Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Legislature Highlights Accomplishments for the 2025 Session June 25, 2025

- Sports in RI: Cody Tow, Volleyball Past, Present and Into His Future – John Cardullo June 25, 2025

- Need a Break? Time for Sour Grapes – Tim Jones June 25, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather Forecast for June 25, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 25, 2025

- It is what it is: Commentary on 6.25.25 with Jen Brien June 25, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

$20/hr start for direct care workers for adults with developmental disabilities – Gina Macris

By Gina Macris, Developmental Disabilities News, contributing writer

The state agency overseeing Rhode Island’s services for adults with developmental disabilities is asking for a $20 minimum hourly wage for direct care workers, effective July 1.

The hike was ordered by a federal judge in 2021 to go into effect by 2024, causing consternation in the General Assembly at the time. More recently, outside consultants concurred with the minimum $20 rate.

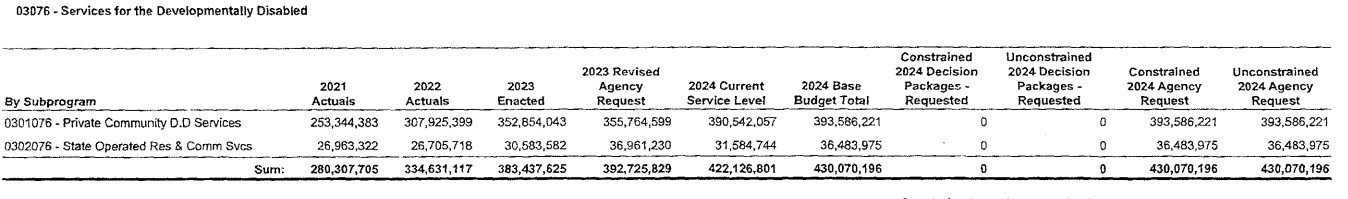

The request is part of an overall $430.1 million budget proposal for developmental disabilities that the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) has submitted to Governor Dan McKee.

McKee is to submit his spending and revenue plan for the state to the General Assembly on Jan. 19.

The BHDDH request for developmental disabilities would add $9.3 million to the current budget of $383.4 million to close a budget deficit in the current fiscal year, ending June 30. About $6 million of the shortfall comes from a state-operated network of group homes.

An additional $37.4 million would be needed to reach total funding of $430.1 million for developmental disabilities in the next fiscal year, beginning July 1.

Spending on developmental disabilities makes up nearly two thirds of the entire BHDDH budget, which is currently $597.1 million. For the next fiscal year, BHDDH is seeking nearly $621.4 million, an increase of of about $24.3 million.

Slightly less than half of BHDDH’s operating revenue comes from state tax dollars, with the rest funded by federal Medicaid money. The overall figures also include some other miscellaneous funding sources.

In a cover letter to the governor in November, BHDDH director Richard Charest said the “Division of Developmental Disabilities continues its commitment in complying with the terms of the 2014 federal consent decree and providing integrated employment and day services.”

A series of substantial wage increases is intended to help stem a worker shortage that prevents eligible adults from gaining access to services to which they are entitled, particularly during the the recovery from the COVID-19 lockdown.

Under pressure from the U.S. District Court, which oversees the consent decree, the General Assembly increased hourly wages from $13.18 to $15.75 in 2021, and then to the current $18.00, which became effective July 1, 2022.

Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. ordered state to hit $20 an hour by 2024. And the outside rate reviewers included the $20 minimum wage in preliminary recommendations made public last September. They also recommend a minimum rate of $22.14 in the fiscal year that would begin July 1, 2024.

As much as the state has been criticized by providers, advocates, and consumers and their families during the last decade for underfunding developmental disabilities, adding more money will not solve all the compliance problems the state has with the consent decree.

Since 2014, the Department of Justice and the federal court system have sought to oversee a cultural shift in the delivery of services which will enable adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities to live regular lives in their communities, exercising choice about where they work and spend leisure time.

In a hearing in U.S. District Court in December, a lawyer for the Department of Justice said the state appeared unlikely to meet a deadline in mid-2024 for full compliance with the consent decree. Amy Romero of the U.S. Attorney’s office in Rhode Island expressed concern about a lack of individualization or “person-centered-ness,” and inadequate accessibility to services in a number of categories, including supports for teenagers making the transition to adulthood.

Romero’s criticism, as well as that of an independent court monitor, stemmed only partly from a chronic shortage of underpaid direct care workers who make up the front line of consent decree compliance.

How the state spends the money, including the degree to which services are individualized, is entwined in the rate review by outside consultants that has been underway for nearly a year. The rate review – itself court-ordered – has not yet been finalized. It covers not only the reimbursement rates to private service providers but the state administrative structures governing the spending.

Preliminary recommendations from the consultants indicated the state wants to continue the existing fee-for-service system, now 11 years old, with many of the same administrative features, including billing for daytime services in 15-minute units and a relatively limited number of individual funding options.

One big change is a proposal to make job-related supports available to all adults with developmental disabilities as an add-on to basic individual budgets.

Officials are working to finish the rate review by the end of January, according to a newsletter of the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) issued Jan. 13.

In the same newsletter, DDD announced that it will advertise eight new positions to help the state fully comply with the consent decree by mid-2024.

The expanded staff will “assist the Division in developing improved communication with the I/DD community and stakeholders, increasing our training capabilities, and enhancing our support for community access and the self-direction population.” (The self-directed population includes individuals and families who design their own programs – roughly a quarter of the caseload of about 4,000 individuals eligible for services.)

The newsletter offered no additional details about the new positions, nor were any immediately available from BHDDH.

The privately-run developmental disabilities system, which includes the self-directed group and private agencies running group homes and offering daytime services, is currently funded for $352.9 million, with about $173.4 million coming from federal Medicaid reimbursements. BHDDH wants $40.7 million more for the private system from both federal and state Medicaid funds, including about $2.9 million to cover a shortfall in the fiscal year ending June 30.

A parallel network of state-run group homes, currently funded for nearly $30.6 million, would need an increase of about $6 million to balance its budget for the current fiscal year, according to the BHDDH budget request. Funding for fiscal 2024, beginning July 1, would continue at the higher level, about $36.5 million.

The administration of former governor Gina Raimondo had tried to privatize the state group homes, but private operators made it clear they were in no financial position to take on the responsibility for additional residents. The plan also faced opposition from unionized state employees who staff the state system, called Rhode Island Community Living and Support (RICLAS). Governor McKee has made it clear he will continue to support RICLAS.

___

Gina Macris is a career journalist with 43 years’ experience as a reporter for the Providence Journal in Providence, RI. She retired in 2012. During her time at the newspaper, she wrote two series about her first-born son, Michael M. Smith. Both series won prizes from the New England Associated Press News Executives Association. Michael, now in his 30s, appears on the cover page, in front of the Rhode Island State House. *