Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Turkey talk, conservation news, comedian picks RI, Greenway, holiday lights, 2A November 22, 2024

- Business Beat: Bristol County Savings Bank promotes Dennis F. Leahy November 22, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for November 22, 2024 – Jack Donnelly November 22, 2024

- Thanksgiving 2024. Love, Family, Remembrance, Fear, Loathing – Mari Nardolillo Dias November 22, 2024

- Find the right vein, first time, every time. NEMIC, VeinTech partner to bring ultrasound tech to US November 22, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

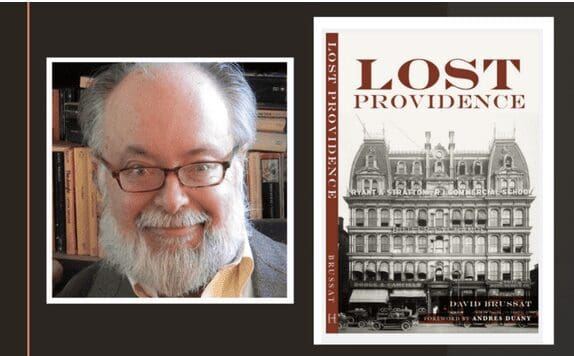

Lost Providence: “Waterplace and WaterFire” – from whence we came – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Editor’s note: Here this blog resumes republication of chapters from Lost Providence, published in in 2017. I took a break from that series in order to write about pressing new matters. At that point I had published chapters 15-20, from Part II. I had decided not to republish Part I of the book. I may change my mind at a later date, but I should leave new readers with some reason to buy the book, right! I resume today with the first half of Chapter 21, “Waterplace and WaterFire.” Here is the first half of that chapter:

***

The encirclement of Waterplace Park by sterile modernism terribly degrades the experience of visiting the park, but objectivity requires admitting that in one sense even these buildings serve a useful purpose (aside from housing people and their activities). In surrounding the park with their bulk and height, they provide it with “walls” that transform the park into the sort of outdoor living room that best defines public space in a city. This creates the sense of enclosure that people crave in a civic square.

But even this service might have been inadequate to the needs of the park as a public space were it not for the extraordinarily attractive infrastructure designed by [the late] Bill Warner [The Rhode Island architect and planner hired by the state DOT to design the city’s new waterfront].

The soft edges of the pond; the many ledges to sit on; the rusticated granite abutments salvaged from the old embankments; the cobblestone pavements; the old and new stone of the walls between the multiple levels of walkways; the gentle arcs of the classically inspired bridges flanked by arched openings to passageways carrying river walks beneath twin pedestrian spans; the stylish and often witty embellishment of bollards, lampposts, tree grates and railings lining the rivers, walkways and parks – all of these humanist features forge both a conscious and an unconscious simpatico among the project, its buildings and the people who stroll amid its precincts.

These features serve as a saving grace at Waterplace Park, since they form an aesthetic bulwark against the glass-and-steel chill of the buildings that make up its outdoor room. The charm of the beauty that we walk by and see close up overwhelms the sterility of the buildings that occupy that western section of the waterfront. The “deep structure” of infrastructure softens the superstructure of Waterplace’s architectural build-out. It ties the two sections of the riverfront together, to the advantage of both. All these elements that save the bacon of the modernist western riverfront serve to lift its more traditional southern stretches to a degree of beauty unknown in contemporary waterfront redevelopment around the world.

Unlike the waterfront’s stretch along the Woonasquatucket, its stretch along the Providence sits between parts of the city fully built up for many years. Heading south from the confluence, a row of historic institutional and academic buildings along the east embankment, including Market House, heads into Memorial Park, whose central feature is the World War I monument by Paul Cret, relocated from Suicide Circle.

The buildings that create the “room” of architecture around Memorial Park are Market House (1773); RISD’s College Edifice (1936); Providence County Superior Court (1933), with its cupola and its gabled wings climbing up College Hill; and the commercial buildings down South Main Street, starting with the counting house with the baroque ogee gable that was originally designed as his own residence by Joseph Brown in 1774, and concluding with the domed Old Stone Bank (1898) and its neighbor, the Benoni-Cooke House (1828).

The panorama of these buildings amply displays the symphonic aspirations of classical brick. As an accomplishment of two centuries of creative architectural craft, the cityscape of College Hill is downright inspirational. The clunker at its southernmost terminus, Old Stone Square, is insufficiently obnoxious to destroy the view. The building is tremendously obnoxious, but not enough so to ruin the masterpiece of its setting.

It is a setting that looks across the river to downtown’s Financial District, a crescendo of new and old towers that epitomizes what a city skyline should look like. This skyline has been remarkably stable, its last tower arising three decades ago, the Fleet Center – a postmodern building whose stepped gable is said to pay tribute to the Industrial Trust “Superman” Building (1928). Joined by the city’s first high-rise, the Banigan Building (ten stories, completed in 1896), the Turk’s Head Building (seventeen stories, 1913) and the Old Hospital Trust Building (eleven stories, 1919), the skyline’s modernist contributions are conservative, upstanding fellows that do their duty, contributing to the civic crescendo to the best of their ability, which reflects modern architecture at the utmost of its potential for achievement. They are the Textron Building (twenty-three stories, 1969) and the Hospital Trust Tower (thirty stories, 1974).

The Textron’s windows are deeply recessed into a concrete-aggregate grid that rises with more solidity than the seemingly insubstantial glass and travertine of the Hospital Trust, which looks as if a stiff breeze could push it over. Yet both contribute admirably to the skyline – far more so, however, as seen from College Hill or downriver than from Kennedy Plaza or Waterplace Park. From the latter angles, the skyline seems less to lift the heart than to toe the line of march. (Oddly enough, it is this less-appealing angle that seems to enchant most of the city’s iconographers.)

Although the Providence River stretch of the waterfront runs through a mixed architectural environment of traditional and contemporary buildings, both the immediate vicinity and wider context are dominated by historical buildings. Thus the generally traditional elements of Warner’s waterfront design reinforce rather than undermine the dominant theme of the city, of diversity amid unity.

It is very important to keep in mind that innovation, whether old or new, is baked into an environment in which those artists called architects paint beauty onto a canvas that evolves over generations of work, often with one building replaced by an even more attractive building. In turn, that context strengthens the allure of the waterfront infrastructure and all of its ornamental paraphernalia. Turning the pages of the several compilations of new waterfronts around the world, published over several decades by the Waterfront Center in Washington, D.C., one learns to appreciate the unique beauty of Providence’s new waterfront.

***

Editor’s note: That concludes the first half of Chapter 21, “Waterplace and WaterFire.” The next post will conclude the chapter.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451.

These buildings that sit doing nothing is crazy, fix them up and give people affordable places to live

Water place park is an absolute WASTE