Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

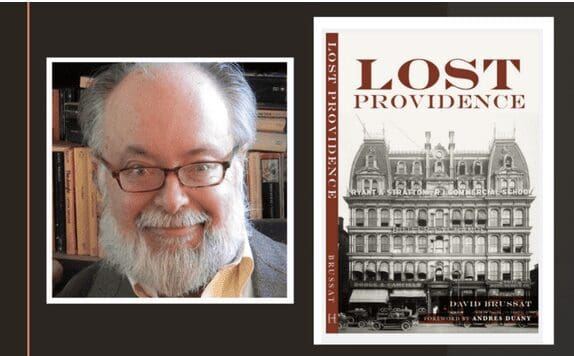

Capital Center BuildOut – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

As you will or maybe already have seen, flipping the order of Chapters 19 (“We Hate That”) and Chapter 20 (“The Capital Center”) in this reprint of Lost Providence has predictably caused problems. Specifically the need to explain, at the start of Chapter 20, what “the analysis in the last chapter holds water” refers to. It refers to the idea that using traditional design, as Mayor Paolino did in reopening Westminster Street, will strengthen the historical character of Providence. The Capital Center build-out, in its three phases, demonstrated how that insight can be understood and misunderstood, as described below.

***

To the extent that the analysis in the last chapter [Chapter 19, “We Hate That”] holds water, its workings may be seen in the three phases of design at Capital Center referred to in Chapter 18. Rolling out over two decades as if somehow ordained by a confused zeitgeist lodged in the Capital Center Commission’s evolving worldview, the district’s first ten buildings break down into three successive phases of postmodern, traditional and modern architecture.

The first four buildings arose as the streets, bridges, river walks and new river channels took shape in the mid-1980s and early 1990s. Together, these four buildings are a tutorial on postmodern architecture. Providence Station, the new, relocated depot completed in 1986, was modernist, even mildly brutalist – a low flat slab of limestone sheaths with a square clock tower and shallow stainless-steel dome. The dome was said to evoke the State House dome, but it was shorn of detail, winking at tradition. The second building, a low-rise office complex called the Gateway Center, completed in 1989, snuggled up to tradition with its green, faux-copper attic roofline and bowed central front, but it kept its distance with flanking concrete façades embellished, unenthusiastically, with classical stringcourses. The third building, a residential complex called Center Place completed in 1990, also doffed its cap to the Platonic ideal of “a building” but expressed its reluctance with shallow detailing in its brick and precast façades, into which square windows were “punched,” as modernists like to say.

The fourth building, a triangular brown office tower called Citizens Plaza, was completed in 1990 on a temporary island as the new channels of the relocated river confluence were laid on either side of it. Violating one of the key principles of the Capital Center guidelines, it blocked views of the State House from downriver. A sliver of its dome and the Independent Man can still be seen squished between Citizens Plaza and the Hospital Trust Bank building. The triangular building seems to imagine that its three very slightly classicizing towers, capped at each corner, make up for the sin of closing down a major view corridor. Not.

Those four buildings were followed by three buildings along the western edge of the district, beyond Waterplace Park and across Francis Street but still on parcels attached to Capital Center. These three buildings arose in the last half of the 1990s, advancing beyond the hodgepodge of the district’s postmodernist beginnings. They spoke in the traditional language of architecture that had characterized Providence for more than three centuries.

The Westin (now Omni) Hotel, a publicly financed facility connected to the newly completed Rhode island Convention Center in 1994, boasted actual gables, tinted green as if copper, atop a base of cast concrete and a shaft of brick. I cut my critic’s teeth during the review process for the Westin, during which Brown architecture historian William Jordy, quoted in my Journal column “A Review of design Review” (February 18, 1992), said he wanted it to be “more modern and less archaeological.”

To their credit, the [Westin] architects did not make the major changes that the initial criticism seemed to call for. How could they? The criticisms were vague to the point of pointlessness: The hotel design was a “pastiche,” it wasn’t “honest” enough. It resembled other buildings in other cities too much.

The second building was Providence Place, completed in 1999. its two classicized anchor stores were connected by a factory mill-like central stretch of brick with a three-story glass “Wintergarden” that bridged the river and the railroad tracks that ran beneath the mall. Because of its complexity and its size, extending from the Westin Hotel to the Masonic Temple near the State House, about four hundred yards, its review process was lengthy. Architects for the two anchors, Nordstrom and Filene’s, designed each end in robustly classical styles; the middle picked up on the city’s industrial heritage. Friedrich St. Florian, who soon after designed the National World War II Memorial on the Mall in Washington, D.C., was in overall charge of the exterior design. By the end of the long review process – which reflected the same inanities that had slowed the Westin design – the mall managed to retain an unapologetically traditional appeal.

A surprising earlier design for Providence Place was proposed by the office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, whose Marilyn Jordan Taylor did the original master plan for Capital Center. A principal of that firm, Adrian Smith, inked a thoroughly classical design for Providence Place. His work on the mall suggested not only the eclecticism of the architect but his bravery, embracing American Renaissance heritage amid a period of aesthetic angst among members of his profession. Smith – who recently designed the Burj Khalifa, in Dubai, the world’s tallest skyscraper (for now) – saw his mall design jettisoned after former Outlet Company CEO Bruce Sundlun, who supported the mall project, lost the governorship in 1995. He was succeeded by Lincoln Almond, whose campaign had deployed a shifty opposition to the mall or, more precisely, to its proposed “tax treaty” with the city and state. Almond’s critique evaporated soon after his election, followed by the hiring of St. Florian to lead the mall’s exterior redesign.

The third traditional building was the Courtyard Marriott Hotel, built between Union Station and Memorial Boulevard with a sweet yellowish brick from the same quarry used for the Union Station and trim of burnt sienna (as Crayola denotes this color). The hotel, completed in 2000, was a larger version of Union Station’s five brick rectangular structures, the easternmost of which had burned down in 1941 and was not rebuilt until 1984. That its design program replicated the lost building’s style rather than “following a different drummer” was another indication that an inclination toward the city’s traditional appearance was trying to reassert itself.

These three new buildings demonstrated one of the abiding merits of traditional styles. They love one another. And they do not need to be perfectly suited to one another, or especially beautiful, to do so. Viewed from either downtown or from the governor’s balcony of the State House, the three buildings (plus a traditionally designed residential tower added to the Westin complex in 2004) evoke the camaraderie of the classical orders: they gentle the condition of Francis Street, illustrating the complementary nature of architecture that stems from the classical orders. Neither the mall, with its serial cupolas, nor the westin towers that dominate either view are paragons of classical virtuosity; their ornamental detailing ranges from somewhat lame to downright clunky. Yet they smile at the pedestrian, who has something nice to look at for a change, and whose belittlement alongside such large buildings is minimized by the palette of scales incorporated in these structures, urban and urbane.

The view from downriver toward this set of traditional buildings just beyond Waterplace spoke with equal force to the same principle of architectural camaraderie. The photograph (three shots above) by Richard Benjamin, a former photographer at the Providence Journal, looks like a painting, and not only because of the smattering of happy clouds in the sky over the horizon. Shot in 2000 near dusk at the outset of a WaterFire (more later on this phenomenon), the three traditional buildings form a splendid backdrop to Bill Warner’s traditional infrastructure at Waterplace Park. Had the Capital Center Commission continued to plan the district’s future based on a reverence for its past, Providence would have found itself blessed by the most unique new urban center in the annals of modern American planning.

***

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451