Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 5, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 5, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Framing the classical revival – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There – contributing writer

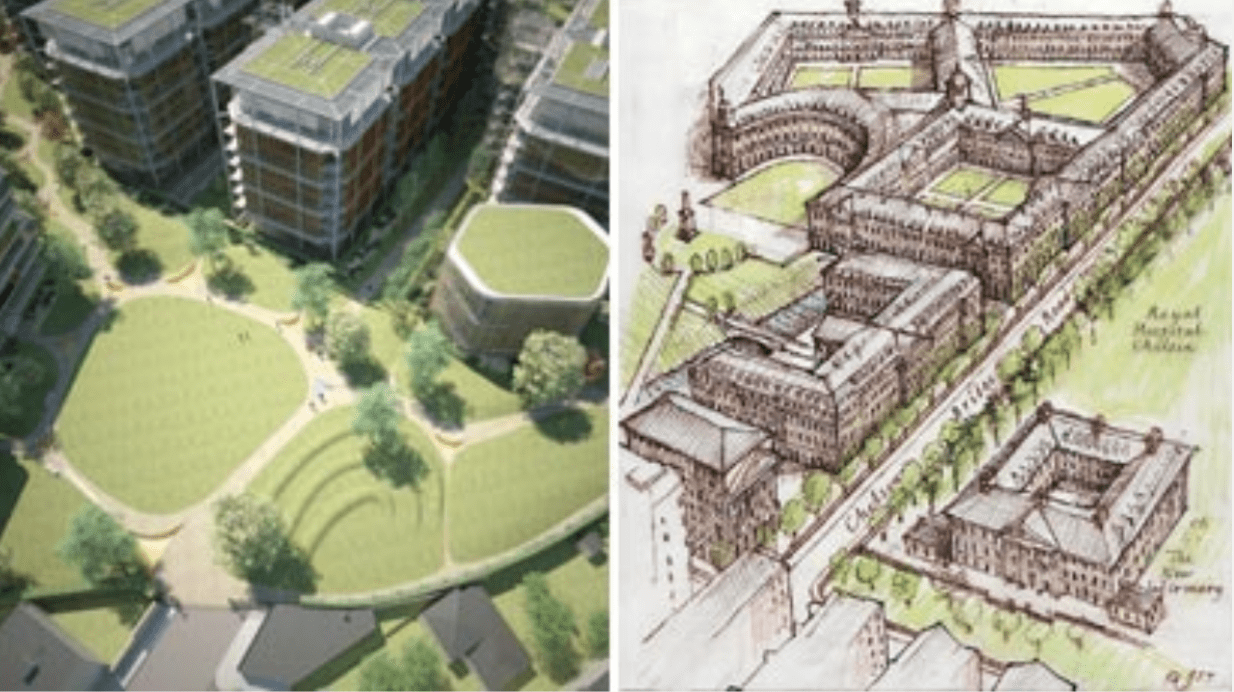

Photo: The modernist Richard Rogers plan was outvoted in a survey by Quinlan Terry’s traditional proposal by 67 percent to 33 percent, but what was eventually build is an unsatisfactory compromise.

Here is a post written in May of 2014. Of the major efforts within the past decade to oppose modernist urban projects or to support traditional alternatives, mentioned below, most have failed. The Gehry Eisenhower memorial opened in 2020 largely as originally designed. Clemson seems to have been moved by widespread public opposition in Charleston, S.C., to a modernist architecture building at its campus there. Now it seeks to put the new building in a lovely old house blocks away from the historic city center.

After strong public opposition and the intervention of Prince (now King) Charles, the proposed modernist residential/office complex at Chelsea Barracks, in London, was blocked, but the public’s preferred design by Quinlan Terry was blocked by an unsatisfactory compromise. Construction of the planned 42-story pyramidal tower in Paris called The Triangle designed by Herzog & de Meuron began last year and is scheduled for completion in 2026. Efforts to block it in the French court system failed. Other Paris skyscrapers are pending. The proposal to rebuild Penn Station, in New York City, as originally designed by Charles Follen McKim remains one of several proposals, all of which are mired in the tangled politics of New York State transportation policy. Public participation clearly has a powerful impact on architectural development, but thus far it has not shown itself to be capable of pushing aside the even more powerful forces of establishment modernism.

