder of all the reasons why I have chosen not to live in New Jersey. My high school memories have been punctuated by my experiences, sometimes painful, by what happened when I stood up and said no. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A willingness to stand up and say no.”]

Getting physically assaulted by a football coach in the front hall of the school for something I had written in the high school newspaper, as he banged my head against the wall, screaming at me, was something I scoffed at when it happened. But today, I realize, that such incidents created some deep emotional scar tissue, with some of the shrapnel still working its way out.

Non satis scire

A third reunion, slated for the same date as my high school reunion, the third weekend in October, is my 50th college reunion, marking the first class entering Hampshire College in the fall of 1970.

As has been covered by the news media, the last year has been a tumultuous one for the experimental liberal arts college, surviving an effort by the former president to merge the school with the University of Massachusetts Amherst campus. In the aftermath of that disaster, the college is now attempting to reinvent itself, an incredible feat all in itself.

I have written about the qualities of my education at Hampshire being defined by an unlikely quartet of conversations I had with John D. Rockefeller III, Charles Mingus, John Updike and Anais Nin. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Let us now praise the importance of asking questions.”]

If not now, when?

A fourth reunion, if it is held and if I am invited, will be for the 50th anniversary of the Urban Mitzvah Corps, a program I co-founded in New Jersey. The origins of the program were born from my experiences tutoring a single mother, Mrs. Mott, in mathematics, to help her to pass her high school equivalency test.

Every Saturday morning I would travel to the Fuld Community Center in the Central Ward in Newark, and work with Mrs. Mott on basic algebra and geometry formulas. It was 1969, less than two years after the July 1967 riots had burned down much of the neighborhoods surrounding the community center – which had been built originally by a Jewish philanthropist to serve immigrant families at the turn of the century.

The tutoring had begun as a program sponsored by my local temple youth group, but was abruptly shut down when some of the temple’s elders found out about it and deemed it to be too risky.

Mrs. Mott and I agreed to continue our tutoring collaboration. And, yes, she did end up passing her high school equivalency test. That experience seeded the idea that creating a summer program of interactions between Jewish teenagers and the African-American population in a volunteer setting would do much to further better racial relationships in a time of fear and unrest.

The fact that the Mitzvah Corps program has survived – and even thrived – is still a wonder, given what it took to create the program, raise the money to support it, convince the “adults” involved to permit it to happen [the big compromise involved was to move the location from Newark to New Brunswick], and recruit teenagers to attend the first summer session.

It is a tale where I have, for the most part, been written out of the history of what happened, for a host of different reasons.

Earth Day

But because this week marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, and with it, the celebration of Environmental Action, the group created in its aftermath, it seems worth taking some time to reflect upon what has happened to the environmental movement in a time of pandemic and climate change threats.

In 1982, I was recruited by Scott Ridley, a fellow member of the affinity group, “The Miso Hornets,” which I had joined at the last minute before the occupation of the Seabrook nuclear power station in 1977, where I had been covering the event as the managing editor of The Valley Advocate in Amherst, Mass. At Environmental Action, Ridley in 1982 was the editor of a journal about electric utility policy news, called “Powerline.”

For three years, I served as an editor at Environmental Action magazine, from 1982-1985, as well as the first communications director for the national environmental group. The offices of the magazine were in the corner office, so to speak, on the seventh floor of the iconic triangular Dupont Circle Building, looking out onto Dupont Circle. Although the organization folded its tent in 1997, stalwarts and veterans continue to keep the flames alive of a time when citizen activists rose up and changed the political equation.

The reunion took place on Zoom on April 18, with more than four dozen participants.

I have often thought about writing a journalistic piece about the disconnect that happened to the environmental movement and the efforts by a new generation to lead the fight against the threat of climate change. I had hoped that I would be able to interview participants at the reunion, capturing their thoughts about why the political advocacy of Earth Day had not proven to be sustainable, given the rampant rollback of environmental law and regulations during the Trump administration, including the latest plan to allow increases mercury pollution.

A recent op-ed in The Seattle Times by Denis Hayes, one of the original folks who helped create Earth Day and found Environmental Action, published on April 12, attempted to move the traditional celebration of Earth Day on April 22 to Election Day on Nov. 3, closing with the argument: “This November 3, vote for the Earth.”

The editors at Environmental Action magazine produced a quality of reporting and analysis unmatched by many other environmental publications in that era. We covered the sordid stories of toxic waste, toxic torts, and toxic crime, in the age when the Environmental Protection Agency was busy doing sweetheart deals with corporate polluters, run by Anne Gorsuch Burford [the mother of current Supreme Court Justice Gorsuch] and Rita Lavelle.

