Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 5, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 5, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 05.06.25 (Rental help, events, resources) – John A. Cianci June 5, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Rosemary-Lemon Statler Chicken, Yukon Golds, Haricot Vert and Dijon Demi June 5, 2025

- ICE arrests nearly 1,500 in Massachusetts. First part of “Operation Patriot” – Nantucket Current June 5, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 4, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The architecture of ballet – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing architecture writer

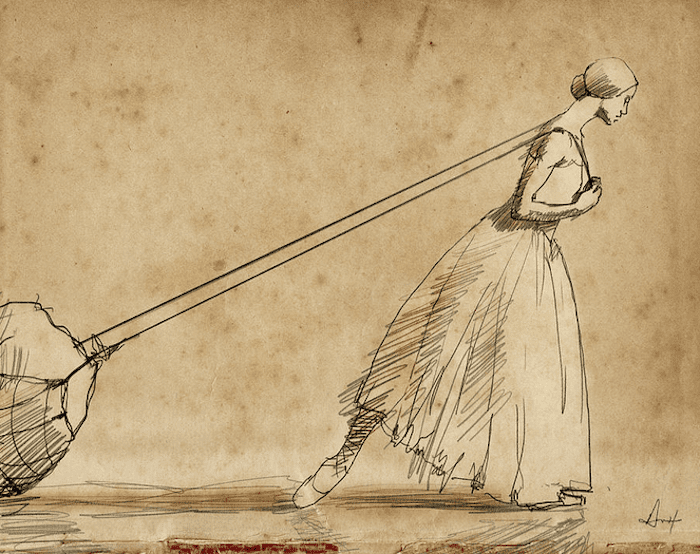

Photo: Ballerina drags world’s problems into ballet. (H. James Hoff)

On Father’s Day we took in “Emergence,” a maskless program by Festival Ballet Providence celebrating the ongoing state of unlockingdown in which American society, at long last, finds itself. It was an excellent show. To my mind, the spare setting in the FBP parking lot beneath a beautiful azure sky did not diminish the performance of four pieces, two of modern dance and then two of traditional ballet. But the setting did recall an essay I had finished earlier in the day by Robertson Davies, the Canadian novelist and jack of all literary trades.

“How to Design a Haunted House” was actually a lecture, or speech, delivered in 1960 to the Ontario Association of Architects, whom he twits for (among other things) the decline of theater architecture. He writes:

Let us begin with the Drama. You people have just about killed it because of the revolution you have brought about in theatre design. There was a happy day when we had wonderful playhouses, with terrible scenery: now you have given us terrible playhouses with wonderful scenery. … [Regarding the new theaters], they were not temples. … Maybe they had Stereo-Structural Sensualism; there seemed to be an awful lot of naked steel showing in some of them. I am so old-fashioned that it still makes me ashamed when I can see what holds a building up. It is honest, I know, but where is its charm? Such painfully honest architecture might perhaps be called the New Immodesty.

Back to the Festival Ballet’s “Emergence.” Much as it would fit into my usual narrative, I cannot say that the difference between the first two dances and the last two dances was in the degree of ornament. The dancers were to a last man and woman beautiful in face and physique, and their movements were evocative of— of what? The modernist dances featured purposely stiff, often machine-like choreography, with abrupt movements suggesting displeasure via a concavity or angularity of form in the plasticity of bodily shape, often with blank looks and even frowns on the faces of the dancers. Whatever the meaning imparted by these two pieces, they seemed to repudiate the beauty of the dancers themselves.

The classical dances were, as one would expect, lovely, smooth and elegant. The choreography and the movement of the dancers’ bodies, limbs and faces seemed to exalt their physical and facial beauty. The very expressions on their faces danced just as surely as the movement of their bodies and limbs. For the first time that evening, smiles could be seen on the faces of the dancers. Their movements told a story much more legible than the stories told by the modernist dances, which challenged viewers to construct their own interpretation of the meaning of the piece. Apparently, these interpretations aimed to fill viewers’ minds with the angst of our era.

Obviously, the modernist dances were intended to make the audience think – otherwise there would be no point to them. Neither the choreography nor the dancers’ movements were beautiful, nor were the ideas they seemed to convey. The traditional dances were intended, on the other hand, to cradle the minds of the audience in feelings that had characterized ballet from time immemorial – along with music that accompanied them. The aim of the traditional dances was to give pleasure. The audience knew what to expect of the traditional pieces, especially the romantic pas de deux set to Chopin, and had little idea what to make of the modernist pieces. I am sure that to do the excruciating work of classical ballet well is a much more difficult artistic feat for the dancers.

So in the end, the performance as a whole did end up fulfilling my usual narrative. The difference between classical and modern ballet does reflect the differences between classical and modern architecture. It is easier for an architect to design a modernist building because it need not conform to practices and principles that have evolved over centuries to create beauty – a goal that most modernist architects have removed from their repertoire, so difficult is it to achieve with the tools in the modernist toolbox. Dare I suggest that modern ballet risks accomplishing the same achievement?

A university is likely to receive more donations from alumni if the beauty of the school’s campus grows in the lifelong memories of its graduates. So, likewise, a ballet company will probably win more patrons and donors if its programs favor beauty and tradition over intellect, novelty and their abstractions. In the program guide for “Emergence,” the company director, Kathleen Breen Combes, writes:

These performances represent the wide range and scale of what Festival Ballet Providence has to offer, from delightful and powerful stories, to bold, new works reflective of today’s artistic voices.

Truly. And I am glad that the company has dancers who can dance both styles of ballet. To like one style does not require audiences to dislike the other. But the Festival Ballet’s future compels its directors to approach programming decisions without indulging in fuzzy math or wishful thinking.

To read complete article: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2021/06/20/the-architecture-of-ballet/

_____

David Brussat – My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/