Next for the classical revival

May 24, 2015

What those who favor traditional architecture should do to promote its revival has been pretty much the subject of this blog since I started it in 2009. In fact, the strategy I favor has the advantage of being under way already. It needs merely to be shifted into a higher gear.

On Friday, I received an email that proposed using the word admirable in place of the word beauty. Then another person wrote in to defend the word beauty. Yet another person remarked that “something is emerging” in response (I think) to an email hailing a “New Classical Discourse.”

I must say I too prefer the word beauty over admirable. Admirable is too general. That may be its allure to some – it lacks the baggage that the modernist discourse has loaded upon the word beauty. Admirable is indeed an admirable word and concept, but it cannot fill in for beauty.

The whole idea of debating over new words to promote existing ideas strikes me as typical of the sort of discourse that, fascinating as it is, keeps us little by little from taking action to bring beauty back into mainstream of practice in design and building.

It seems to me that the New Classical Discourse is also a distraction from the main thing traditionalists should be doing – pushing tradition, or classicism, or beauty, or admirability – in the forums that have the power and the responsibility to shape our built environment. Those forums are city councils, design review committees, development authorities, even the newspapers, where events at the former venues are reported.

I have broached this topic a number of times on TradArch and Pro-Urb and in my blog posts without much response. I realize what I am suggesting is difficult because it goes up directly against force of influence in the real world rather than talking amongst ourselves (in the “garden party” or elsewhere) about nomenclature, framing, etc. Again, all quite vital but secondary if the goal is to bring new traditional work into the mainstream of architectural practice and the development process.

We can use existing organizational structure to promote this strategy. Indeed, it is already begun without an organizational structure. It is the work done publicly to derail the Gehry design for the Ike memorial. It is the work done in Charleston to stop Clemson’s monstrosity and to build a more reasonable political infrastructure to oversee new development there. It is the work done by the New Urbanist movement to revive principles of community that worked for hundreds of years. It is the work done in Britain to use public opinion polls to derail a Richard Rogers project in favor of a traditional project by Terry Quinlan for Chelsea Barracks. It is the work done by SOS Paris to oppose plans to build skyscrapers in the City of Light. It is the proposal in New York to rebuild Penn Station as it was originally designed by Charles Follen McKim. It is every activist descent upon the meetings of public agencies, every letter to the editor from someone peeved by ugly new buildings and anti-urbanist projects being developed in cities and towns around the country, every effort to mobilize opposition to the further degradation of our communities.

I think the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art would be the most effective existing institution to expand this broad effort through its 15 chapters. To the extent that people have not hit the mute button on our increasingly ugly built environment, they favor traditional buildings and places by a large margin. [The ICAA stepped back from participation in this battle when it struck “advocacy” from its mission statement and barred chapter board members from using the ICAA name in its opposition to projects to which they object.]

Architects and those who support them have a responsibility to the public. The late Roger Scruton described the public as the “great disenfranchised majority of users of architecture.”

And I think that the goal should indeed be to move forward by reaching back to the already-existing answer to the problems that have beset architecture, planning, cities and the built environment. We do not need a “new discourse.”

Yes, we should reach back to the classicism and the traditions interrupted before World War II by modernism, and move forward within that tradition, adopting to changes in program and improvements in technology and materials as architecture has always done, learning from past practice, including modernism, as architecture has only lately ceased to do.

The reply will come that young people are not with us, that they consider traditional architecture to symbolize a history that they find embarrassing. I think this impression is false, generated by those who spend too much time listening to the wind blowing through the groves of academe – where generating social angst has become a cheap alternative to seeking practical answers to the real problems of the world. It’s not that such complaints entirely lack validity – it’s just that most people in the real world beyond campus walls pay them little mind, and that discourse has little to do with architecture.

In short, I think we should concentrate on an action program seeking to push forward with an already existing ideal that answers every question.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451.