We were one of the first publications to report on the threat of climate change. In 1985, to celebrate the 15th anniversary of Earth Day, we published a special issue called “Visions,” trying to imagine what the future would be. Few of our predictions proved prescient. In 1997, the organization folded its doors.

Building bridges

Often in my work at ConvergenceRI, whose mission is about breaking down the news silos around coverage, I have sought to develop collaborative reporting relationships with organizations such as ecoRI News, including an effort in 2016 to support “Bee Vigilant,” to educate folks on the importance of protecting pollinators from lawn chemicals and toxic pesticides and fungicides. [See second image.]

I have attempted to cover developments in local agriculture, such as the African Alliance of Rhode Island and the successful efforts to keep a farm in Barrington as a working farm, turning it into an educational enterprise known as the Barrington Farm School.

I have been happy to re-publish stories run by ecoRI News, and they have done so, when appropriate. Still, I wish there were more opportunities to engage in such collaboration, tearing down the artificial walls around the concept of scarcity.

Root causes

Why did Environmental Action fade away? It is a question I have often pondered. Some of the problems with Environmental were structural, some were financial; others were generational. Beginning in 1977, when the new Carter Administration came to power, Environmental Action became more dependent on government funding and non-profit foundational grants, expanding its scope into toxics and hazardous waste, and increasing its staffing. In 1981, with the Reagan administration, those monies vanished, and the tensions between the foundation arm and the political arm of Environmental Action became more pronounced.

In 1984, a number of the foundations involved in funding environmental groups attempted to create a merger between Environmental Action and Friends of the Earth. The alleged aim was to find new strength in combining the programs of the two environmental advocacy organizations, similar to what is being urged today by many funders to combine social work programs to achieve greater success. The reality, however, is that the real mission was to enable foundations to cut their investments in environmental work.

The failed attempt at merging the two organizations, instead of creating greater harmony between the two groups, resulted in heated conflict and enmity. Further, it tore apart the internal staffing politics at Environmental Action.

One of the important attributes of Environmental Action was its non-hierarchical structure and its commitment to consensus decision-making, even in times of financial distress. The willingness to achieve consensus as a group in creating agendas and policies was an important part of the organization’s success, even if it is omitted from the historical narratives.

Everyone who worked there made the same salary, some $19,000 a year. Most of us lived in houses shared with other young professionals who had sought out employment in the District. There were epic volleyball games in an informal league and softball in the summer was a highly competitive affair. One annual highlight was the Public Interest Follies.

Some other memories: In February of 1983, there was a huge blizzard that shut down Washington, D.C., for days. My response was to put on my x-country skis and ski into work through Rock Creek Park. Later that night, after numerous impromptu gatherings, I skied back to my home, as residents outside on the street gawked at my presence gliding up and down the hills back home.

In 1984, as part of a tour promoting a new report on “Rate Shock” – the extra charges that utilities were charging customers for the costs of nuclear power plants – a colleague and I traveled from New Hampshire to Philadelphia to Chicago to Kansas City to Houston to publicize the report. In Chicago, I formally endorsed Sen. Paul Simon for re-election for Environmental Action in front of the headquarters of Commonwealth Edison before a scrum of reporters, cameras and microphones. [When the event was edited and broadcast, I was cut out of the scene.]

Also, in 1984, in the aftermath of the toxic cloud in Bhopal, India, that killed thousands, I ended up going on ABC’s Nightline and then wrote an op-ed for The Los Angeles Times.

What I treasure most, however, were the moments of teamwork with my fellow editors: Jim Jubak, Francesca Lyman, Kathy Hughes and Rose Audette, who, like soldiers in a trench at the front lines, supported and encouraged each other and perhaps, more importantly, learned to accept each other’s edits.

This Earth Day, it seems, all of us will need to celebrate it alone, yet together, finding ways to connect ourselves to our neighbors yet still keeping our masks on and keeping our social distance to stay safe.

One thing the coronoavirus pandemic has taught us, hopefully, is that we are all living on the front lines of enormous upheaval in our disrupted world – disruptions that promise to become more frequent as the realities of climate change become more pronounced in our lives.

There is still a need, no matter how hokey it may seem, to be able to express a sense of wonder and connectedness when we say: “Love your Mother.” It is a way to say: we need to love and honor and respect ourselves.

Richard Asinof is the founder and editor of ConvergenceRI, an online subscription newsletter offering news and analysis at the convergence of health, science, technology and innovation in Rhode Island.